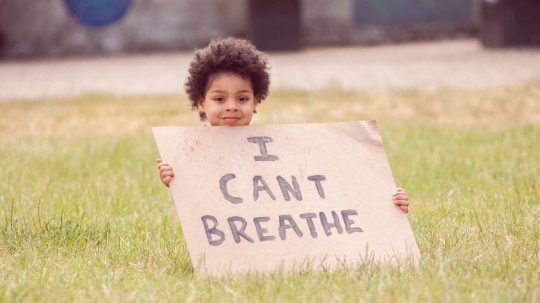

Schooling in the UK was thrown into disarray as Covid-19 took hold this spring, with final year A-level students from working class and/or Black, Asian and minority ethnicity (BAME) backgrounds among the hardest hit. EachOther speaks to three working-class Black A-Level students from London ahead of results day to understand their concerns.

At the beginning of the pandemic, prime minister Boris Johnson ordered all schools to close from 20 March, with exams across the country cancelled.

The government has said students who were due to sit A-level exams will instead receive a “calculated grade”, with schools and colleges providing a “centre assessment grade” for each subject.

This grade will be based on what the student would have been “most likely” to achieve, taking into account non-exam assessment and mock results.

The government is putting centre assessment grades through a process of standardisation developed with Ofqual, the independent qualifications regulator.

However, concerns have been raised over the fact that nearly 40% of A-level grades submitted by teachers are set to be downgraded by Ofqual’s algorithm, affecting around 300,000 A-levels.

This follows a similar trend seen in Scotland, which released its A-level results last week, where students in the poorest areas were worst affected by downgrading. The Scottish government has since apologised and upgraded the results of tens of thousands of pupils.

Yesterday night, in an “eleventh-hour” move, Education Secretary Gavin Williamson announced that schools in England will be able to keep mock A-level results if they are higher than moderated grades. The government is referring to it as a “triple-lock”.

Today, he told the BBC: “I apologise to every single child right across the country for the disruption they have had to suffer.”

However, this does not fully address the concerns of Black students from working class backgrounds, who face an even more anxious wait due to inequalities in Britain’s education system.

Research by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills in 2011 found Black applicants had the lowest predicted grade accuracy, with only 39.1% of grades accurate, and are most likely to have their grades under-predicted.

Research by the University of Birmingham has found that 82% of white pupils are satisfied with how their school has managed the pandemic, but it drops to 72% for Black students and 42% for Asian students.

Kam Nasser

Nasser, 18, studied maths, physics, and French, and hopes to go on to do engineering at university.

I have really no idea what to expect.

Kam Nasser

State-educated, like many within his cohort, he has expressed concern about the incoming examination results.

“I’m feeling apprehensive about A-Level results day – both for myself, and for many of my friends,” he said.

“I have really no idea what to expect.”

He added: “I feel as though students from disadvantaged backgrounds will have their results downgraded the most.

“I also worry that Black students, like myself, who are underestimated by their teachers more often than their white counterparts will end up with worse grades.”

These fears are not unfounded. Ofqual’s deputy chief regulator, Michelle Meadows, told the Commons Education Committee in July: “There is some evidence of bias.

“For the most able students [with an ethnic minority background], there tends to be under-prediction of grades that student go on to get.”

When it comes to the future, Nasser hopes the Department for Education (DfE) ensures every student who was on track to enter higher education can do so. He also hopes the qualifications gained by this year’s cohort aren’t considered to “be of less worth” and is concerned about this perception affecting his job prospects amid the UK’s largest recession on record.

Yaw Junior Abrampah Danquah

Abrampah Danquah. Credit: Supplied

Abrampah Danquah studied physics, chemistry, and maths and hopes to go on to do chemistry with medicinal chemistry at the University of Warwick.

He attended a state school, and says he is avoiding focusing on his feelings about the examination results.

“It’s completely out of my control,” he said.

“Worrying increases stress by tenfold, for the protection of my own sanity: what else can I do?”

Like other Black students, Abrampah Danquah said that he did not believe the results would reflect the abilities of students – and spoke of the importance of having a second opportunity to resit exams.

“Everyone deserves that final chance to redeem themselves.”

And while he expressed that he takes accountability for his examination outcome, he also said that “racial bias will play a bigger role.”

This is echoed by Poornima Karunacadacharan, senior policy officer at equality charity Race on the Agenda (Rota).

Speaking to EachOther, she said: “The standardisation process used by Ofqual will have a disproportionately adverse impact on BAME and working class pupils.

“Ofqual have been more concerned about maintaining the status quo, which entrenches inequalities, [rather] than taking steps to address bias within the system.”

However, Ofqual has previously insisted its standardisation model is “a critical tool” to make sure standards were broadly similar to previous years.

In July, an Ofqual spokesperson told the Guardian: “We have extensively tested the model to ensure it gives students the fairest, most accurate results possible and, so far as possible, that students are not advantaged or disadvantaged on the basis of their socioeconomic background or particular protected characteristics, and we will evaluate outcomes.”

Karunacadacharan also expressed the need for a proper appeals process, “If, in England, the government does not reverse the decision to use algorithms that use previous years grades in a way that disadvantages BAME and working class pupils, there must at least be a widely accessible and fair appeals process,” she said.

Local authorities and equality charities have raised concerns that individual students have no right to appeal the grade they have been given through Ofqual’s standardisation process – but must instead do so through their schools. This could leave students who wish to appeal in an “impossible position” if the school disagrees.

Moving forward, Abrampah Danquah said he would like to see “a much more student driven approach” when it comes to deciding which universities students can attend.

Dana Anshur

Anshur attended a state school, and comes from a first generation Somali family.

She studied English literature, geography, and chemistry at A-Level, and holds an offer from the University of Cambridge to study Law.

She expressed various concerns about the imminent results.

“I was hoping to be the first person not only in my immediate family, but even my extended family, to attend university,” she said.

“I worked extremely hard so I could achieve the grades.

“In mock exams in February I achieved A*AB, so I was hoping to be on track for my real A-Levels to achieve A*AA minimum – but, obviously, Covid hindered that.”

Like Nasser, she also expressed fears not just about her own attainment, but for her peers, too.

“My school is literally predominantly working class BAME students, with a lot of students – including me – on free school meals, receiving a bursary from school to support us financially.”

She went on to say: “I wish they would’ve taken teachers predictions more seriously than school performance.

“It’s such a classist system, and basically a glorified postcode lottery.”

This is echoed in results recently released in Scotland, where research showed that predicted grades were 15% lower in poorer areas, versus 7% in wealthier areas.

The Sutton Trust, an education charity focused on class inequality, have expressed these concerns.

“Any system relying on teacher assessment risks underestimating the abilities of disadvantaged students, as teacher assessment can unconsciously disadvantage students from certain groups, such as those from lower socio-economic backgrounds,” it said in a report published earlier this year.

“For example, teachers have been found to be less likely to judge low-income students as having above average ability in reading or in maths, even when their previous test scores indicate as such.”

The DfE has been contacted for comment.