Often, when we speak about racism within the criminal justice system, we criticise policing. We lament about investigation techniques, intelligence handling, over-policing in areas home to larger black communities. When we turn to the courtroom, we criticise the disparities in sentencing; or the higher rate at which our black clients are disproportionately remanded in custody compared to their white counterparts. But rarely do we speak about how we as a profession contribute to the racism that permeates the system.

However, it is simply artificial to remove us from the realm of criticism, we are cogs in the same system as the police. The investigations they conduct and the evidence they produce provide us with the ingredients with which cases are built. Defendants rarely end up in custody without a prosecutor making an argument for their remand; and sentencing levels are guided by representations made by lawyers as to culpability and harm. So what do we actually do to fight for fair results? What do we do to be consciously anti-racist?

Many have dedicated years to our work and believe that what we do is important in securing justice, fairness and proper resolution to issues. But traditionally, our work is not about justice, it is about ensuring that due process is followed. It is not about whether the legislation and common law we apply is ‘fair’. We’re also under pressure in court. Rarely do we pause and question the systems we are working in. However, we need to make the space and time to do just that. There is a wealth of reports and data available highlighting the shortfalls in criminal law but if we as practitioners fail to engage with them, their recommendations and observations will be lost.

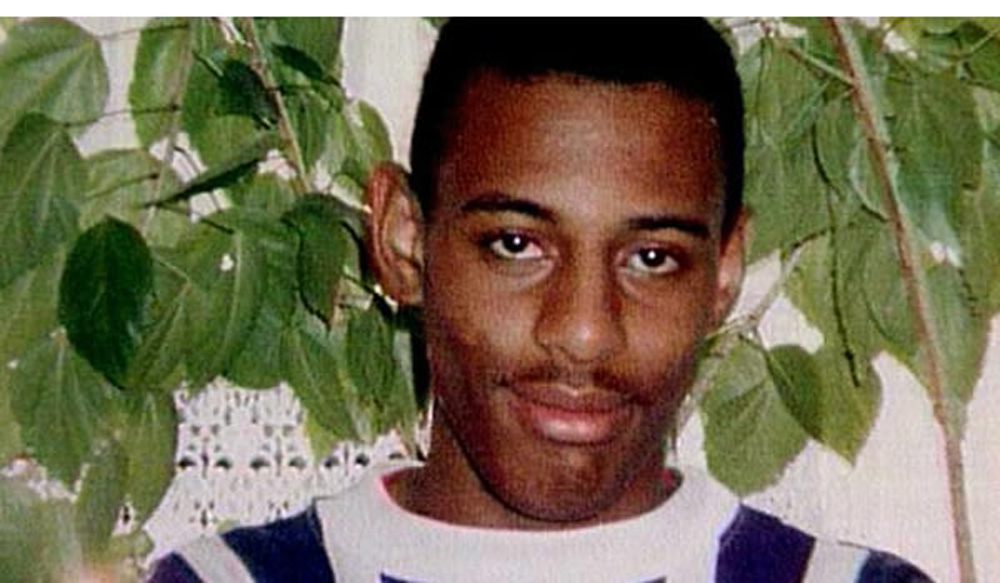

The 1999 MacPherson Report, which exposed how the investigation of the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence was marred by “institutional racism”. Credit: Flickr / Unision

Examples can be found in the 1999 MacPherson Report, which exposed how the police investigation into the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence was marred by “institutional racism”. Giving evidence to the inquiry, inspector Paul Wilson, of the Metropolitan Police’s Black Police Association, said:

“Given the fact that these predominantly white officers only meet members of the black community in confrontational situations, they tend to stereotype black people in general. This can lead to all sorts of negative views and assumptions about black people, so we should not underestimate the occupational culture within the police service as being a primary source of institutional racism in the way that we differentially treat black people.

“Interestingly I say we because there is no marked difference between black and white in the force essentially. We are all consumed by this occupational culture. Some of us may think we rise above it on some occasions, but, generally speaking, we tend to conform to the norms of this occupational culture, which we say is all powerful in shaping our views and perceptions of a particular community.”

Dr Robin Oakley then said the following:

“Police work, unlike most other professional activities, has the capacity to bring officers into contact with a skewed cross-section of society, with the well-recognised potential for producing negative stereotypes of particular groups. Such stereotypes become the common currency of the police occupational culture. If the predominantly white staff of the police organisation have their experience of visible minorities largely restricted to interactions with such groups, then negative racial stereotypes will tend to develop accordingly.”

The majority of [lawyers] are white. That whiteness informs the base culture of what we do.

Abimbola Johnson

As I read those words, I was struck by how applicable they are to our profession. The majority of us are white. That whiteness informs the base culture of what we do. Many in the profession mostly come across members of the Black community in court rooms. It is a fallacy to suppose that negative views and assumptions will not find their way into our work unless we consciously make sure they do not.

I was asked, therefore, what we should do in the court room. Well, first, we need to reach a point where we can identify the ways racism rears its head in the courts. ‘Due process’ makes it difficult to recognise implicit and unintentional racism which is just as harmful as its intentional and explicit counterparts.

Training

We should start by introducing training. When barristers study criminal procedure in Bar school, we should also be taught about institutional racism. When we learn about the ‘legality’ of a technique, such as stop and search, we should learn about whether it is actually effective, the societal impact of that technique, the data about how it is used and this should be ongoing throughout our careers.

We would make sure we are not applying only white middle class expectations of behaviour on citizens that are anything but that.

Abimbola Johnson

For those of us that are past Bar school we need to do this too.

Start therefore by reading. Reading the vast amount of information that has already been published and exposes the shortfalls of the systems we work in. The MacPherson Report is just one example. Once we do that, we’ll be able to better contextualise and analyse the evidence that makes it way to us. To contextualise and understand the reactions of people from different ethnicities and geographical areas to interactions with the police. We would make sure we are not applying only white middle class expectations of behaviour on citizens that are anything but that.

Statistics

We should be familiar with these from the outset when we consider evidence for example:

- What are the rates of stop and search by race within the local area that this particular suspect was seen in?

- How many times has this particular suspect been stopped and searched with positive and negative results?

- How many times has this officer stopped and searched black suspects compared to white ones?

- What is the level of description actually provided by witnesses that the police have relied on in this instance? Just “IC3”– which is police-speak for “Black – Sub-Saharan African or Afro-Caribbean”? Would you view that as a reasonable basis for a stop and search of a white “IC1” counterpart?

- Knowing the answers to these questions – is that evidence as compelling as it appeared on the face of it?

Education

Lets for a moment look at bad character applications – where the court can be presented with evidence of a person’s disposition towards misconduct.

In some instance school records can be introduced as evidence of ‘poor’ or ‘violent’ behaviour, implying the defendant has a propensity to commit a criminal offence. But, if we consider the prevalence of systemic racism within education, should we be so keen to rely on this?

What was the definition of this alleged poor behaviour?

Are we aware of the fact that black school children are unfairly punished for hairstyles, kissing teeth, wearing bandanas?

What about when we consider that black pupils face an exclusion rate three times higher than their white peers in some parts of England?

Pupils learning in a classroom. Credit: Unsplash

The realities of the lived experiences of others

Are we up to date with our working definitions of and abilities to spot vulnerability?

Are we engaged with the fact that children who have a history of criminality and are from certain areas that have higher proportions of gang associated individuals are more vulnerable and likely to be groomed into criminality than children from a stable upbringing?

That those children are more likely to present as hostile, savvy and uncooperative with the police? Or do we still subscribe to the idea that vulnerability is a reserve for victims and that it is demonstrated through ‘weakness’ and ‘likeability’?

If we were more clued into those factors, where would we then pitch culpability when making representations about sentence? Would we still find that there was a public interest in pursuing a prosecution in the first place? Risking further alienating them from society, marking them as criminal from such a young age, impacting future employability prospects?

The answer to the question of how we incorporate anti-racism in our work is not a simple one. It requires retraining, constant reading, and self-reflection but we should view it as essential work. How can we make informed decisions about the evidence and investigations before us if we do not also endeavour to understand the communities and people involved?

I cannot possibly cover this entire topic in one article, we need a more informed and engaged profession so that these conversations can even begin to take place in a meaningful way.

However, I hope that the above sets out reasonable starting points that we can all begin to adopt in our practices. If you would like to know more and to become more involved in developing practical steps towards change, you may be interested in following the Howard League for Penal Reform’s new project: Making sure Black lives matter in the criminal justice system.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.