A campaign group of women affected by the state pension age rise has vowed to continue its fight to secure “full restitution” after losing its case at the appeal court.

About 3.8million 1950s-born women are estimated to have been affected by the government increasing the pension age from 60 to 66 through a series of laws introduced between 1995 and 2014.

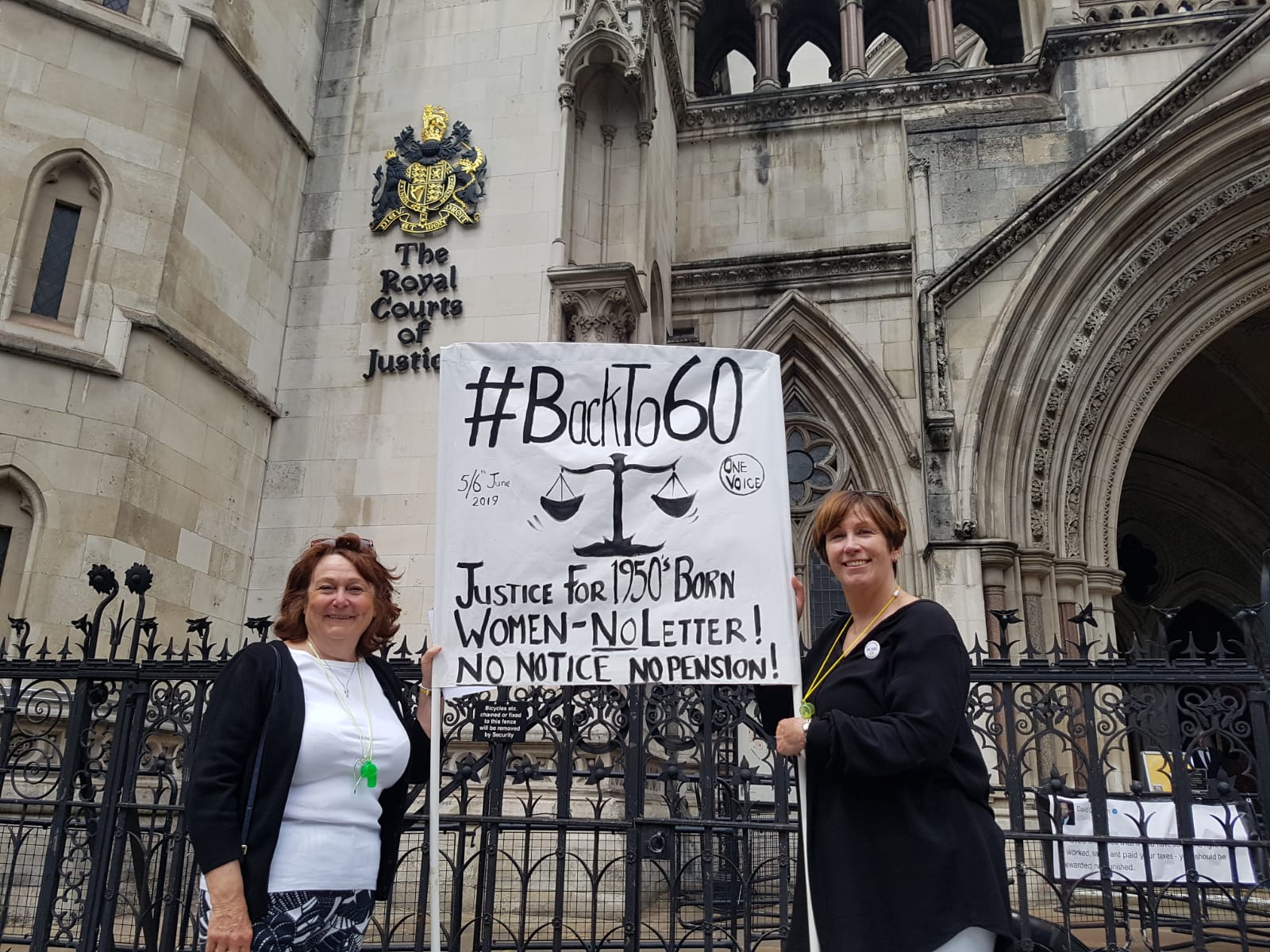

Julie Delve and Karen Glynn, both in their 60s, brought a judicial review against the Department for Work and Pensions (DwP) in June last year arguing the changes were unlawfully discriminatory on the basis of age and sex.

During last year’s hearing, the High Court heard the changes worsened existing inequalities suffered by women of that generation – with some women expected to lose more than £40,000 from their pension, leading them to suffer hardship.

But judges, while “saddened” by the stories they heard, ruled that there was no unlawful discrimination. The change had equalised a “historic asymmetry” in men and women’s pension age, they said.

Delve and Glynn, backed by campaign group BackTo60, took their case to the Court of Appeal – but on Tuesday lost their case.

In a written judgment, Master of the Rolls Sir Terrence Etherton, Lord Justice Underhill and Lady Justice Rose unanimously dismissed the appeal. “Despite the sympathy that we, like the members of the [High Court], feel for the appellants and other women in their position, we are satisfied that this is not a case where the court can interfere with the decisions taken through the parliamentary process,” they said.

In light of the “extensive evidence” submitted by the government, the senior judges added it was “impossible to say that the government’s decision to strike the balance where it did – between the need to put state pension provision on a sustainable footing and the recognition of the hardship that could result for those affected by the changes – was manifestly without reasonable foundation”.

Nevertheless, the ruling does not mark the end of BackTo60’s campaign.

Joanne Welch, BackTo60’s founder and director, told EachOther: “We will not retreat – full restitution is in the crosshairs and we will ensure we capture that for all 50s women. One way or another.”

The group is considering appealing its case to the Supreme Court. It is also pursuing other avenues, such as drafting a women’s Bill of Rights.

“Whichever mechanism we use, nothing has changed. We will get justice, whether by hook or by crook.”

The judicial review was brought by Julie Delve, 62, and Karen Glynn, 63, who were both due to receive their state pensions in 2018 and 2016 respectively. However, following legislative changes, they must now both wait until they are 66.

The High Court heard in June last year that the legislation breached Article 14 of the Human Rights Convention – which guards against discrimination on the basis of age and sex – and was contrary to the general principles of European Union law and the UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (Cedaw).

“Although the objective was equalisation, what has happened is the reverse,” Michael Mansfield QC, who represented one of the claimants, said at the time. “We would argue that it has been the case because it has imposed upon a generation who were already suffering inequality within the workplace which led to disadvantage.”

He added: “They have pushed women already disadvantaged into the lowest percentile you can imagine. They are on the brink of survival.”

In June, 61-year-old mum-of-two Joy Scott, from Great Yarmouth, told EachOther of her fears that she may need to sell her home after being told an increase in her pensionable age from 60 to 66 means she will lose £45,000.

But James Eadie QC, representing the Department of Work and Pensions (DwP), argued there was “no causal link” between the law change and the disadvantages that the women have suffered.

“Those disadvantages, unfortunate as they were, existed before and will exist afterwards.”

Mr Eadie said the purpose of the state pension age is “not a mechanism for correcting ills by other causes.”

In a 43-page judgment published in October last year, Lord Justice Irwin and Justice Whipple dismissed the case at the High Court on all grounds.

It reads: “There was no direct discrimination on grounds of sex, because this legislation does not treat women less favourably than men in law. Rather it equalises a historic asymmetry between men and women and thereby corrects historic direct discrimination against men.”

It also rejected the claimants’ argument that the policy was discriminatory based on age; adding that, even if it was, “it could be justified on the facts”.

The judges did offer the concession that they were “saddened by the stories we read in the evidence lodged by the claimants”.

Nevertheless, their role as judges in this case is limited. “The wider issues raised by the claimants, about whether these choices were right or wrong or good or bad, are not for us,” the judgement added. “They are for members of the public and their elected representatives.”

What next?

Welch confirmed to EachOther that the group is considering taking its case to the Supreme Court.

She added the pensions campaign has “ignited” a larger battle for gender equality, which now seeks to establish a women’s bill of rights in the UK.

“We’ve gone from representing 3.8million [1950s-born] women to half of the country,” she said.

The group has established a grassroots “people’s tribunal”, featuring John Cooper QC, which will examine the UK’s “failure” to enshrine the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (Cedaw) into domestic law.

The UK ratified Cedaw in 1986 but, as it has not been incorporated into UK law, it cannot be used in domestic courts and tribunals.

Described as an international “bill of rights” for women, Cedaw aims to ensure rights are enjoyed equally between men and women.

The treaty also contains a provision which the campaigners believe could help achieve their aim to secure “full restitution” for the almost 4 million women affected by the pension age change.

It allows governments to introduce “temporary special measures” to effect “structural, social and cultural changes necessary to correct past and current forms of discrimination against women”.

It is argued that this could be used to bypass the existing pension legislation to compensate the 1950s-born women.

The grassroots people’s tribunal, which is independent of the UK’s justice system, is set to hold an up to five-day hearing featuring judges and expert academic witnesses. One of its aims is to produce a draft a bill to give Cedaw “full effect” in the UK.

Without being enshrined in UK law, the main way Cedaw is currently enforced is by a committee of 23 experts who write annual reports on countries’ progress in achieving its aims.

BackTo60 said it is also due to submit evidence at Cedaw’s 77th committee, which is set to meet in Geneva next month.

“We are hoping they will implement an investigation [into the UK],” Welch said.

Editor’s Note 14/10/2020: Article amended on September 19 to clarify when the judgment at the High Court is being referred to, as opposed to the Court of Appeal judgment.