From landmark legal cases to a landslide general election result, and civil disobedience to constitutional upheaval – the UK had no shortage of human rights news stories in 2019.

As we step into a new year and decade, our focus turns to what 2020 will bring. Here is a list of five of issues to keep a close eye on.

We cannot offer a crystal ball so much as a foggy window into the future. These issues are not all new and are in no particular order. But it seems likely to us that they will feature at the top of the UK human rights news agenda in the months to come.

Human Rights Act ‘Updated’?

This year, the government will assemble a “Constitution Democracy and Rights Commission” (CDRC), tasked with – among other things – proposing updates to the Human Rights Act 1998.

Why does this Act supposedly need “updating”? Well, according to the Conservative Party’s 2019 election manifesto, it is to “ensure that there is a proper balance between the rights of individuals, our vital national security and effective government”.

This position appears to mark a departure from the Conservatives’ previous pledge to scrap the Act and replace it with a so-called ‘British Bill of Rights’. But human rights lawyer Martha Spurrier, director of campaign group Liberty, has warned that the seemingly innocuous language of “updating” the Act is “far more sinister” that it looks.

Conservative leader Boris Johnson speaks at the launch of the Conservative Party manifesto in the 2019 general election. Credit: YouTube.

One of the updates announced by the government last year is to amend the Act so that it does not apply to issues that took place before it came into effect in 2000. The government claims this will protect British soldiers from “vexatious” legal claims over historic human rights abuses which took place namely in the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The accuracy of this claim has been called into question, as well as what this policy could really achieve – if anything – in practice.

It appears too soon to say what further changes will be made to the Act. But comments made by Boris Johnson following November’s London Bridge terrorist attack suggest protections are more likely to be watered down than bolstered.

The CDRC is also supposed to look at judicial review – the means through which the courts can assess the lawfulness of decisions made by public authorities, often in relation to human rights. The commission is to ensure it is “not abused to conduct politics by another means or to create needless delays”.

Among the rumoured proposals being discussed is to change the remit of the Supreme Court, according to an unnamed senior Conservative who spoke to website Guido Fawkes. This could see the court turning away from focussing on “cases of the greatest public and constitutional importance”, such as October’s hearing on the prorogation of parliament. Instead it could focus on “the most complex cases adjudicating tax and commercial cases”.

The CDRC’s proposals will not be considered by the government until after Brexit. But we will be eager to get answers to some of the following questions this year: Who will be on the commission? What are their records on human rights issues? How will they arrive at their recommendations?

Brexit: Workers’ Rights And Future Trade Deals

The EU and UK flags blow in the wind outside parliament. Image Credit: Christoph Scholz / Flickr.

Brexit, as you will have guessed, is to continue to raise numerous important issues in relation to our rights in the years to come.

A key one will be scrutinising how the government delivers on its promise to introduce a law that enhances workers’ rights post-Brexit. This promise was made after clauses pledging alignment with the EU on employment protections were removed from the Withdrawal Agreement Bill.

Another issue is the risk that vulnerable EU citizens could become undocumented and threatened with deportation if they do not meet the deadline to sign up to the settlement scheme (EUSS).

A third issue, among many others, will be the role that human rights plays – if any – in future trade deals that the UK strikes with the EU, or with other blocs and countries.

Data, Artificial Intelligence And Algorithms

Credit: Pixabay

From facial recognition technology to targeted advertising, the connection between tech and our human rights will only to become more significant in 2020.

Calls are growing for greater controls to safeguard ensure our human rights online. Big Tech companies are able to access huge amounts of information about you based on your browsing habits, information you’ve added to your social media profiles, purchases you have made online, your Google searches, and more.

This so-called digital revolution has given rise to privacy concerns. It is difficult to keep track of who holds what information on you, with consent agreements often lengthy and complicated.

This technology has also given rise to discrimination fears – as advertisers, be they companies or political parties, can use your data to micro-target messages to you on social media. It has been reported that some businesses have used this technology to ensure that only people of a certain age or race are able to see a particular job opportunity or housing advertisement.

Parliament’s joint committee on human rights last year called for a slew of reforms to safeguard our rights online: such as raising the digital age of consent to 16 and establishing an online database allowing citizens to see which companies hold on them. Could 2020 be the year we make inroads?

On a related note, the High Court may have ruled that the use of facial recognition technology by police is lawful last year – but the court’s ruling does not appear to have put the issue to rest. Ed Bridges, the activist who brought the case and claimed his privacy had been breached, has vowed to go to the Court of Appeal. Numerous watchdogs – such as the CCTV commissioner and Information Commissioner’s Office – have queried the lack of guidance around the use of this new technology.

It is not only people’s privacy rights that are being affected by tech. Human rights lawyer Philip Alston, the UN’s watchdog on extreme poverty, last year warned that the trend of governments digitising their welfare systems is undermining poor people’s rights to social protection and security. We are at “grave risk of stumbling zombie-like into a digital welfare dystopia”, he wrote in a report published in October.

The Limits Of The Right To Protest

Our right to protest is protected by Articles 10 and 11 of the Convention of Human Rights; however, these rights are qualified. This means public authorities can take proportionate steps to curtail them in the interests of public safety or to prevent interference in another person’s rights, among other reasons.

Be it in relation to the climate crisis, Brexit, or Donald Trump’s presidential visit, protest events are on the increase in the UK and this trend looks set to continue. It seems likely, then, that limits of the right to protest will continue to be tested in the year to come.

Last year saw the Metropolitan Police impose a London-wide ban on protests by Extinction Rebellion campaigners under section 14 of the Public Order Act. This move was later deemed unlawful by the High Court.

While earlier in the year the Court of Appeal upheld a public space protection order (PSPO), banning pro-life campaigners from protesting outside abortion clinics in Ealing. The High Court also ruled in favour of creating a permanent exclusion zone banning protests against LGBT+ inclusive lessons at a Birmingham primary school.

We will likely see developments in a number of high-profile protest cases in 2020. Among these is the case of the Stansted 15, protesters who stopped a flight – that was carrying migrants who were being deported – out of fear they would be persecuted. The group was convicted under counter-terror laws, but in August last year won the right to appeal.

Also included are the Preston New Road three – a group of anti-fracking protesters who received suspended sentences after being found to have breached an injunction restricting protests at a shale gas site in Lancashire. In December they appealed their conviction and challenged the “draconian” injunction, and now await a decision from the Court of Appeal.

Equality, Discrimination And Hatred

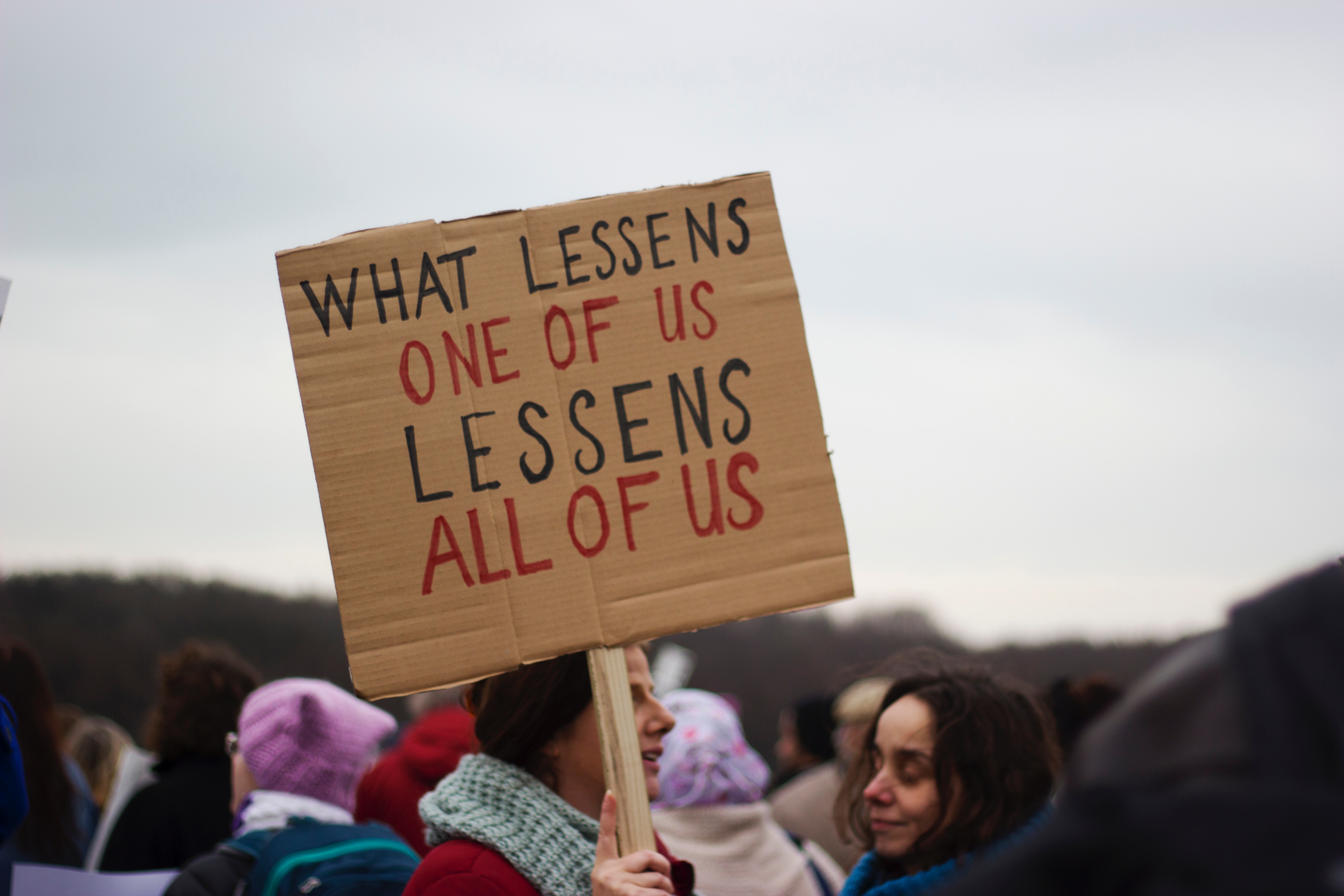

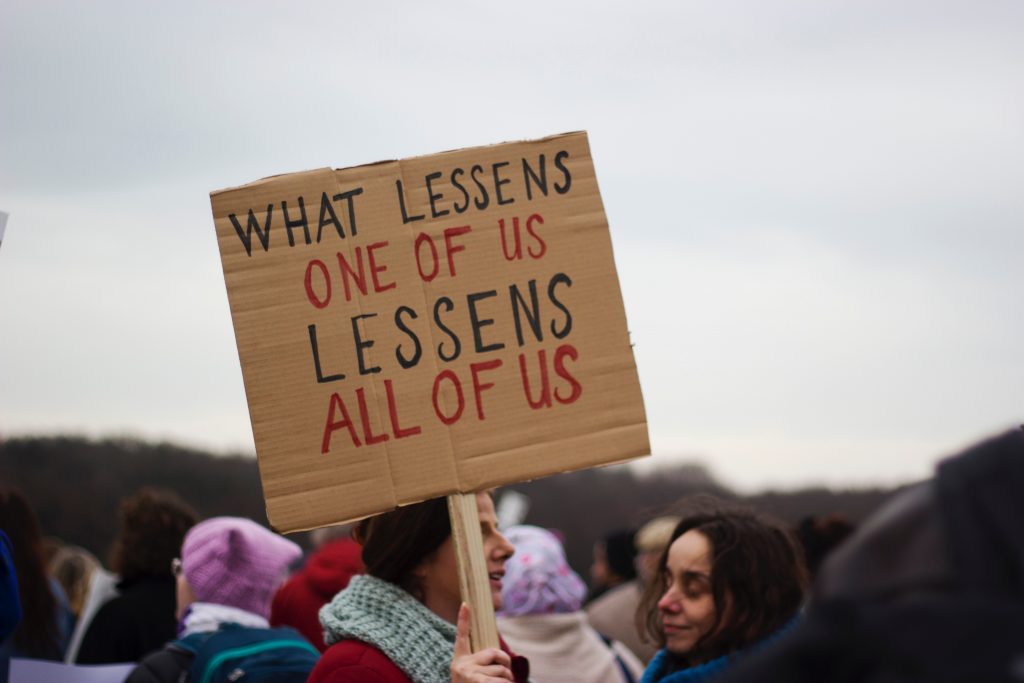

A protestor holds a sign saying “what lessens one of us, lessens all of us”. Image Credit: Unsplash

In 2019, we saw a number of alarming trends concerning the prevalence of bigotry and hatred in society at large. Reports of homophobic and transphobic hate crimes – including stalking, harassment and violent assault – more than doubled in the past five years, according to police data. Reported hate crimes against Muslims in the UK soared following the far-Right terrorist attack on mosque in Christchurch New Zealand in March. Anti-racism charity the Community Security Trust recorded a 10 percent increase in anti-Jewish hate crimes at the start of last year.

In 2020, we anticipate the fight to protect minorities’ right to live with dignity and to be free from discrimination will become even more important.

This year, we are likely to see the outcome of the Scottish government’s consultation on reforming the Gender Recognition Act 2004. The existing process for changing a person’s gender legally has been described as “overly complex and medicalised“, causing trauma and stress to those who go through it.

We may also see the outcome of the government’s consultation on granting police new powers to deal with trespassers who set up unauthorised caravan sites, which concludes in March. Campaign groups fear this law change will breach the rights of Travellers and Gypsies, by criminalising their centuries old way of life.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) is also expected to release its investigation into antisemitism in the Labour Party this year. The investigation, which was announced in May last year, will aim to determine whether the party has “unlawfully discriminated against, harassed or victimised people because they are Jewish”.

Meanwhile the EHRC is still determining whether it should also investigate the Conservative Party. It received a 20-page complaint from the Muslim Council of Britain more than six months ago concerning alleged Islamophobia.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has also promised to hold a separate inquiry into discrimination within the Conservative Party, led by professor Swaran Singh. The prime minister himself has faced accusations of Islamophobia after writing in a newspaper column last year that Muslim women wearing burkas “look like letter boxes”.

Sadly, this year we have already witnessed racist graffiti being spray painted near a south London Mosque, only a week after a north London synagogue was daubed with antisemitic graffiti.

There is no more time for inaction and no room for complacency.