While most of the country remains at home to stop the spread of the coronavirus, key workers are keeping the country running at their own personal risk.

Among their ranks include NHS staff, social care workers, police, firefighters, journalists, transport workers, delivery drivers, prison and probation workers and supermarket staff.

Underpaid professions, such as carers and farm workers, that only months ago were referred to as “low-skilled” are now being recognised as indispensable.

Official figures show that the number of people who have died from coronavirus in the UK stands at 26,771. Many of them are key workers, a proportion of them migrants who do not have the option to stay at home because they may not currently be entitled to social security payments.

In spite of these high personal risks, essential workers in some industries earn as little as £9 an hour. Data from the Office of National Statistics has revealed that people in the poorest, most deprived parts of England and Wales are more than twice as likely to die from Covid-19 than those in affluent areas.

An online petition demanding that no key worker earns less than the median salary of £15 an hour has been signed by more than 6,000 people. Another calling on the government to offer support to migrants and other vulnerable people gained more than 20,000 signatures.

EachOther spoke to a range of people in essential jobs to celebrate their work and learn more about how the pandemic has changed working conditions.

Dave Woolley, 55

Former soldier Dave Woolley is a general assistant at a supermarket in Skegness.

Dave currently works as a general assistant at a Skegness supermarket, responsible for everything from keeping shelves stocked to unloading food supplies from delivery lorries.

How is the pandemic affecting his life and work?

“To be fair, things have changed massively,” he said. “I never used to be an anxious person. I am an ex-miner and an ex-soldier. But when I am taking the bus to work everyday, it’s like meeting your girlfriend’s parents for the very first time.”

Where once he was able to laugh and joke with the customers, he now feels that many treat him and his colleagues as an inconvenience.

In one instance, a woman told him he “was not significant enough to listen to” when he asked her to keep within a set of yellow arrows to help customers maintain physical distancing.

But there have also been acts of kindness and solidarity. “The other day a lady brought in six boxes of chocolates and said: ‘Can you make sure everybody gets some of these, because I think you are doing a wonderful job.'”

The father-of-two earns about £9.30 an hour for his work keeping the supermarket in operation. When asked how this will enable him to make ends meet, he said: “It’s a struggle. We’ve got a bit of savings but it’s quite hand to mouth.”

Emily Hawthorn, 20

Emily Hawthorn is a student nurse and works shifts as a healthcare assistant in an A&E ward in Southampton.

Student nurse Emily Hawthorn is working shifts as a healthcare assistant in the A&E ward of a Southampton hospital while she completes her degree.

She currently works in the “blue” zone of the ward, for those patients without Covid-19 symptoms, but must still don protective equipment including masks and gloves.

“You have to work with quite a few elderly people,” she said. “That is the most difficult bit – trying to explain to them why you can’t see people’s faces.”

Asked how she feels to be working on the frontline, she added: “We are all taking the necessary precautions to protect ourselves and our patients.

“But it is difficult coming home to my partner – who is not considered as high risk – and thinking about whether you might pass on the virus.”

This month, Emily is due to start a voluntary placement to help with the pandemic response, and said she is prepared to work wherever she is most needed.

At present, the 20-year-old earns about £9.80 an hour during her shifts.

“It’s definitely hard – especially when it comes to placements,” she said. “It can be hard to just focus on learning.”

Anderson da Silva, 43

Anderson da Silva transports medical samples across London.

Anderson, from Brazil, has been working as a courier transporting medical samples between hospitals across London by motorbike and van for the past eight years.

Many of his colleagues are so-called gig-economy workers – earning in the region of £12 an hour – but Anderson is now a direct employee after taking the company to tribunal two years ago.

“I am proud of my work and being helpful, despite the fact I am taking all this risk,” he told EachOther.

“But I worry about my brother. He has a weak immune system and we live in the same flat together.”

He spoke of having to enter into potentially contagious areas, sometimes delivering items to patients’ bedsides at various hospitals.

He said that, amid a dispute with his employer, he relies on the hospitals he visits to provide him with necessary protective equipment, such as a masks and gloves.

Julie Laking

Credit: Caio Christofoli / Pexels

Julie Laking, from the Philippines, is employed by outsourcing giant Sodexo to work as a cleaner at an east London hospital .

She told EachOther how she felt like running away when the endoscopy ward, where she works, was first made into an intensive care unit as Covid-19 hit the UK.

As many as 25 of the UK’s Filipino health workers have died from the disease, the deputy Philippine ambassador to the UK told Sky News.

“I thought I was brave, but then I came face-to-face with people suffering, and even dying – that’s when I wanted to get out,” she said.

“But you can’t run away from this kind of job. So I said we must accept it, and comply with all the rules.”

Julie said she is one of the lucky ones who has been paid overtime for the whole week. Many of her colleagues have told her they have not been given the extra payment.

She thinks a pay increase is only fair for health service workers on the frontline.

“I wish the government would hear us. We deserve an increase because we are risking our lives.

“I am a Filipino, and there are a lot of us working here. How many of us have given our lives?

“It really angers me, and my heart goes out to everyone working here, especially my fellow Filipinos.”

Julie added that pay is not frontline workers’ only concern – supporting their families is also crucial.

“Our job is a job, but life is life. You cannot pay for life, but I wish they would understand we also have families to look after, rent to pay.

“Please look after us. We have children waiting for us at home.”

Johnie Meharry, 39

Johnie Meharry has been driving buses in north London for the past 15 years. Credit: Supplied

Johnie Meharry has been driving London buses for more than 15 years and continues to do so amid the pandemic.

At least 15 of his colleagues have died, the Mayor of London confirmed last month.

“At the time the pandemic started, it was worrying for everyone,” he said. “But I am still driving my bus every day.

“I have a process that I do at every journey to make sure I am sanitising my hands and make sure not to touch my face.”

He said that cleaning standards in London buses are high at the moment but that more needs to be done to ensure passengers keep to social distancing. “The buses are still filling up,” he said.

Asked how passengers are treating him, he added: “I have never been thanked as much in all my time as a bus driver as I have in the last three or four weeks.”

He said that as he turned into one road in West Hampstead on Wednesday, there were around 15 people standing there and clapping for him.

Claire Carmichael, 36

Claire Carmichael is a nurse at a GP practise in Portsmouth.

Claire Carmichael began working as nurse at a GP practise in Portsmouth in February this year, carrying out blood tests and ECGs among other procedures.

Before the onset of the pandemic, she would see on average 23 patients a day.

This has dropped to about 12 people a day, as the public have been advised to avoid going to the GP if they develop Covid-19 symptoms so as not to pass on the virus.

The practice has introduced ten-minute slots between appointments to clean and disinfect everything.

She told EachOther that she feels fortunate that her practice currently has sufficient quantities of personal protective equipment as she hears stories of the difficult situations her friends are facing as they work in hospitals around the country.

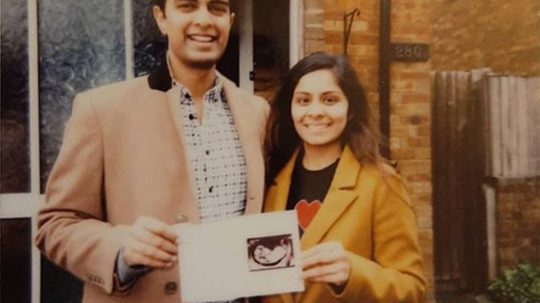

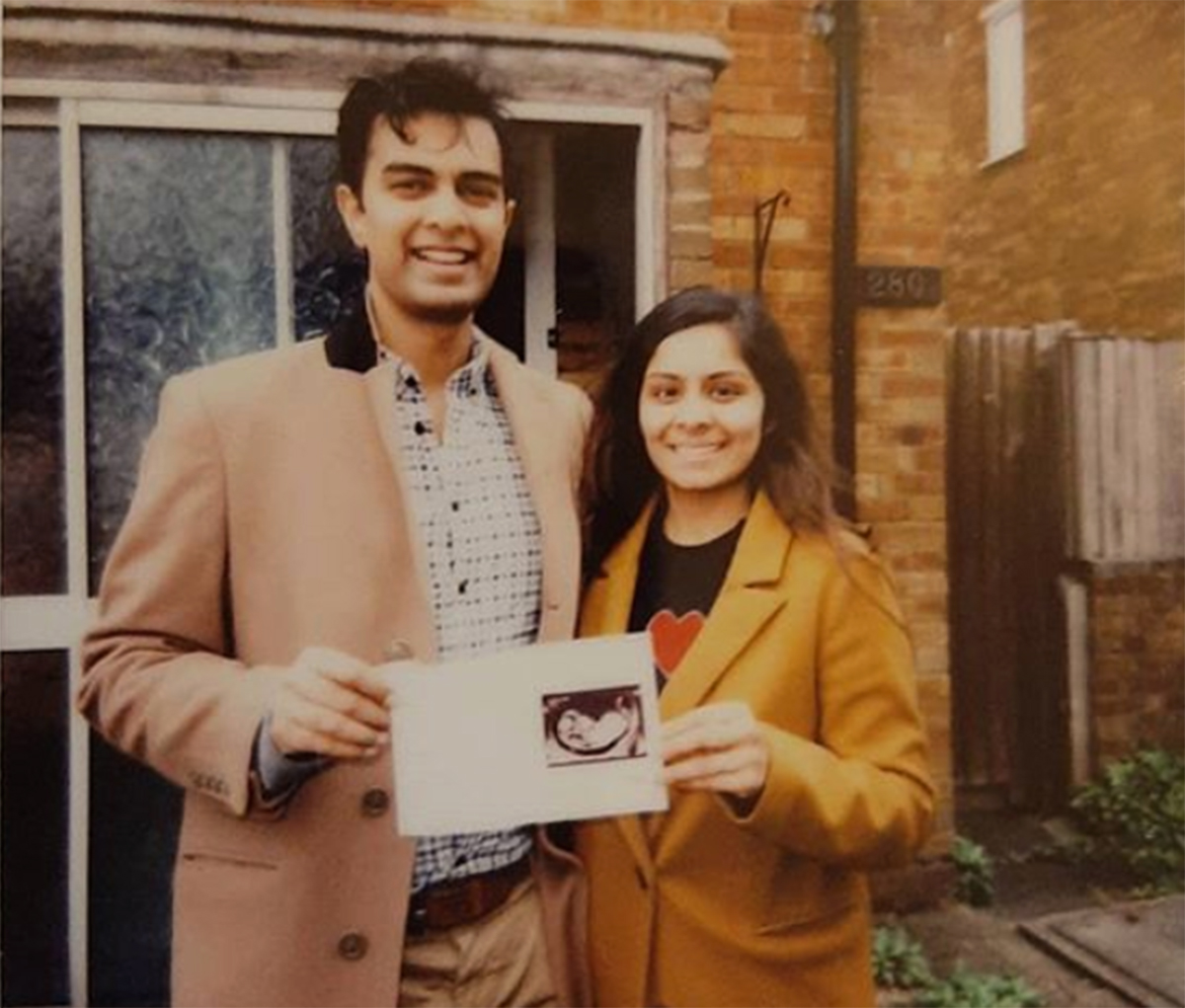

Dr Nishant Joshi and Dr Meenal Viz

Married couple Dr Nishant Joshi and Dr Meenal Viz. Credit: Supplied

Dr Meenal Viz, a hospital doctor who is nearly 7 months pregnant, was working in a hospital exposed to Covid-19 patients up until recently, before moving to an office-based role.

Her husband, Dr Nishant Joshi, who was among the first doctors to speak out over PPE shortages, continues to work in a Luton hospital’s A&E ward.

In March, Joshi told EachOther that while his own hospital has received shipments of equipment, dozens of colleagues in hospitals across the country remain lacking.

“I do believe it’s negligence on the government’s behalf to have not protected us,” he said. “The whole point of PPE is it is supposed to be protective and preventive… we are now seeing unprecedented levels of staff sickness.”

He spoke of instances where junior nurses with poor experience of handling ventilators are having to manage several patients by themselves in an Intensive Care Unit as a consequence of staff shortages.

“We need the government to protect us on a daily basis – and not just in a pandemic when you need us,” he added.

On Thursday (23 April), the couple launched a legal challenge against the government’s guidance on personal protective equipment (PPE), which they argue exposes them to coronavirus infections.