The discussion around diversity and racism in Britain’s traditional media outlets has been reinvigorated by the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement. But less talked about is how Black Britons have for decades forged their own independent media platforms to serve their communities where the mainstream was found wanting. EachOther asks a range of journalists why Black media continues to be needed in 2020.

The Voice – ‘Britain’s leading Black national newspaper’ – marked its 38th anniversary on Sunday.

Founded in 1982, a year after UK racial tensions were brought to the fore in the Brixton uprising, Jamaican-born Briton Val McCalla founded the semi-tabloid-style newspaper in part to address racism.

The paper, like others, has had its share of controversies. But it has also been a training ground for countless leading Black British journalists at more mainstream outlets.

Among them is Rageh Omaar, formerly of the BBC and now ITV, and the Huffington Post’s investigative journalist Nadine White.

There is scant data on what proportion of British journalists were from minority ethnic backgrounds back in 1982. But the picture today remains far from representative.

In 2017, the National Council for the Training of Journalists found in a report that around 94% of journalists are white, despite BAME people making up 14% of the population. Meanwhile, only about 0.2% of British journalists are black, compared to 3% of our country’s population, according to a 2016 study from the Reuters Institute.

Last Monday, the prominent British broadcaster David Olusoga said racism in the media industry had driven out a “lost generation” of Black talent during his keynote speech at the Edinburgh television festival. Days later the Huffington Post revealed how dozens of current and former Black employees at the BBC believe the corporation is institutionally racist.

Almost 40 years on from the establishment of the Voice, Britain continues to have a vibrant Black independent media – spanning online, print and radio – though it is not without challenges.

The Voice has dropped circulation of its newspaper from weekly to monthly, with an aim of boosting its online presence in what it calls a “changing media landscape”.

Newer players have emerged and are hugely popular and influential – such as gal-dem, an independent online and print magazine committed to sharing the perspectives of women and non-binary people of colour.

Others, such as Media Diversified, have come and gone while leaving a lasting impact on many readers.

Meanwhile, mainstream broadcasters have also set up channels and introduced programmes aimed at Black and minority ethnicity communities.

In 2017, Edward Enninful became the first Black editor-in-chief of historic fashion magazine Vogue. On its latest cover it featured footballer Marcus Rashford and mental health campaigner Adwoa Aboah among other activists, largely from minority ethnicity backgrounds.

Bit of a surreal moment 🤯

Thank you @BritishVogue @Edward_Enninful ♥️ pic.twitter.com/vjOYiEF93I— Marcus Rashford (@MarcusRashford) August 3, 2020

EachOther has spoken to four people in the industry about the enduring importance of independent Black media.

You often find yourself pulling your punches [in the mainstream media] and not really saying the truth, because you know how it’ll be presented.

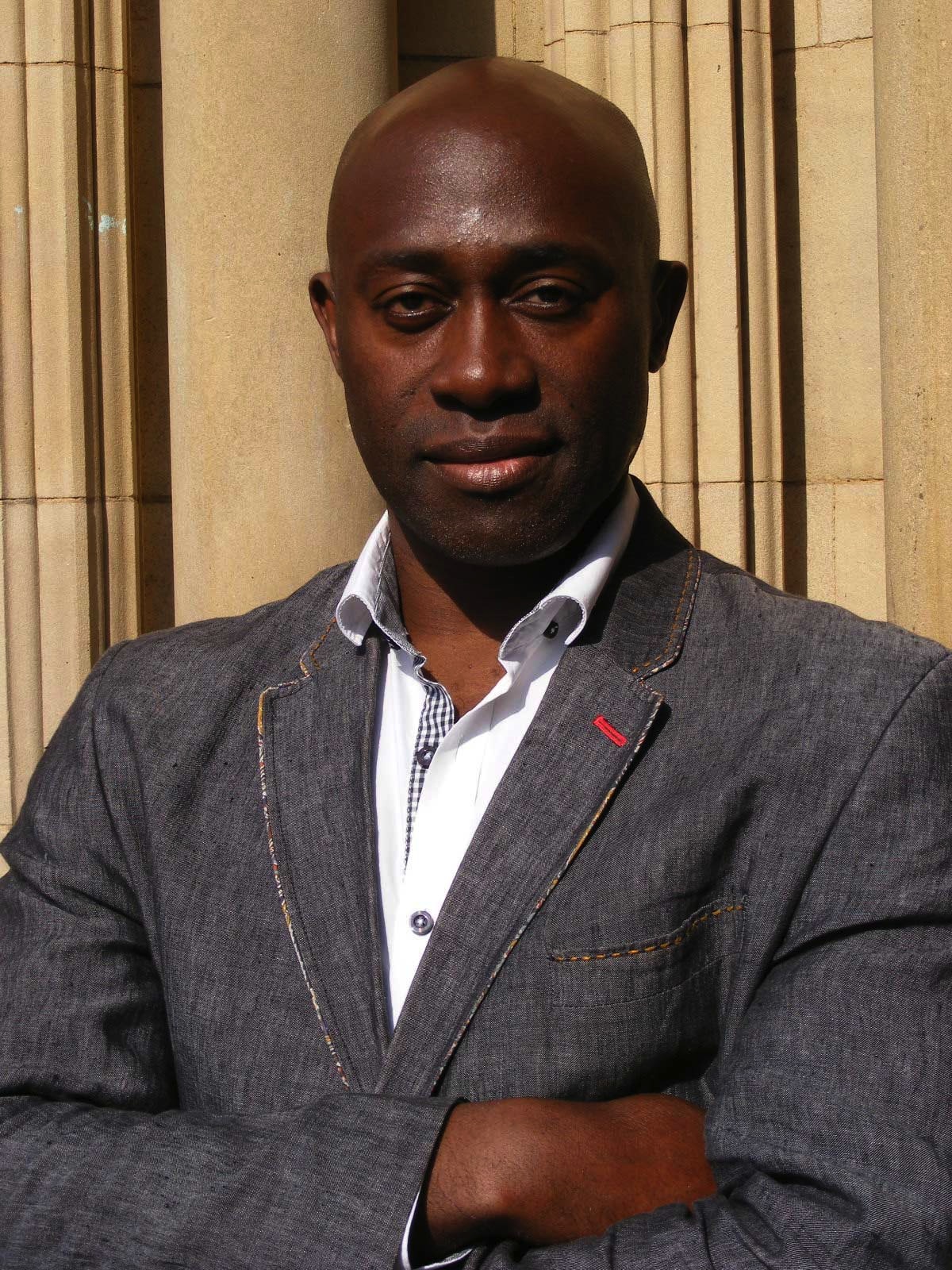

Henry Bonsu

Henry Bonsu. Credit: Supplied

Journalist and broadcaster Henry Bonsu, who was reportedly (£) axed from BBC London in 2004 for being “too intellectual”, told EachOther that Black media still has an important role to play in contemporary society.

“I think there is still a place for what we might loosely call the Black media,” said Bonsu, “especially now that we’re in the midst of a culture war on both sides of the Atlantic”.

“You often find yourself pulling your punches [in the mainstream media] and not really saying the truth, because you know how it’ll be presented,” he said.

He added that Black journalists are often positioned in the mainstream press as a subject of tabloid debate rather than a participant in serious news reporting.

“Say we find ourselves talking about slavery or British Empire – unfortunately, the way the discussions are set up means there is very little room for intelligent discussion. It’s a bunfight, where the Black commentator is on trial,” he said.

“And this is one of the reasons we need spaces – where we can be more nuanced, get those shades of opinion, and actually discuss real history.”

Bonsu also spoke of his experiences working in the British Black media, and how that gave him more room to discuss topical issues on a more complex level.

“I worked on Colourful Radio. I supported the station with time and money for several years,” he said.

“Even though there were serious problems at Colourful, I was able to speak more freely on that station than anywhere else.

“But often when it comes to more mainstream media outlets, they’re not thinking necessarily ‘our audience wants to really be enlightened here’. They’re thinking: “Our audience wants to be riled up, as we saw in the recent Rule Britannia fiasco“.

“And that’s one of the reasons I think there is still a role for Black, independent media platforms, that can influence these debates.”

However, he did point out that it’s important that Black journalism doesn’t become too insular, and that Black journalists should be free to apply their trade anywhere.

“We shouldn’t just be talking to ourselves,” he said.

Mainstream media outlets are often not thinking necessarily ‘our audience wants to really be enlightened here’, says Henry Bonsu

Black stories in [the] mainstream always seemed to be filtered through the lens of race, or trauma, they’re rarely celebratory.

Eva Simpson

Eva Simpson, founder of public relations firm ES-PR and columnist for the Daily Mirror, said there have been many historic and successful Black UK-owned media brands – The Voice, New Nation, The Weekly Journal, Pride and Choice FM.

But, as more Black stories started to be covered in “mainstream media,” Black media outlets were impacted economically because fewer people bought them, hurting their sales and advertising revenue.

“The 90s were the heyday for Black media in the UK. I worked on the New Nation and we filled a gap when it came to the underreporting of Black stories. The Voice had a Political Editor in the Lobby.

“But what you found is when mainstream newspapers started covering Black issues, sales in the Black-owned media went down and many sadly closed.

“It is important to have Black owned media – it is economically empowering, generates opportunities for Black journalists, photographers, producers and its stories speak to Black audiences.

“Black stories in [the] mainstream always seemed to be filtered through the lens of race, or trauma, they’re rarely celebratory.

“What’s great about the era we’re in now is there are so many opportunities for black creatives to tell stories, that is where the growth is – the idea that you need to be in the mainstream to have ‘arrived’ is nonsense.

“To paraphrase Jay Z: own your masters.”

The need is for better representation and educating non-Black people about how to better approach Black stories.

Hannah Ajala

Hannah Ajala. Credit: supplied

Hannah Ajala is a journalist and works with We Are Black Journos, an event platform celebrating and connecting Black journalists and those aspiring to work in broadcasting.

She said that Black communities are well-served by a number of “brilliantly Black-run platforms,” which play an important role and tend to be “unbiased, relatable, and representative.”

“The need is for better representation and educating non-Black people about how to better approach Black stories,” she said.

She said the lack of diversity in the mainstream media results in the stories being covered being done in a narrow, one dimensional way.

“This is why diversity is nowhere near a box ticking exercise,” she said.

“If there was more of a presence of Black journalists, for example, working within different teams, there would be a better approach and understanding when discussing particular issues affecting the Black community.”

As long as there is such an imbalance in terms of systemic racism societally, media misrepresentation and woeful diversity in the newsroom there will always be a dire need for Black outlets to cover our stories accurately.

Kemi Alemou

Kemi Alemou. Credit: supplied

Kemi Alemou is features editor at gal-dem, and said Black media is essential to address an uneven media landscape stemming from institutional racism.

“As long as there is such an imbalance in terms of systemic racism societally, media misrepresentation and woeful diversity in the newsroom there will always be a dire need for black outlets to cover our stories accurately,” she said.

“However even in lieu of that there are just a multitude of stories to be told about our communities that lend themselves to different mediums, TV, film, podcasts etc bond our community together through our shared experiences.”

When it comes to writing for the mainstream media, Alemou said there is a place for Black people there but it sometimes feels quite emotionally fraught.

“Are they only going to reach out when they feel they want a Black voice on a certain Black topic?” she said.

“Are places willing to commission Black writers for features, not reactive op-eds, that mine them for trauma?

“Will the editor do the piece justice and handle it sensitively if need be?”

And this feeds into why Alemou believes there’s an important place for the Black media.

“With Black-owned media, you don’t have to question whether you have to perform your blackness for them, whether you have to squish your ideas through a mould to make it more palatable for an audience that doesn’t get you, or even see or respect you as a real journalist,” she said.

I was so overwhelmed that someone saw what I was doing and thought it was good enough to write about it.

Ife Thompson, founder of Black Learning Achievement and Mental Health (BLAM UK)

On Tuesday, guest-editors from our month-long takeover spoke of the importance of an independent Black British media from their perspective as readers, contributors and sources during an online panel discussion.

Ife Thompson, a barrister and founder of Black mental health charity BLAM, said: “A lot of time I will reject somebody asking me to speak at a right-wing leaning talk-show because I feel like they’re going to gaslight me, and they make me feel uncomfortable and like I have to defend my blackness.

“I don’t have the strength, I don’t have the capacity to be doing that, I’m sorry; I need places where I’m understood,” she said.

“The first news article that ever covered what BLAM [Black Learning Achievement and Mental Health] was doing was the Voice; we didn’t get any time from anyone else.

“And for me it was really important. I was so overwhelmed that someone saw what I was doing and thought it was good enough to write about it. It was a Black journalist and it was really nice.”

Kehinde Andrews, professor of Black Studies at Birmingham City University, spoke of the barriers he continues to face in getting commissioned to write pieces for newspapers such as The Guardian.

“If you look at the people who decide what’s getting published, what’s going on TV, it’s incredibly white, incredibly elite, incredibly privileged,” he said of the mainstream media in general.

CharitySoWhite’s Martha Awojobi spoke of the importance of reading Black media outlets for her mental health.

“Going on gal-dem, I think: ‘oh gosh, people actually care about me, they’re interested in the barriers I face as a person. They’re not belittling me or gaslighting me.’”