The UK government has taken measures to ensure that “no child should go hungry” after schools were closed indefinitely to slow the spread of Covid-19. But there is still a large bracket of children living in poverty who cannot access support, writes Imogen Richmond-Bishop.

On Tuesday (31 March), education secretary Gavin Williamson unveiled a new scheme aimed at tackling child hunger amid the coronavirus pandemic. Children eligible for free school meals will receive a weekly shopping voucher worth £15 to spend in supermarkets while schools remain closed.

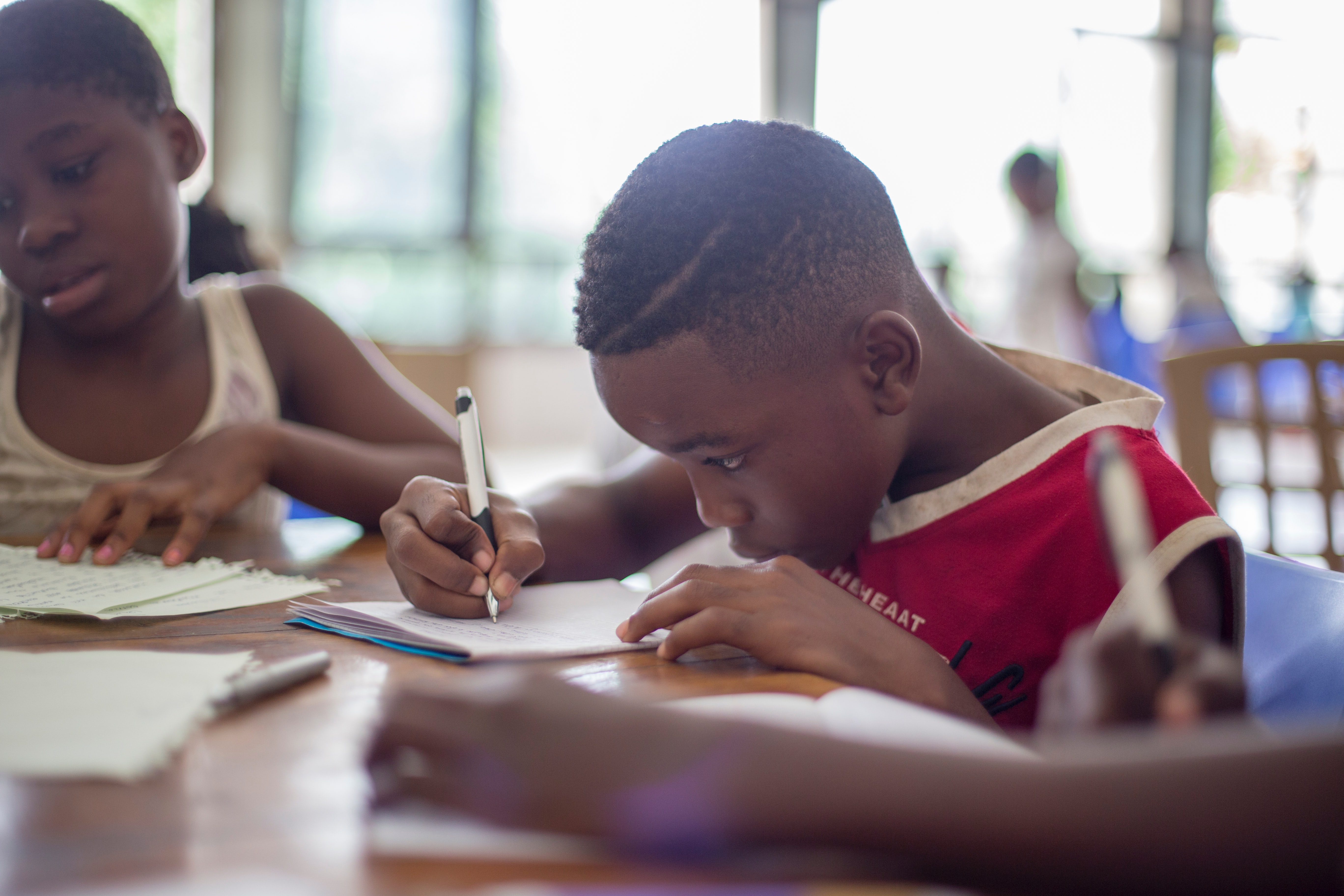

For many children across the country, their school lunch may have been the only hot meal they ate each day. Yet far too many children, despite living in poverty, are unable to receive free school meals due to restrictive eligibility requirements.

Figures analysed by charity Sustain reveal that less than half of the 400,000 children in London who have low food security are getting free school meals.

Children who are not eligible for free school meals include those whose families have no recourse to public funds, as well as those who are no longer entitled due to changes in the eligibility criteria. For these families, no matter the level of financial hardship they face, they cannot automatically access free school meals past the universal entitlement period.

The children who are excluded from this scheme are being penalised for a situation that is outside of their control, as many families who are facing financial difficulties are missing out on much-needed support.

Among the children missing will be those from households who have experienced a drop in earnings due to the economic impact of Covid-19.

Image Credit: Wokandapix/Pixabay

Image Credit: Wokandapix/Pixabay

Destitute families with no recourse to public funds have no welfare safety net to fall back on. School closures and other preventative measures are likely to put additional strain on families who are already facing extreme poverty.

Eve Dickson

Sustain, the Food Foundation and many other charities wrote to numerous ministers across government ahead of the school closures asking for reassurances that all children in need will be supported.

After the schools were closed Kate Osamor MP, who chairs a cross-party group on NRPF, wrote to the education secretary asking for assurances children affected by NRPF would be supported.

Despite these letters and growing levels of concern within civil society, there is still no commitment from the government to ensure that no child goes hungry regardless of immigration status.

Children with NRPF are from some of the most vulnerable households, due to their exclusion from the welfare safety net, which means their parents cannot access any benefits such as Universal Credit.

Eve Dickson, of charity Project 17, said: “Destitute families with no recourse to public funds have no welfare safety net to fall back on. School closures and other preventative measures are likely to put additional strain on families who are already facing extreme poverty.

“Support networks will be more quickly exhausted, single parents may be unable to work, and supporting organisations may close or be at reduced capacity. As a result, there will be an increase in homelessness, hunger and health issues amongst these families.”

People with this immigration condition often rely on food aid, charities, friends and faith groups to keep food on the table. There have been reports that some of these services have been struggling amid the Covid-19 outbreak.

Hunger in childhood is not just a deficit of calories, it is part of a broader denial of rights. For children, household food insecurity can lead to lower educational outcomes, as well as both short-term and long-term physical and mental health consequences.

The government should be using its maximum available resources in order to ensure that all children are able to access a nutritious and dignified diet, and this is even more the case in times of national crisis.

For households struggling to afford food, it is clear that they will likely be facing other financial difficulties, such as struggling to afford electricity and internet bills now that school classes have moved online.

This situation will be even more difficult for families in shared and temporary accommodation, where the living conditions make it impossible for them to self-isolate as well as for children to study and stay healthy.

Lives unbearable before this crisis. Are unimaginable now. "Cockroaches are parading the room as well as climbing our bodies day and night. We can't fumigate the room cos of my baby's health. We're in a terrible and helpless situation."

— The Magpie Project (@magpieprojectuk) March 28, 2020

Cash transfers: A solution

When he unveiled the government’s voucher scheme on Tuesday, Williamson said: “No child should go hungry as a result of the measures introduced to keep people at home, protect the NHS and save lives.”

If the education secretary is serious in his commitment to ensure that no child goes hungry as a result of Covid-19, he should consider the most effective and dignified way of ensuring families have the food they need – cash transfers.

It should go without saying that this support should be open to all those in need, regardless of immigration status.

Food is not just about calories and taste – it’s also about where the food comes from. A tin of beans might have the same nutritional value whether it comes from a food bank or a supermarket, but it does not have the same emotional toll.

Credit: Unsplash

Where people choose to shop is deeply personal. For some it might be the Turkish corner shop that stocks the right type of rice, for others it might be the fruit and veg stall at the market, or a local supermarket. For many, it will be a combination of retailers that will allow a household to find the ingredients they need at the prices they can afford.

Food is also not just about the ingredients. It’s also about the electricity used to keep the fridge running to keep food stored safely, the gas used to cook it, and the bus fare to get to the shops in the first place.

Cash transfers would allow families to procure the food items that will allow their households to stay at home and follow social distancing guidelines.

Food insecurity is not just an issue that has appeared along with Covid-19 – it has been here for years. Any response to Covid-19 to support households in need should be a part of a long-term effort to ensure that living costs do not outstrip wages and welfare payments, and that no one is left destitute.

This should also be done by suspending the NRPF condition that is clearly causing destitution for many across the country, as the Mayor of London has urged the prime minister to do on Monday.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.