As 2021 draws nearer, EachOther looks back at the first six months of the past year and highlights some of the biggest stories we reported on.

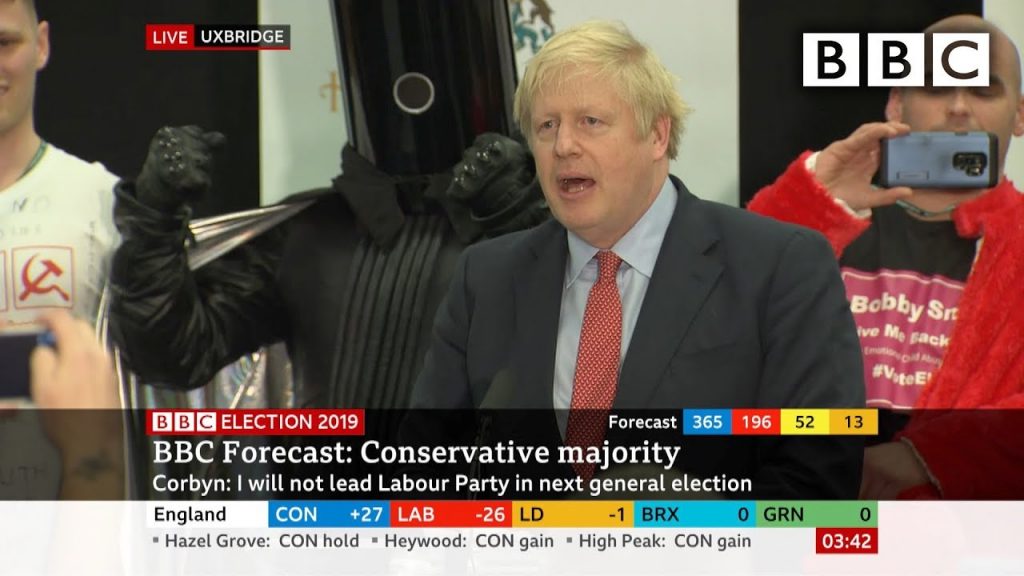

At the start of 2020, a month after the Conservative party’s landslide election victory, we outlined five major human rights trends to watch.

Among them were the Tories’ manifesto pledge to update the Human Rights Act and Judicial Review; the impact of Brexit and future trade deals on workers’ rights; among many others.

Little did we know, at that time, that one issue – the coronavirus pandemic – would come to affect our human rights in profound and unprecedented ways.

Below, we revisit the stories we ran from January to June this year, tracing the development of the pandemic alongside other major human rights issues.

January

Credit: YouTube.

On January 31 at 11pm, Britain formally left the European Union – four years after the 2016 referendum. Things mostly stayed the same as an 11-month transition period began, during which the EU and UK have been negotiating the terms of their future relationship. The most important changes to our rights are due to come into effect after December 2020. We examined them in this story. Time is now running out for the EU and UK to come to a deal.

Among the human rights implications of Brexit is the government’s legal obligations toward unaccompanied child refugees stranded in Europe, which were significantly reduced in Boris Johnson’s Withdrawal Agreement Bill (WAB).

In January, MPs rejected an amendment to the Bill which would have guaranteed lone child refugees’ right to be reunited with their family members in the UK after Brexit.

A petition urging the government to support the amendment gained almost 350,000 signatures.

Meanwhile, on 17 January an open letter was published calling on the government to end its ‘failed’ Prevent policy and its “criminalisation of communities and suppression of civil liberties”.

“Decades of security-heavy policies have not reduced political violence nor addressed the root causes of it. We believe an alternative approach must break from the endless cycle of review, reform and rhetoric.”

The open letter, entitled ‘Towards a Society Beyond Prevent’.

Among the 114 signatories were Magid Magid, a member of European Parliament; UK hip hop artist Lowkey; police monitoring network Netpol; and Professor Humayun Ansari OBE and Remy Mohamed, the president of the Association of Muslim Lawyers.

February

A face mask and hand sanitizer. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Credit: Unsplash

The UK government declares the outbreak of the new coronavirus – believed to have started in Wuhan, China – a “serious and imminent threat to public health”, introducing additional powers to tackle its spread.

As of 11 February, the virus was estimated to have infected over 40,000 people worldwide – with eight confirmed cases in the UK.

In these early days of the pandemic in the UK, we ran a story examining three initial human rights concerns: our right to health; quarantine and our right to liberty; and discrimination and xenophobia that emerged in response to the virus.

In February, the Home Office also unveiled its new ‘points-based’ immigration policy – as promised in the Conservative election manifesto – that would come into effect on 1 January next year.

It would require overseas citizens to reach 70 points to be able to work in the UK. Points are gained based on qualifications, English-speaking ability and skills, among other factors.

Experts and unions warned that the plans to close the UK’s borders to so-called ‘low-skilled’ migrants would worsen staff shortages in the ‘crisis-stricken’ social care system.

The sudden death by suicide of TV presenter Caroline Flack on 15 February triggered intense backlash against the UK’s tabloid press and calls for stricter laws to safeguard the human rights of those in the public eye.

Calls for a “Caroline’s Law” were spearheaded by Hollyoaks actress Stephanie Davis.

Among the campaign’s seven key demands were to prevent the press “invading privacy”; “releasing information that there is no evidence for” or using quotes from an “unreliable source”.

She argues these restrictions would help ensure celebrities’ “mental health and human rights are being respect[ed] appropriately”.

Davis’ proposals are listed in an online petition which has so far gained more than 890,000 signatures.

March

Credit: Unsplash

At the beginning of March, the government unveiled its action plan in response to the coronavirus epidemic. At this point it was becoming clearer that the spread of the virus – and the governments response to it – would impact on more of our rights.

Among them was our right to education – with Boris Johnson eventually ordering all schools to close temporarily on 20 March.

Official NHS guidance in early March encouraged members of the public to wash their hands often and for at least 20 seconds, to increase “social distancing” from others and to “self-isolate” if presenting with symptoms.

But it was clear for those who are in homeless accommodation or sleeping rough, there are obvious obstacles. EachOther spoke to a number of people experiencing homelessness about their concerns in the early days of the pandemic.

Among them was filmmaker Paul Atherton, 51, who has been homeless for more than a decade. He had been spending his nights in Heathrow Terminal 5, drawn to its relative security and 24-hour-a-day food shop. He was one of the more than 283 people who were seen sleeping rough in the airport last year, according to data from the London Mayor’s office.

Atherton has chronic fatigue syndrome, putting him among those group of people most vulnerable to Covid-19. In spite of this, he said: “I am not panicking. I have been homeless for over a decade. I’m expecting to die everyday.”

Social distancing would also prove extremely difficult for the 83,000 people in Britain’s often overcrowded prisons. In March, we examined what measures the government could put in place to protect the rights of people in detention.

On 25 March, the government also gained “unprecedented powers” in its bid to curb the coronavirus pandemic.

The Emergency Coronavirus Act grants police, immigration officers and public health officials new powers to detain “potentially infectious persons” and put them in isolation facilities.

It will also enable the government to prohibit and restrict gatherings and public events for the purpose of curbing the spread of Covid-19.

The 329-page Bill became law on Wednesday (25 March) after passing through Parliament in just three days without opposition MPs forcing any votes and without amendment from the Lords.

It will last for two years but the government agreed that Parliament should debate and vote on the act every six months.

April

Pauline Anderson OBE, chair of the Traveller Movement, has said she is “appalled at the misuse” of her interview in Dispatches: The Truth About Traveller Crime.

Credit: Channel 4

Charities and politicians accused Channel 4 of “sowing division” after it aired its controversial documentary ‘Dispatches: The Truth about Traveller Crime‘ in April.

Campaigners stated that Traveller communities saw “an increase in prejudice” following the broadcast of a controversial Channel 4 documentary.

Meanwhile, we also reported on how the the looming threat of eviction undermined the ability of homeless Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) communities in England to adhere to coronavirus lockdown measures.

Campaigners are urging Westminster to follow the example of the Scottish and Welsh governments by advising local authorities, police and other landowners to halt all evictions of unauthorised sites amid the pandemic, unless there is an immediate threat to public safety.

In terms of workers rights, a report by the Institute of Employment Rights (IER) found that 11 million UK workers could face destitution due to gaps in the government’s coronavirus income protection schemes.

The report added that the UK’s roughly five million gig-economy workers are also unlikely to be eligible for the furlough scheme.

They will instead be able to claim from the government’s Self-Employment Income Protection Scheme – but the report warns this also has gaps.

We also spoke to Richard Ratcliffe, who has spent over four years campaigning for his wife Nazanin’s release from prison in Iran.

It was on 3 April 2016 that former aid worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was arrested by the Revolutionary Guards in Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Airport on her return from visiting her parents with her daughter Gabriella. In April this year, the 41-year-old mum from London had her furlough from prison extended and is being considered for clemency, along with thousands of other prisoners temporarily released to curb the spread of Covid-19 through the country’s jails.

May

On 7 May, Isle of Wight residents became the first to test the NHS Covid-19 contact tracing app before it would be rolled out across the UK.

The app was touted as key to quelling the outbreak and easing lockdown restrictions – but it was estimated that 60% of the UK public would need to use it for this to happen.

We examined whether or not the app “gives reason to be trusted” – which experts said was important to ensure take up. The app would be able to inform you if you had crossed paths with someone who believes they have developed Covid-19 symptoms, and would instruct you to get tested and to self-isolate for up to two weeks.

NHS Test and Trace App. Credit: Unsplash

As the first tragic images of the UK’s coronavirus victims emerged, it quickly became evident the lives being lost were disproportionately those from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) communities. In May, we spoke to BAME key workers about how they felt to be working on the Covid frontlines.

Analysis published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in May revealed that Black people were four times more likely to die after contracting Covid-19 than white people – while people of Bangladeshi and Pakistani, Indian, and mixed ethnicities also have a significantly higher risk of death.

London Mayor Sadiq Khan said it is the “uncomfortable truth” that people from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to live in overcrowded accommodation, and “they are more likely to live in poverty or work in precarious and low-paid jobs”.

With the unprecedented stress and pressure placed upon the NHS, a survey by the British Medical Association (BMA) revealed that 45% of more than 10,000 doctors were struggling with depression, anxiety, stress, burnout or other mental health conditions relating to, or worsened by, the coronavirus crisis.

There was also an increase in calls to the BMA’s wellbeing support service from doctors anxious about going into work to face unknown situations. Others who responded to the survey felt as though they were risking their lives and those of loved ones due to a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE).

The BMA called for “a longterm strategy for protecting and maintaining the physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing” of the NHS’ workforce.

June

Black Lives Matter protest in Washington DC on 6 June 2020. Credit: Unsplash

Following the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed in US police custody, anti-racism protests spread from Minneapolis – his home city – across the globe.

On 3 June, huge crowds could be heard in London’s Hyde Park chanting “I can’t breathe” – the painful last words Floyd uttered as he lay on the ground while a white police officer knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes. We produced an explainer to help protesters know their rights amid the pandemic restrictions in place at the time, and how to stay safe and healthy.

In the same month, charities called for safe and legal routes to claim asylum in France and the UK as the situation in migrant camps in Calais and Dunkirk deteriorated amid the Covid-19 crisis.

Charity Care4Calais told EachOther that French authorities had continued a “harsh” campaign of evictions against the hundreds of people believed to be staying in the camps.

Environmental charity Roots, who are working on the ground in Dunkirk, said that camp dwellers housed in temporary accommodation provided by the authorities have complained of overcrowding and “inedible food”.

Meanwhile, since April more than 1,000 migrants had attempted perilous journeys in small boats across the English Channel only to be intercepted by UK and French authorities.

On 15 June, Border Force vessels blocked five boats carrying 49 men and women from countries including Iraq, Sudan and Syria, according to the BBC.

- Stay tuned for part two of our review of 2020 which will be published later this week.