Dominic Raab has announced his intention to ‘overhaul’ the UK’s Human Rights Act (HRA), despite widespread criticism.

During his first Conservative Party conference speech as Lord Chancellor, justice secretary Raab said, “There’s one other big change the public want to see. Too often they see dangerous criminals abusing human rights laws… We’ve got to bring this nonsense to an end.” Raab raised the hopes of those eager to amend or even replace the HRA when he then promised to “end this kind of abuse and restore some common sense to our justice system” before the next general election.

The government has already commissioned an independent review of the HRA, set to be completed by the end of October. It is focusing mainly on the relationship between domestic courts and the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), as well as the impact the HRA has on the relationship between the judiciary, the executive and the legislature.

In an interview with the Sunday Telegraph, Raab set out his motivations and intentions for his proposed overhaul of the HRA. The ECtHR imposed too many “obligations on the state” instead of defending individuals from “undue interference”, he asserted, before he revealed that he was working on a mechanism that would allow the government to introduce legislation to “correct” court judgements that ministers believed were “incorrect”.

“We want the Supreme court to have a last word on interpreting the laws of the land, not the Strasbourg court,” he said. “We also want to protect and preserve the prerogatives of Parliament from being whittled away by judicial legislation, abroad or indeed at home.”

In addition, Raab said it was “wrong” that Strasbourg judges ruled on matters relating to British soldiers overseas after senior representatives of the Armed Forces informed a government review that British soldiers were “in harm’s way” due to fears of legal consequences at the ECtHR.

Critics are concerned that, on this particular point, Raab has an ulterior motive.

Credit: Tingey Injury Law Firm / Unsplash

“Earlier this year ministers tried to decriminalise torture by our troops abroad, but they were defeated by a coalition of torture survivors, military top brass and principled Britons from all walks of life,” said Sonya Sceats, chief executive of Freedom From Torture. “Now they are at it again, trying to keep torture cases out of the Strasbourg court, which Britain helped to build as a safeguard against the return of authoritarianism in Europe.”

Raab is yet to release the full details of his plans for the Human Rights Act. However, he has said that “elected lawmakers” should govern public services, not “judicial legislation”. This particular grievance could refer to the ECtHR ruling that the government’s “bedroom tax” discriminated against victims of domestic violence.

Shadow justice secretary David Lammy criticised Raab’s plans. “Scrapping human rights protections because you don’t like abiding by the law, all while the justice system crumbles, the new justice secretary shows his true colours,” he said.

This latest threat to the HRA and the rights it enshrines is expected to materialise quickly, with speculation that the government will publish proposals for its ‘overhaul’ by the end of November, perhaps in the process revisiting the idea of a replacement Bill of Rights, which previous Conservative governments have mooted.

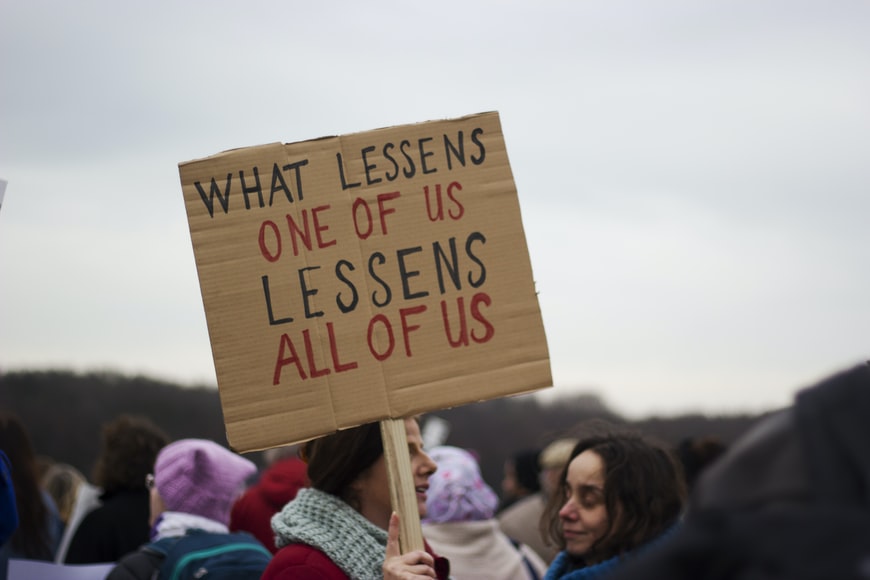

“The Human Rights Act has made many people’s lives better, allowing ordinary people to challenge governments and public authorities when they get it wrong,” said Charlie Whelton, policy and campaigns officer at Liberty. “No one should be above the law – but this statement, along with the Policing Bill, the Judicial Review Bill and the Elections Bill, shows a government that is actively planning to erode our ability to access justice and stand up to power, in the streets, in the courts, or in the polling booth.”