Over the past twenty years, the proportion of prisoners from religious minorities has steadily increased. EachOther asks how can listening to minority voices improve the right to religion in prisons?

Since 2002, the number of Muslim prisoners in English and Welsh prisons has risen by 8%, the highest increase of any religious group. In London, in particular, 27% of the incarcerated population is Muslim, compared with 16% nationally. Despite these large and growing numbers, prison authorities continue to impinge on the rights of religious prisoners in general, and Muslim inmates in particular.

A former prison officer once described how the officers she worked with wouldn’t wake up Muslim prisoners for pre-fast meals because they’d decided the men were unlikely anyway to commit seriously to fasting. As a result of that decision and the absence of alarm clocks in prisoners’ cells, the former officer herself took responsibility for waking the Muslim prisoners to eat before fasting during Ramadan, despite having received no training on religious needs. “I’m looking after 80 men,” she told Maslaha, a charity which tackles inequalities affecting the British Muslim community. “I shouldn’t be learning on the job.”

Illustration from Maslaha’s ‘Time to end the silence’ criminal justice project. (Credit: Maslaha via Nur Hannah Wan and Jess Nash)

In 2017, a report called Tackling Discrimination in Prison, published by charities the Zahid Mubarek Trust and the Prison Reform Trust, found that 15% of complaints about discrimination in prisons were based on religion. The majority of these complaints focused on issues regarding dietary requirements, facilitating religious worship and access to a chaplain of one’s own faith.

“We found [in our own research] that prayer mats get mistreated,” Lauren Nickolls, Senior Project Manager at Maslaha, says. “Whether that’s intentional or a complete lack of understanding, it can be massively disrespectful.”

Religious observance can serve as an important part of a prisoner’s rehabilitative experience, including through access to religious chaplains and reflection during prolonged hours of seclusion. But, “there’s a tendency to view religion in strictly instrumental terms,” says Kimmett Edgar, Head of Research at the Prison Reform Trust, an independent UK charity working to create a humane and effective penal system. “This means not accepting religion as a fully genuine, personal commitment. Often, a conversion is viewed as the prisoner wanting a better diet or to make it look good on their probation application.”

Viewing religion as purely instrumental can lead to the restriction of religious freedom by prison authorities. In one of the “starkest examples of [religious] discrimination…authorities were aware that Friday prayers were an important day for Muslim prisoners and were using it as a mechanism for control and punishment,” says Nickolls. “Nearly everyone we spoke to had been threatened with not being allowed to go to Friday prayers, sometimes on a long-term basis, and there was no scrutiny of that decision.”

Religious prisoners are sometimes also racialised by prison officers, who band diverse members of a racial group together under reductive stereotypes. This occurred, for example, when a Black Jewish prisoner was taken off the list for kosher meals and had to ask to get reinstated by affirming his religion as well as his race.

Of the 101 complaints made by prisoners studied in the 2017 Tackling Discrimination report, only 11% were fully upheld.

For Muslim prisoners, 40% of whom say that they have received verbal abuse from prison officers, discrimination reflects a wider misrepresentation of Islam and within society. One of the main grievances reflected in findings from a thematic review of Muslim prisoners’ experiences by the HM Chief Inspector of Prisons showed that, despite only 1% of Muslim prisoners being convicted with terrorism charges, and despite the diverse ethnicities of the Muslim prisoner population, they were often viewed by staff as a homogenous group, rather than individuals, and “too often through the lens of extremism.”

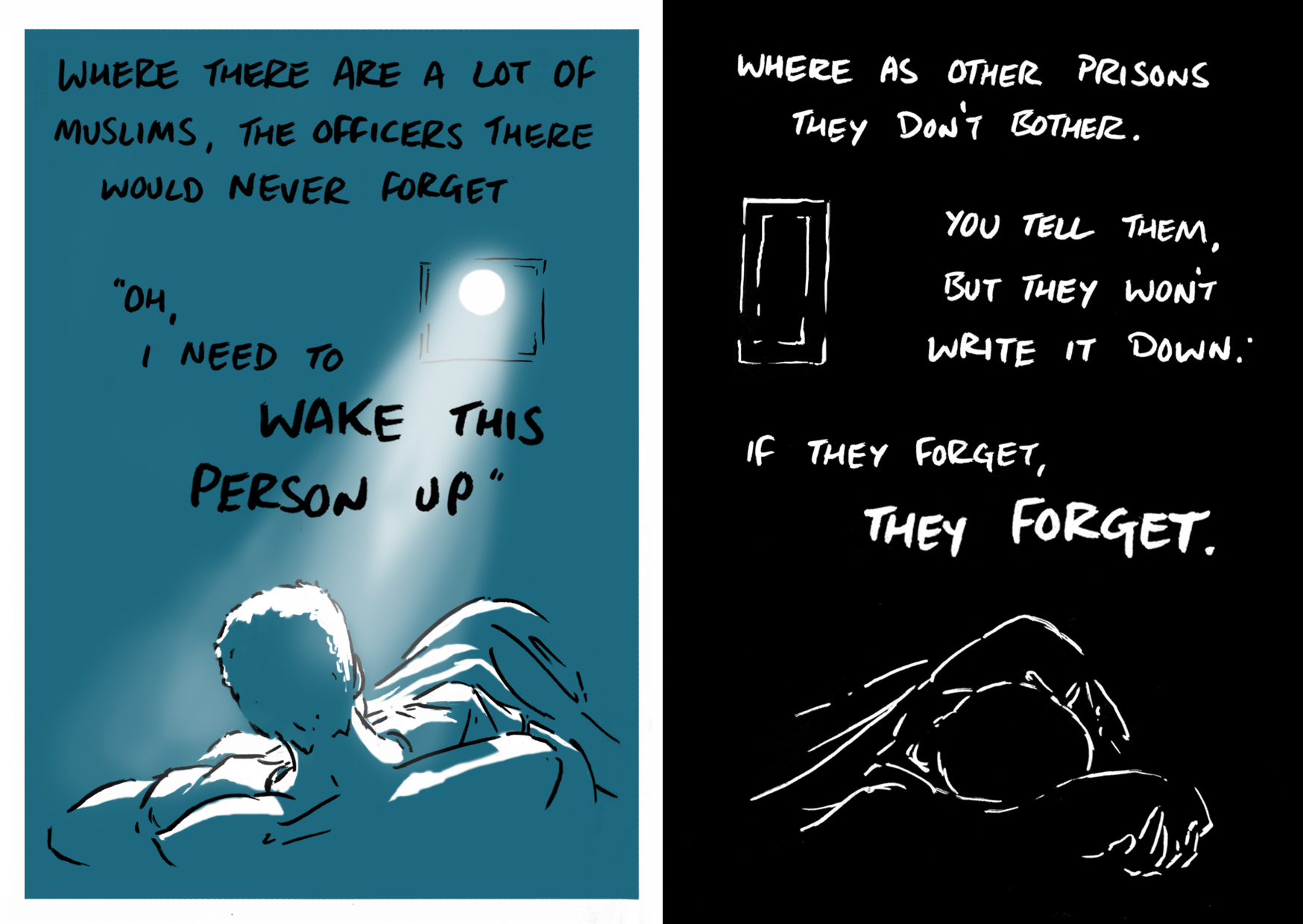

Comic style cartoon from Maslaha’s recent ‘Realities of Ramadan in prison’ project. (Credit: Maslaha/Hannah Berry. Instagram: @streakofpith)

Profiling Muslim prisoners through a lens of suspicion directly impacts prisoners’ religious freedoms. “Through praying more, or praying out loud…they would experience a shift in attitude from the prison authorities who saw this as something to be wary of,” says Nickolls.

Of the 101 complaints made by prisoners studied in the 2017 Tackling Discrimination report, only 11% of these were fully upheld, despite the Prison Service Instruction on policy for prison and probation professionals in England and Wales explicitly stating that complaints must be recognised and investigated.

This lack of accountability in UK prisons is rooted in a systemic neglect of the right to freedom of religion in the penal system. “On a basic level, a lot of these issues are about [the lack of] education of staff, as a lot of officers, like people in wider society, don’t have religious literacy,” says Sara Hyde, who previously worked in prisons and whose current PhD research at the University of Nottingham looks at social justice in the criminal justice system

White prison officers, who make up 92% of the prison officer population, dominate the staff with whom prisoners from minority groups must interact .

As a result, when complaints about religion are made, they are sometimes investigated without reference to equality. According to a prison reform report by Zahid Mubarek Trust, “a prisoner complained that officers refused to escort him to prayers. The equality officer apologised to the prisoner that he had missed prayers, but concluded that there had been no discrimination.”

“Training is often done online, so it can be very tick-box rather than understanding the issues taught by people from that religion,” adds Nina Champion, Director of the Criminal Justice Alliance, a network of 160 organisations working towards a fair and effective criminal justice system. “ The equalities lead in prisons also had other roles, with equalities just bolted on the side, so you often won’t have someone fully-focused on equality issues.”

Comic style cartoon from Maslaha’s recent ‘Realities of Ramadan in prison’ project. (Credit: Maslaha/Hannah Berry Instagram: @streakofpith)

Broader structural issues with policy processes can also impact the quality of service for religious inmates in prisons. Equality Impact Assessments, which are evidence-based processes intended to ensure that policies do not discriminate, “are often done once the policies have already been formulated, retrospectively,” says Champion. “These assessments should be done at the start and should inform the policies that go along. They should also be co-produced with organisations that work with minority communities.”

But, while smaller organisations such as Maslaha, or the Muslim Women in Prisons Project, specialise in providing research on the treatment of minority religious groups, “they don’t necessarily get funding through the commissioning model,” says Champion. “They’ll be rejected rather than being told, ‘We know you can reach this group, so how can we work better with you through grant funding rather than contracts, or get rid of the red-tape to make sure that funding is reaching the organisations on the ground?’”

The erasure of minority experiences within equality impact assessments perhaps reflects the under-representation of officers from minority communities. White prison officers, who make up 92% of the prison officer population, dominate the staff with whom prisoners from minority groups must interact. “If we, the staff, look like or come from a similar background to our prisoners, then they might feel a bit more comfortable coming to us with a problem,” says Fiona Merrifield, a senior leader in the prison service.

“Prisons are based on everyone waking up at the same time, everyone has their lunch, everyone goes to work, everyone is locked back up in their cells,” Hyde says. “It’s a rigorous regime with little room for flexibility for aspects of faith that we take for granted.”

Failure to engage with religious minorities and diversify the prison staff population means prison authorities continue not to understand the importance of religion for many prisoners and so infringe their right to religious expression. The growing body of research about religious minorities’ experience in prisons by specialist organisations such as Maslaha and the Prison Reform Trust, however, means the pressure is mounting on policymakers in the penal system to respect the right to religion.