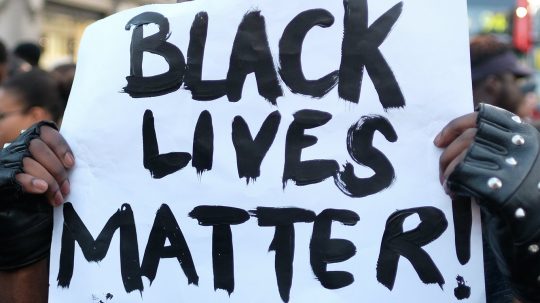

As the Black Lives Matter protests spread from the US across the globe, there was an outpouring of support from UK lawyers. More than 250 barristers and solicitors signed up to Black Protest Legal Support UK to act as independent legal observers – monitoring police conduct at the BLM marches and informing the thousands of people taking part about their rights. It gives me hope that a new approach to being a lawyer could become the norm in the UK, an approach which sees us work together to support communities from the ground up.

In the US, this is already a well-known and championed concept called “movement lawyering”. It is defined by University of California legal expert Betty Hung as a practice which “supports and advances social movements […] led by the most directly impacted, to achieve systemic institutional and cultural change”. Law 4 Black Lives, a 4,000-strong network of radical lawyers across the US, also describes the concept as “taking direction from directly-impacted communities and their organisers, as opposed to imposing our leadership or expertise as legal advocates. It means building the power of the people, not the power of the law.”

“Movement lawyering”, which aims to transform society with direct support from affected communities, appears to be a less well-known concept in the UK. Perhaps the closest thing we have to it is the idea of “radical lawyering” – but this concept seems to focus more on individual lawyers who rally against injustice.

I would advocate that now is the time to outright create a movement in the UK that is centered on social and racial justice within the explicit idea of movement lawyering. More lawyers need to be working directly with communities on social movements, giving them the chance to create grassroots change within a legalised framework.

Evelyn A. Williams: a blueprint for movement lawyers

A mural of Assata Shakur. Credit: Gary Stevens / Flickr

An important case study in movement lawyering can be found in the work of Black defence attorney Evelyn A. Williams, who represented many members of the Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army (BLA) including her niece Assata Shakur.

Shakur had been targeted by Cointelpro, the US’ secret counterintelligence agency, which law firms such as the People’s Law Office revealed sought to “neutralize” the Panther movement. Between 1971 and 1973, Shakur was falsely accused of committing a series of serious crimes, sometimes alongside other members of the BLA. This included two bank robberies in New York, the kidnap and murder of a drug dealer, armed robbery, and the attempted murder of policemen in ambush. Represented by her aunt Williams, in all of these trials she was either acquitted or the case dismissed.

In her 2000 autobiography titled “Inadmissible Evidence”, Williams speaks of how she adopted a specific understanding of the Black liberation struggle in preparing for and conducting her clients’ cases. Williams says: “representing cases that advanced social movements required constant change and adjustment from my long practiced academic and technical approach […] I was legally knowledgeable, but I did not have a political strategy, so I made a pact with Assata that she could do her thing.”

When Williams talks of Shakur’s “thing,” she is referring to tactics such as allowing the activist to act as co-counsel in cases so that she could directly speak to the jury. In one instance Shakur held a protest outside the court and in another her legal team were held in contempt of court after staging a walkout.

However in 1977, Shakur was convicted of the 1973 murder of a state trooper after police pulled over a car filled with BLA members which led to a shootout. Shakur maintains her innocence, highlighting how the FBI’s own forensics show that she didn’t handle any weapon found at the scene. The jury is reported to have been filled with relatives, friends and partners of state troopers. Meanwhile, there was also evidence that Shakur’s defence team were being bugged, and materials relating to her case which went missing from the home of her late attorney were later found with the New York City police.

And I have come to the [conclusion] that Assata reached a long time ago: direct action by the people is the only hope for change.

Evelyn A Williams

In spite of this, Williams’ approach aided in securing three jury acquittals for Shakur. Williams later opened her own office to further serve and be among the community. Her commitment to community lawyering is seen in the afterword of her book, when she writes:

“While the daily practice of law is no longer a part of my life, I still accept challenging cases, but I spend equal time reading African history, relearning African art, painting shells with Black liberation colors (black, red and green). And I have come to the [conclusion] that Assata reached a long time ago: direct action by the people is the only hope for change”.

This shows us that movement lawyering involves lawyers being part and parcel of the community and most importantly listening to their needs.

Michael Mansfield QC. Credit: Flickr / GUE/NGL

Even when we even look at the history of law centres in the UK, the idea was inspired by what was happening in the US. Peter Kandler, who co-founded North Kensington Law Centre 50 years ago, said the organisation was “bringing the law to the people”. Since its inception they have been able to support countless members of the community in their local area. There are now 40 law centres across the UK. Law centres enable us to visualise what the future of movement lawyering in the UK could look like. It actively shows how easily concepts that seem new, can become the norm.

The importance of community-based law offices has also been promoted in the UK by Michael Mansfield QC, who has been involved in countless high-profile human rights cases.

In his 2010 book, Memoirs of A Radical Lawyer, he writes about the Acre Lane Neighbourhood law firm established in Brixton during the 90s – “an idea ahead of its time by trying to directly serve the community” rather than being remotely situated in central London’s luxurious Inns of Court.

He writes: “The change in the economic wind (legal aid cuts) may force barristers to relinquish lavish and expensive premises in city centres in favour of much smaller, collectively resourced offices. This will permit the growth of satellite branches at a local level within the community. Back to grassroots.”

UK movement lawyering by another guise?

The life and work of the late Ian Macdonald QC can be seen as a clear example of movement lawyering in action within the UK. Macdonald was involved in supporting the Black Parents Movement and the Mangrove Nine – a group of Black activists who were tried and acquitted after being subject to police violence during a protest against the racist targeting of a restaurant in west London’s Notting Hill.

The Mangrove Nine trial was a watershed because we learnt through experience how to confront the power of the court, because the defendants refused to play the role of ‘victim’ and rely on the so called ‘expertise’ of the lawyer.

Ian Macdonald QC

In an article for Race Today, Macdonald beautifully typified and conceptualised what movement lawyering is, and why even some radical lawyers may not even fall firmly within it.

He writes: “The self-activity of the defendant in the court proceedings is denied. However great the defendant’s rebellion up to the time of arrest, it must stop at the door of the court.

“Courtrooms are places for professionals, and defendants must follow a certain code of behaviour and sit docile and passive in the dock. The ‘good’ lawyer then bargains with the court about their fate.

“Unfortunately, this is probably a correct description of the normal lawyer-client relationship in criminal cases … This type of advocacy never challenges the power in the courtroom … What some radical lawyers ignore is that people like the Black Parents Movement come into that organisation with a very particular experience of dealing with courts and the police.”

Barbara Beese was a member of the Black Panthers and one of the original Mangrove Nine. After the march Beese was arrested and charged on a number of accounts. She was found not guilty on all. Credit: National Archives

He continues: “The Mangrove Nine trial was a watershed because we learnt through experience how to confront the power of the court, because the defendants refused to play the role of ‘victim’ and rely on the so called ‘ expertise’ of the lawyer.

“Once you recognise the defendant as a self-assertive human being, everything in the court has to change. The power and role of lawyers – the advocacy and the case preparation … What all radical lawyers have to decide is whether they want to retain their slice of the traditional lawyers cake or to participate in a bold new experience.”

Community activist Gus John notes the importance of Macdonald’s movement lawyering style in his recent obituary:

“Ian became a champion of a method we in ‘The Alliance’ of the Black Parents Movement, the Black Youth Movement, Race Today Collective and Bradford Black Collective adopted of placing defendants at the centre of their defence against police/CPS prosecution and having solicitors and barristers work with their testimonies and not be led by their instinctive reactions to the police/prosecution’s account of events and the circumstances surrounding them.”

“This approach was crucial not just in cases involving individual young people or adults, but in prosecutions arising out of civil unrest (rebellions, demonstrations, sit ins) and police surveillance.”

We can appreciate that, even if we in the UK are not familiar with the framework of movement lawyering, the work of many radical lawyers shows us how movement lawyering under another name has had a profound legacy, particularly within Black community activism. I have read three different UK books about Black-British activism during the 1970s and 80s and Ian Macdonald features within each of them. This speaks to his dedication to knowing the community he worked with and centring their voices. Something more of us must strive to do.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.