“I truly believe that without that class, I wouldn’t be who I am today,” said André Skepple, 33, of the pan-African Saturday school he attended in his youth.

It was not until he was 21 and at university that he was diagnosed with dyslexia and dyspraxia.

He felt these learning difficulties contributed to him underperforming in his A-levels, but were “dismissed out of hand” by his mainstream secondary school due to him being black and his teachers’ ignorance of neurodiversity.

However from the age of five to 16, the father of one attended additional classes on Saturdays at the Nubia African Community Foundation School in Clapham, south London.

It is to these classes that Skepple, who now has a Master’s degree and runs his own online education technology business, credits his success.

“To be very, very direct, that class was the making of me,” he told EachOther.

“It provided a knowledge of self, a knowledge of history that is seldom covered … the Sudanese and ancient Egyptians and the west African empires.”

It also equipped him with the knowledge he needed to resist institutional racism within his mainstream schooling, he added.

“I understood how the game is played. I am expected to be disruptive. I am expected to work four-to-eight times harder in order to get the grades to achieve,” he said.

“There was no room for error in that [mainstream] school or environment.”

Andre Skepple said Saturday school gave him life-changing career opportunities. Credit: Supplied

It is a lesson echoed by British rapper and writer Akala, who has spoken on numerous occasions about attending the Winnie Mandela Saturday school in London.

“I learned, as my friend the scholar MK Asante says: ‘take two sets of notes,’” he says in a video on his YouTube channel. “Take the sets of notes you need to pass the test at regular school and you take the notes you need for yourself to navigate life.”

“They would ask the children questions like: ‘does the dirt just come back on when you wash?

Bini Brown, founder of Sankofa Sesh Saturday school in Birmingham

The supplementary school movement traces its origins back to the 1960s, instigated by black parents who saw their children experience racism in class.

It saw parents, teachers, community activists and church leaders form grassroots volunteer-led schools, with most taking place on Saturdays.

Core subjects such as Maths and English were taught alongside pan-Africanism and black history to counteract the skewed perceptions black children were being given about their culture.

Bini Brown, who helped to establish Birmingham’s Sankofa Sesh, one the oldest supplementary schools in the country, told the Voice in 2013: “Teachers were racist.

“They would ask the children questions like: ‘does the dirt just come back on when you wash?”

“Children were going to school and weren’t learning, but they would come to our school and in weeks we got them reading, writing and doing their mathematics.”

Sankofa Sesh, founded in 1967, faced battles with the police and local education authorities during its establishment.

Alongside the schools came the wider Black Education Movement, the Black Parents Movement, the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association and the Anti-Banding Campaign, who opposed the introduction of IQ testing in primary schools.

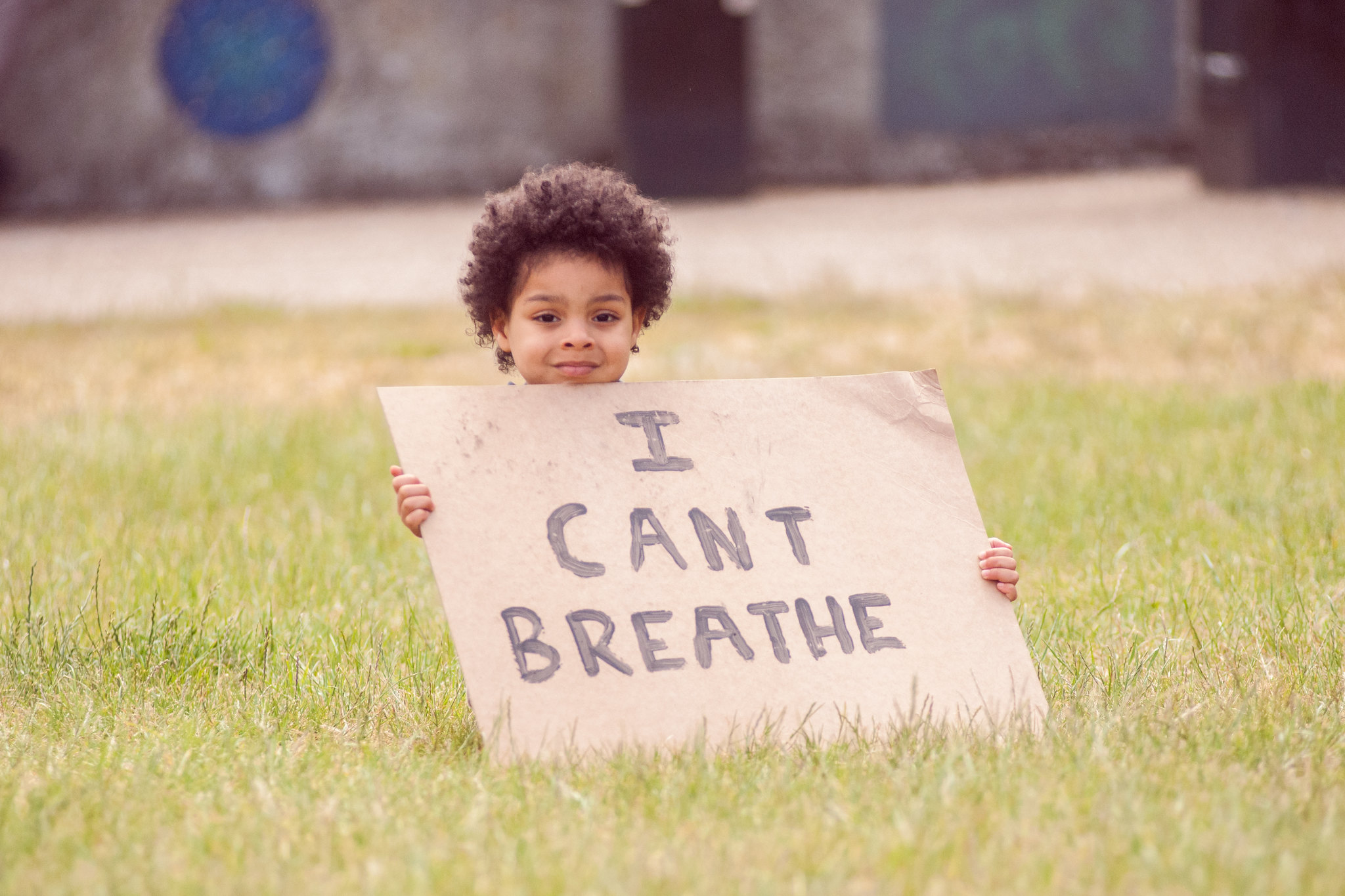

Young protesters at a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Sheffield. Credit: Flickr / Tim Dennell

Six decades on, the supplementary school movement continues in Britain – although numbers have declined.

Nia Imara, founder of the National Association of Black Supplementary Schools, estimates that there are currently as many as 25 schools in Britain in 2020 – down from about 50 seven years ago.

However, the grassroots nature of the movement makes it difficult to keep precise records as more spring up.

In light of the pandemic and recent Black Lives Matter protests, what does the future of the movement look like?

“It’s looking positive actually,” Imara said.

The resurgent BLM protests have seen him inundated with calls from parents interested in enrolling their children in classes or setting up their own schools.

Meanwhile, Covid-19 has accelerated a trend towards sessions moving online – while some schools are set to try a combination of face-to-face and online classes. However, some classes are not going to open again, he acknowledged.

For Imara, the continued need for supplementary schools is evident.

“The curriculum is down to the schools’ choices and individual teachers’ choices,” he said.

GCSE exam data analysed by the Guardian shows that, while schools are permitted to teach black history, few of them do.

It found that up to 11% (approx 28,412) of GCSE students in 2019 were studying modules that made any reference to black people in British history.

The history modules of England’s three biggest GCSE exam boards make more references to black people in the US, other countries, or the transatlantic slave trade, than to black Britons.

This is despite there being black people in Britain since as early as the arrival of the Romans.

Nia Imara, founder of the National Association of Black Supplementary Schools. Credit: Supplied

Imara saw this starkly as he visited his daughters’ school in Camden recently, and noticed all the pictures being displayed on the walls were of white people. Their teacher explained to him that they were studying the Second World War.

“Ok so, where are the black people?” Imara asked the teacher. “How can you be doing something around the Second World War when they played a significant role in us not speaking German right now?”

Some 10,000 men and women from Britain’s former colonies left their homes to join the British armed forces, working behind the scenes and on frontlines to defeat the Nazis.

“The teacher explained: ‘I haven’t got that information’,” Imara said.

What is the consequence of this distorted picture of history in schools?

“You feel like we have not achieved anything,” he said. “You want to disown your history.”

Looking beyond the curriculum, there are continued reports of black children being unfairly punished for hairstyles, kissing teeth and wearing bandanas.

Meanwhile, black pupils face an exclusion rate three times higher than their white peers in some parts of England.

Professor Kehinde Andrews chronicled the history of Britain’s black supplementary school movement. Credit: Supplied

Kehinde Andrews, a professor of Black Studies who is guest-editing EachOther this week, is believed to be the first academic to chronicle the radical history of Britain’s black supplementary school movement.

In his 2018 book Back to Black: Black Radicalism for the 21st Century, he writes that a split has now emerged between schools he describes as ‘official’ versus those offering ‘self-help’.

The main purpose of the former schools, which take state funding and have now come to dominate the movement, “is to boost the grades and performance in mainstream schools, not to provide Black education”.

While the latter “remain independent from the state and its politics” and committed to the movement’s roots in indicting the mainstream school system.

He writes: “Black supplementary schooling is the perfect example of the state funds and accommodates a grassroots movement into the system.”

Asked about the future of supplementary schools, Skepple is supportive but said he is also skeptical.

“It has always been a battle for their existence,” he said, referring to how projects would spring up in people’s houses, community centres and churches amid battles with local authorities.

He warns that supplementary schools will need to be careful in their transition towards online learning methods, to ensure they are responding to children’s learning needs as effectively as they are more easily able to do face-to-face.

He is also wary about the emerging trend of businesses announcing their allegiance with Black Lives Matter and rolling out corporate social responsibility programmes in a bid to support, or be seen as supporting, anti-racism.

Such funding could bring with it the risk of supplementary schools losing their “core essence” and being used to serve “alternative agendas”, he warned.

Nevertheless, Skepple is certain that he will send his three-year-old son to a Saturday school. And, since graduating from the Nubia school, he has returned to teach on multiple occasions.

To that end, amid these challenges, the fight for black pupils’ right to a more complete education continues.