As this year’s Black History Month comes to a close, we reflect on some of the civil rights leaders who fought for racial equality here in the UK.

Although countless people recall learning about Martin Luther King Jr’s famed “I have a dream” speech and the long fight for civil rights in the USA, fewer are familiar with the stories of the UK’s own journey towards racial equality.

By the early 18th century, civil liberties were edging into law for working-class people, but for the estimated 14,000 Black people living in Britain, it took until 1833 for slavery to be banned across the British Empire. And it wasn’t until 1965 that Black people’s civil liberties were enshrined in law in the Race Relations Act.

During the Second World War, there was an influx of men from the West Indies who had volunteered to fight alongside the British. After the war, the British government invited workers from the Caribbean to help fill employment gaps in the workforce. But in response to the growing multiculturalism in the country, racial violence increased in cities, like Nottingham and Birmingham.

Facing down discrimination before it was made illegal in Britain, we share here the stories of seven civil rights leaders who took on racism in the UK and fought for equality and human rights long before hashtags could bolster a campaign.

Paul Stephenson

Credit: Wikimedia

In 1963, Stephenson took on a Bristol bus company which refused to employ Black or Asian people. The then 26-year-old teacher organised a 60-day boycott of the city’s buses. After his campaign hit the headlines, thousands of people supported the boycott, and by the end of August 1963, the company had removed the ban.

Stephenson made the headlines again when he appeared in court after he refused to leave a public house after a bar manager protested his being served. He reportedly told Stephenson: “We don’t want you black people in here.” He was subsequently arrested and charged with failing to leave a licensed premises. When witnesses refuted claims that he had acted aggressively, the case against him was dismissed.

Stephenson, who was born in Rochford, Essex, went on to work for the Commission for Racial Equality in London. Later, in 1975, while working on the Sports Council, he campaigned against maintaining sporting contacts with South Africa which was still upholding apartheid. In 1992, he set up the Bristol Black Archives partnership to “protect and promote the history of African-Caribbean people in Bristol”. Awarded an OBE in 2009, campaigners called for a statue of Stephenson, who is now 84, to replace the one toppled by protesters of slave trader Edward Colson in central Bristol in June 2020. A few months later, Great Western Railway named a train in Stephenson’s honour at Bristol Temple Meads station.

Altheia Jones-LeCointe

Credit: Wikimedia

A Trinidadian physician and research scientist, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, 76, is most well-known for her role as a leader of the British Black Panther Movement. She joined in the 1960s when she was studying in London and became involved in activism and the ongoing fight against racism.

She recruited thousands of people, including the late broadcaster and campaigner, Darcus Howe (see below), as well as giving talks in schools and teaching classes in anti-colonialism. One of Jones-LeCointe’s most significant achievements was her protection of Black women and girls in the movement. She built structures within the organisation to ensure men suspected of abuse or exploitation were interrogated and punished if found guilty.

Although Jones-LeCointe insisted the British Black Panther movement had a “collective leadership”, many considered her to be the leader. She received national attention as one of nine protesters, known as The Mangrove Nine, who were arrested and tried after they demonstrated against repeated police raids at The Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill. An estimated 150 people took part in the protest on 9 August 1970 but they were flanked by a reported 200 to 700 police officers. Jones-LeCointe, who represented herself at the trial, used her closing speech to speak about racism in the Metropolitan Police. The jury found the defendants not guilty of conspiracy to incite a riot, which marked a turning point in the fight to recognise and remedy systemic racism in British institutions.

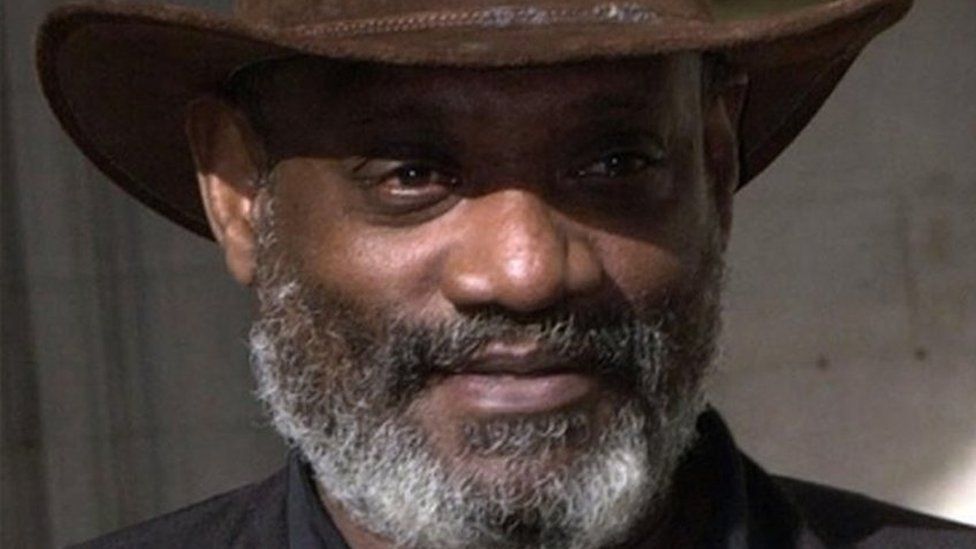

Darcus Howe

Credit: BBC

Darcus Howe – born Leighton Rhett Radford Howe – was a broadcaster and racial justice campaigner. After he arrived in England from Trinidad in 1961, Howe joined the British Black Panthers and was also, like Jones-LeCointe, one of the Mangrove Nine.

During the Mangrove Nine’s trial, Howe elected to represent himself and advocated for an all-black jury, a request that was denied. Following the trial, Howe established the Race Today Collective and was the editor of the Race Today magazine between 1973 and 1985. The magazine supported campaigns in Britain and abroad, which included a strike over poor pay and conditions by female Asian workers at Grunwick Film Processing Laboratory in north-west London in 1976.

Race Today also highlighted the New Cross fire in south-east London in 1981, which resulted in the deaths of 13 young Black people after a suspected racist attack. Howe helped organise the largest ever demonstration by Black people in Britain to protest the government’s indifference to the tragedy – more than 20,000 people marched through London. But what followed was an escalation of stop and search powers by police, called “Operation Swamp 81”, as they attempted to reassert control over London’s Black community. After the subsequent Brixton riots, Howe advocated for Black people to confront white power head-on, something he did for the rest of his life as a journalist, political organiser and activist.

Howe was also involved in the Notting Hill Carnival for many years. He was the Chair of the Carnival Development Committee and participated in the celebration with his steel band the Renegades. He died in London in 2017, aged 74.

Jocelyn Barrow

Credit: Wikimedia

A civil rights activist, Jocelyn Barrow played a key role in lobbying for race relations legislation between 1964 and 1967. A founding member, and later vice-chair, of Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD), which was largely responsible for the Race Relations Act of 1968, Barrow fought for the civil liberties of Black citizens.

Barrow, who was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1929, was an active member of the People’s National Movement on her home island and continued her activism after moving to London in 1959. Alongside her work with CARD, Barrow was a prominent member of the North London West Indian Association (NLWIA), an organisation founded following the Notting Hill riots in 1958, and held numerous other roles in human rights and community relations organisations. Barrow also worked full-time as a teacher and pioneered the introduction of multi-cultural education, highlighting a need for teaching that considered the needs of the various ethnic groups in the UK.

In the 1980s, Barrow became the first black woman appointed as a governor of the BBC. She was also responsible for founding and acting as deputy chair of Ofcom’s predecessor, the Broadcasting Standards Council. Throughout the rest of her life, Barrow was involved in establishing and overseeing museums and she was the first patron of the Black Cultural Archives.

In recognition of her work, she was awarded an OBE in 1972 and in 1992 she became the first black “Dame”. She was appointed a DBE in recognition of her broadcasting and contributions to the European Union while acting as the UK member of the Economic and Social Committee. Barrow died in London in 2020, aged 90.

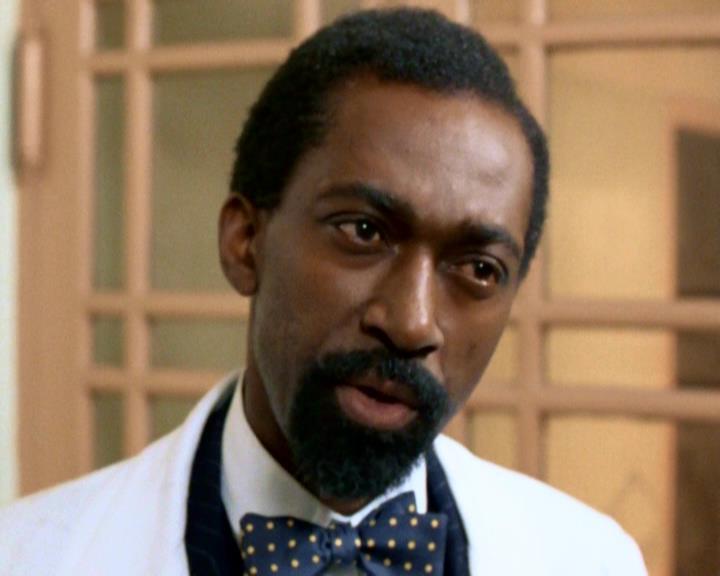

Louis Mahoney

Credit: IMDB

A Gambian-born British actor, Louis Mahoney was an anti-racist activist and campaigner for racial equality in acting. Initially focused on a career as a doctor, Mahoney decided to pursue his ambition to become an actor. He attended the Royal (then Central) School of Speech and Drama in the 1960s and later was one of the first Black actors to join the Royal Shakespeare Company. He regularly worked on some of Britain’s most famous stages, including the Young Vic and the National Theatre.

Barrow forged a successful career as an actor at a time when Black performers were frequently sidelined or stereotyped. He often appeared on screen, too, including in British classics, like Doctor Who, Miss Marple and Fawlty Towers.

But he was also a long-standing campaigner for racial equality within the acting industry. In 1976, he co-created the Black Theatre Workshop and volunteered his time to help disadvantaged young Black people. A few years later he helped to found Performers Against Racism in protest at apartheid in South Africa. He also represented African and Asian members as joint vice-president of the actors’ union Equity between 1994 and 1996.

After a 55-year career, Mahoney’s final performance was in the BBC’s divorce drama The Split. He died in London in 2020, aged 81.

Olive Morris

Credit: Flickr

Olive Morris was just 27 when she died, but she was widely commemorated as a powerful campaigner for racial and gender equality, squatters’ rights and housing. The Jamaican-born community activist co-founded the Brixton Black Women’s Group in 1973. The organisation later successfully campaigned to have 18 Brixton Hill in south London renamed Olive Morris House as a memorial to her. Morris was also a key member of the British Black Panther Movement from 1968.

Morris’ activism started young. When she was about 17, she tried to stop police officers arresting a Nigerian diplomat who they suspected of stealing a Mercedes car, which was his. Morris was arrested and reportedly beaten by police before she was fined £10 and given a suspended sentence. In the 1970s, she played a key role in campaigning for squatters’ rights.

As a co-founding member of the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent, Morris also worked tirelessly to overcome the struggles endured by Black women. As part of her work, Morris travelled all over the world, including to Morocco, Algeria, Spain and China. A communist and radical Black feminist, Morris committed herself to resisting racial, class and sexual oppression before she died from cancer in 1979.

Mavis Best

Credit: Media Diversified

In the 1970s, activist Mavis Best played a key role in scrapping the infamous Sus law – based on the 1824 Vagrancy Act – which was manipulated by police officers to stop, search, arrest, detain and assault young Black men and women. Alongside a group of Black women from Lewisham, in south-east London, and following a series of demonstrations and meetings, Best successfully lobbied police and government to scrap the Sus law.

Prior to their successful campaign, thousands of young Black people endured police abuse under the Sus law. Before securing repeal of the law completely, Best worked with other Black women to rescue children from police stations by demanding their release. After three years of lobbying with their campaign group Scrap Sus Campaign, Best and her fellow activists succeeded in getting the unfair law changed.