The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare how many human rights are being affected. This includes the polarisation of income equality which has led many into poverty.

Compared to the previous year, the UK government did not report a huge change in general poverty levels in 2019/2020 but the pandemic has caused many to suffer in what is being called the “newly hungry” – people who were traditionally financially comfortable but who now find themselves struggling.

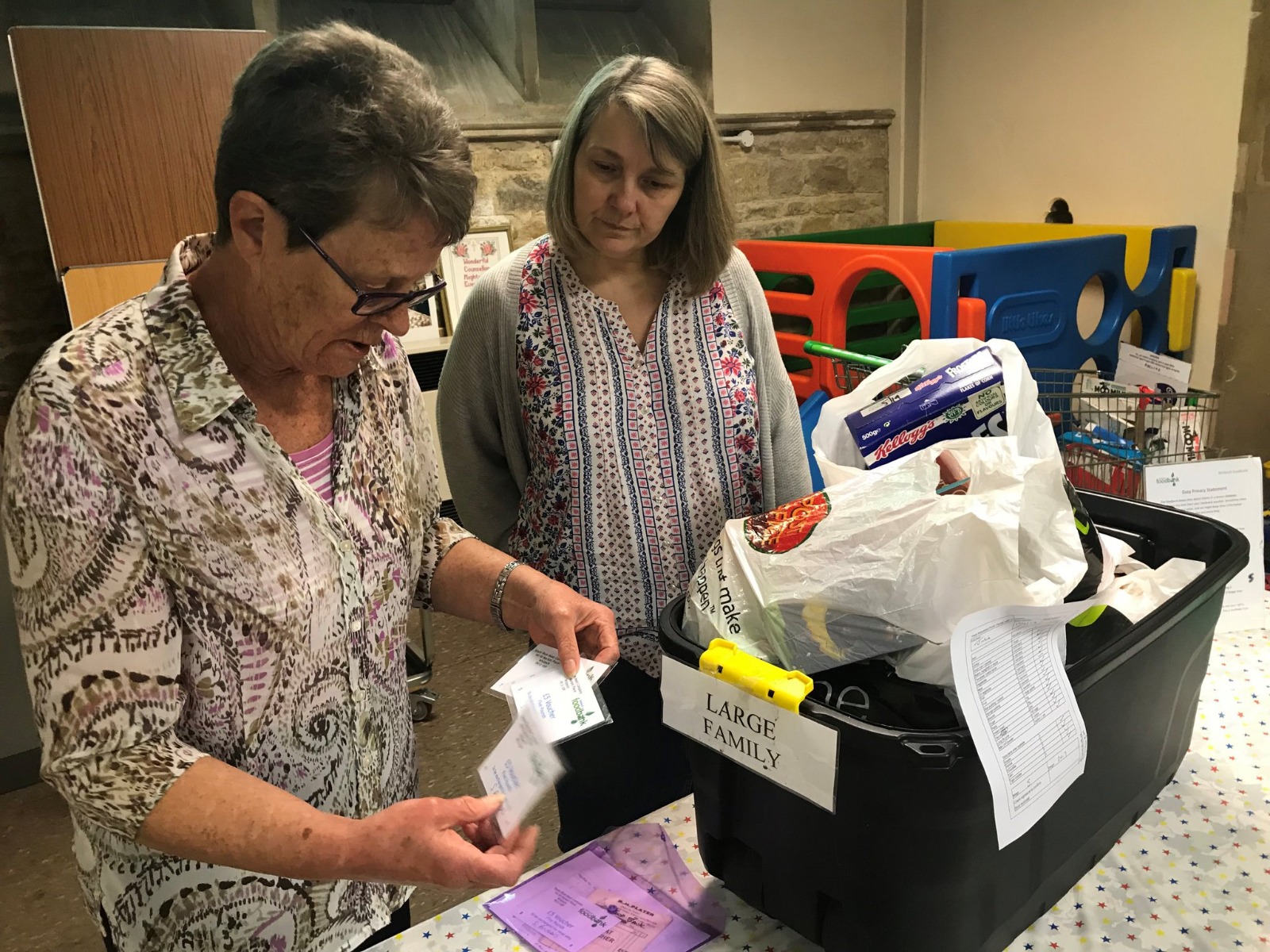

One key indicator of this is an increased dependence on food banks. The Trussell Trust, an NGO and charity which works to end the need for food banks in the UK, reported a 47% increase in three-day emergency food parcels distributed between March and September 2020, compared to the same period in 2019. On both occasions, there was also a marked increase in the number of food parcels going to children.

Independent food banks, of which there were over 900 in February 2021, also increased the amount of emergency parcels they were distributing by 88% between February and October 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. The need for people to rely increasingly on food banks shows the government’s failure in reacting to a severe problem.

Helpers at a food bank in Cambridge. Credit: Kartik Raj

Children have been particularly affected by poverty and the pandemic, with 3.2 million children living in relatively low income (23% of children), an increase from the year before. Food banks have also been important in the transition to online teaching, as many children who relied on free school meals as their main meal of the day could no longer receive it. In turn, this has put more stress on families in poverty to supply five extra meals per week.

Of the first 100 NHS clinical staff to die from the virus, 60 were from marginalised ethnic backgrounds.

Human Rights Watch released a statement on the issue “the [UK] government’s response [to the pandemic and Brexit] highlighted its willingness to set aside human rights for the sake of political expediency and a worrying disdain for the rule of law. Black and Asian people were disproportionately impacted by Covid-19, while growing numbers depended on food banks to get by.”

While the government took steps to strengthen international human rights protection and showed leadership on Belarus and Hong Kong, where were they to take a stand on issues developing at its very front doorstep?

Covid-19 revealed a lot about our world, intensifying weaknesses already present in our systems, no matter how well hidden. While the UK may have found its saviour through the vaccine allowing society a sense of relief, the foundational human rights principles enshrined in law in the UK continues to be weakened.

The pandemic has further demonstrated inequalities in terms of race and ethnicity. Black and Asian people were found to have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, as a study from The Runymede Trust found that out of the first 100 NHS clinical staff to die from the virus, 60 were from marginalised ethnic backgrounds. This is a worrying figure considering that only 20% of NHS staff are from these backgrounds.

Another study at the Barts Health NHS Trust found that Black and Asian patients were, respectively, 30% and 49% more likely to die within 30 days of hospital admission compared to patients from white backgrounds of a similar age and baseline health. Black and Asian patients were also, at 80% and 54% respectively, more likely to be admitted to intensive care and need invasive mechanical ventilation.

The significance of human rights violations in the UK should not be taken away, no matter how they compare to levels in other countries. The institutional racism present in the UK, along with the treatment of asylum seekers and protest clampdowns with the evolution of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill infringing on the freedom of assembly and association, leads the UK down a dangerous path.

It is important, of course, to intervene and discuss violations occurring around the world, but most importantly, they must be discussed at our front doorstep to prevent further escalation. With research acting as a key force of advocacy, the government should take this into account, as well as the voices of those marginalised, to enforce policies that promote inclusivity instead of obstructing it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.