When Queen Elizabeth II came to the throne in 1952, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) – the first international expression of fundamental human rights for all – had been adopted by the United Nations General Assembly a mere four years earlier. The European Convention on Human Rights, which protects human rights in law, came into force in the UK a year after the Queen’s coronation.

During the Queen’s 70-year reign, the UK has experienced significant social transformation sparked by social movements calling for rights and freedoms – from Black civil rights to lesbian, gay, bi and trans (LGBTQ+) rights. Though most people support human rights, their application in the UK remains a significant source of contention.

International human rights

Elizabeth II took the crown when Britain presided over an empire, though decolonisation was already underway and the Commonwealth had been established. The monarchy has been much criticised as a symbol of British colonial power. Through the empire, the British government was responsible for gross human rights violations in colonies, which have led to calls for reparations and better education in schools about Britain’s colonial past.

The young Queen took the crown as global powers were building the architecture of human rights in response to the horrors of the Second World War. The UDHR, which the UK helped to draft, articulated universal freedoms and rights for individuals to live their lives freely, equally and in dignity, building on the UN Charter, the UN’s founding document.

It set out the right to life, prohibitions on slavery and torture, the right to a fair trial, and the rights to private and family life. Though not legally binding, the declaration became the basis for international human rights law.

In 2010, speaking at the UN, the Queen said: “I have [also] witnessed great change […] But also, many important things have not changed. The aims and values which inspire the United Nations Charter endure: to promote international peace, security and justice; to relieve and remove the blight of hunger, poverty and disease; and to protect the rights and liberties of every citizen.”

The declaration underlined the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), established by the newly formed Council of Europe in 1951. British politicians helped write the ECHR, which was supported by then prime minister Winston Churchill. Though the UK both joined and left the European Union during the Queen’s reign, the ECHR is separate from the EU.

Speaking at the Council of Europe in 1992, the Queen called the ECHR “so much a part of our democratic heritage”. Six years later, the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) incorporated ECHR rights into UK domestic law, including the rights to freedom of expression, a fair trial and freedom from inhuman or degrading treatment. This meant that anyone whose human rights were breached could take their case to a UK court, rather than having to seek justice at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in Strasbourg.

Though Boris Johnson’s government planned to replace the HRA with a Bill of Rights, plans have been put on hold for now. However, new home secretary Suella Braverman wrote in July during her unsuccessful campaign to become leader of the Conservative party that the UK should leave the ECHR, pointing to its role in blocking the UK’s deportation flights to Rwanda. Prime Minister Liz Truss has refused to rule out such a move.

In June, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees said that the government’s Rwanda plan amounted to a violation of the UN Refugee Convention, which came into force the year before the Queen’s accession. The convention asserts that a refugee should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom, such as LGBTIQ+ people who may be denied access to asylum procedures in Rwanda.

Black civil rights

Following campaigning from Britain’s Black power movement in the UK and the 1958 Notting Hill riots, Parliament passed the Race Relations Act 1968. The Act, a landmark anti-discrimination law, made it illegal to refuse housing, public services or employment on the grounds of race or ethnicity. But the Act was followed by a series of anti-immigration legislation which made it harder for people from Commonwealth countries to get British citizenship.

Legislation guarding against racial discrimination was updated through the Race Relations Act 1976, which established the Commission for Racial Equality, and the Race Relations Act 2000. Under the 2010 Equality Act, it is unlawful to discriminate against a person on the basis of race, nationality or ethnicity.

In 1981, following a long campaign by activists, the “sus” laws were scrapped. This referred to Section 4 of the 1824 Vagrancy Act, which gave police officers discretionary powers to arrest anyone they suspected of loitering, which campaigners say affected a disproportionate number of young Black men. However, to this day, Black people are nine times more likely to face stop and search action from the police.

Women’s liberation and Black women’s movements

All women had been given the right to vote more than 20 years before the Queen ascended to the throne. After the Second World War, the UN Commission on the Status of Women was founded to promote gender equality. However, Britain in the 1950s was still staunchly patriarchal, with restrictive gender roles. Though some equality legislation was passed in Parliament, everything a woman owned or earned became her husband’s property after marriage.

By the 1960s, the women’s liberation movement had started to take shape. The decade saw a step-change in women’s rights, from the 1964 reform of the Married Women’s Property Act to the 1967 Abortion Act, which gave women in Britain the right to abortion in certain circumstances.

The National Women’s Liberation Conference in 1970 galvanised second-wave feminism throughout the 1970s. Women called for equal pay, equal educational opportunities, free contraception and abortion and 24-hour nurseries. Parliament passed the 1970 Equal Pay Act and the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act, which made it illegal to discriminate against women in work, education and training. Despite this, more than 40 years on, the gender pay gap in the UK is still 7.9%.

The Brixton Black Women’s Group was launched in 1973 to fight both racism and sexism, focusing on issues like housing and immigration. Later in the decade, the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent campaigned against deportation policies, domestic violence and reproductive rights, alongside Southall Black Sisters, which continues to campaign to support Black and minority women who have experienced domestic violence. To this day, Black women are still more likely to die in childbirth and are the least likely to be among the UK’s top earners.

While significant progress was made in the 1970s, it was not until 1986 that statutory maternity pay was introduced and rape within marriage was not outlawed until 1994. In the last five years, there has significant progress on women’s rights legislation – from the criminalisation of coercive control to the right to an abortion in Northern Ireland. However, domestic violence and sexual assault continues to disproportionately affect women, while women continue to have lower incomes than men.

LGBTQI+ rights

When the Queen was crowned, male homosexuality was illegal in the UK. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, groups like the Homosexual Law Reform Society campaigned to legalise homosexuality. Though there was no legislation explicitly outlawing lesbian relationships, it was not accepted in society. The first lesbian society, the Minorities Research Group, was founded in 1963, and three years later, the UK’s first trans group, the Beaumont Society. was launched.

Under 1967 Sexual Offences Act, sex between two men was legalised for those over the age of 21 and in private. It was banned in Scotland and Northern Ireland until the 1980s and the age of consent for gay men was lowered to 16 across the UK in 2000.

Throughout the 1970s, groups like the Campaign for Homosexual Equality and the Gay Liberation Front campaigned for LGBT rights. However, the Nullity of Marriage Act 1971 explicitly banned marriages between same-sex couples in England and Wales. It was not until 2013 that it was fully overturned.

Stonewall UK was formed in response to Section 28, part of the 1988 Local Government Act which stipulated that local councils and schools could not ‘promote homosexuality’. Section 28 sparked nationwide protests. The legislation was repealed in Scotland in 2000 and the rest of the UK in 2003.

In the landmark case of Christine Goodwin, who was born a man but identified as a woman, the ECHR found that the law, which did not legislate for gender reassignment, interfered with Goodwin’s private life and breached her right to marry. It paved the way for the 2004 Gender Recognition Act, which allows people to legally change their gender.

The future of human rights

The last 70 years has seen significant progress on human rights in the UK. The Human Rights Act and the Equality Act underline our human rights and ensure we should not be discriminated against because of our religion, age, sex and other ‘protected characteristics’.

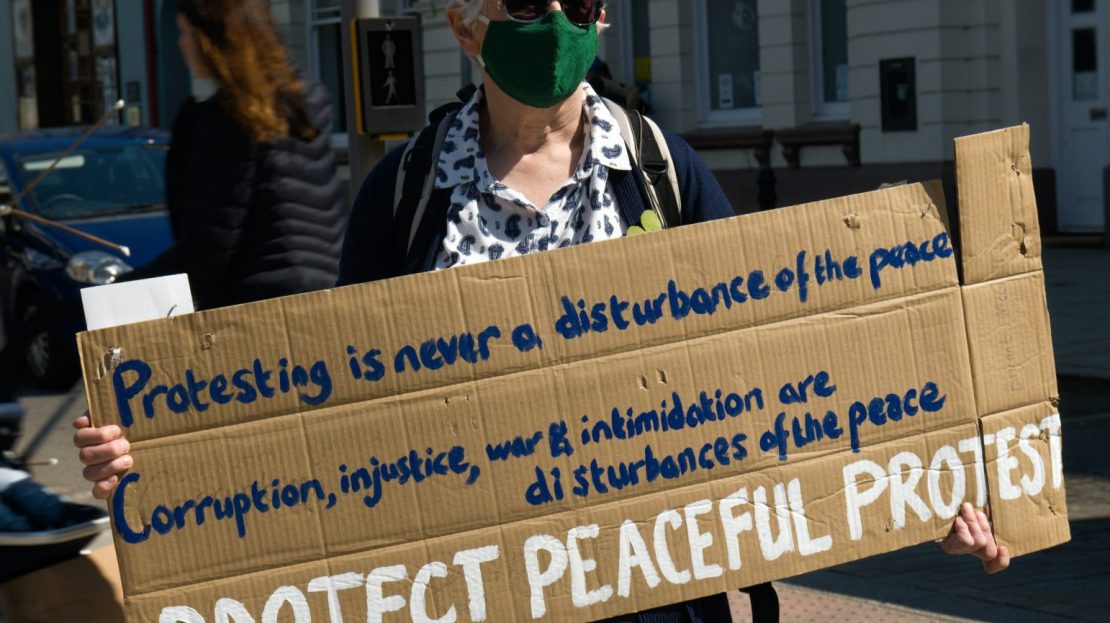

But there are still significant challenges, from workers’ rights to disability rights and migrant rights. Human rights in the UK have been hard won and should never be taken for granted.