‘How do we increase the number of non-white, disabled, female, or otherwise underrepresented, people working in journalism?’ That is the way discussions around media diversity are framed all too often. People might also talk about ‘changing the gatekeepers’ of key media organisations. Both of these things are important, but it is not why I campaign for increased media diversity and better representation.

I believe media diversity is important because I believe in human rights, and that idea was planted in me over 30 years ago when I was a teenager.

When I was 13 years old, a family friend was making a trip to Jamaica. I didn’t know it at the time but she was dying of cancer and she thought the UK was toxic for health and wanted to go “back home” to see if her condition would improve. As a parting gift to me she gave me a well-thumbed copy of the book “I Write What I Like” by Steve Biko. The book literally changed my life and still shapes how I view the world and specifically my approach to media diversity.

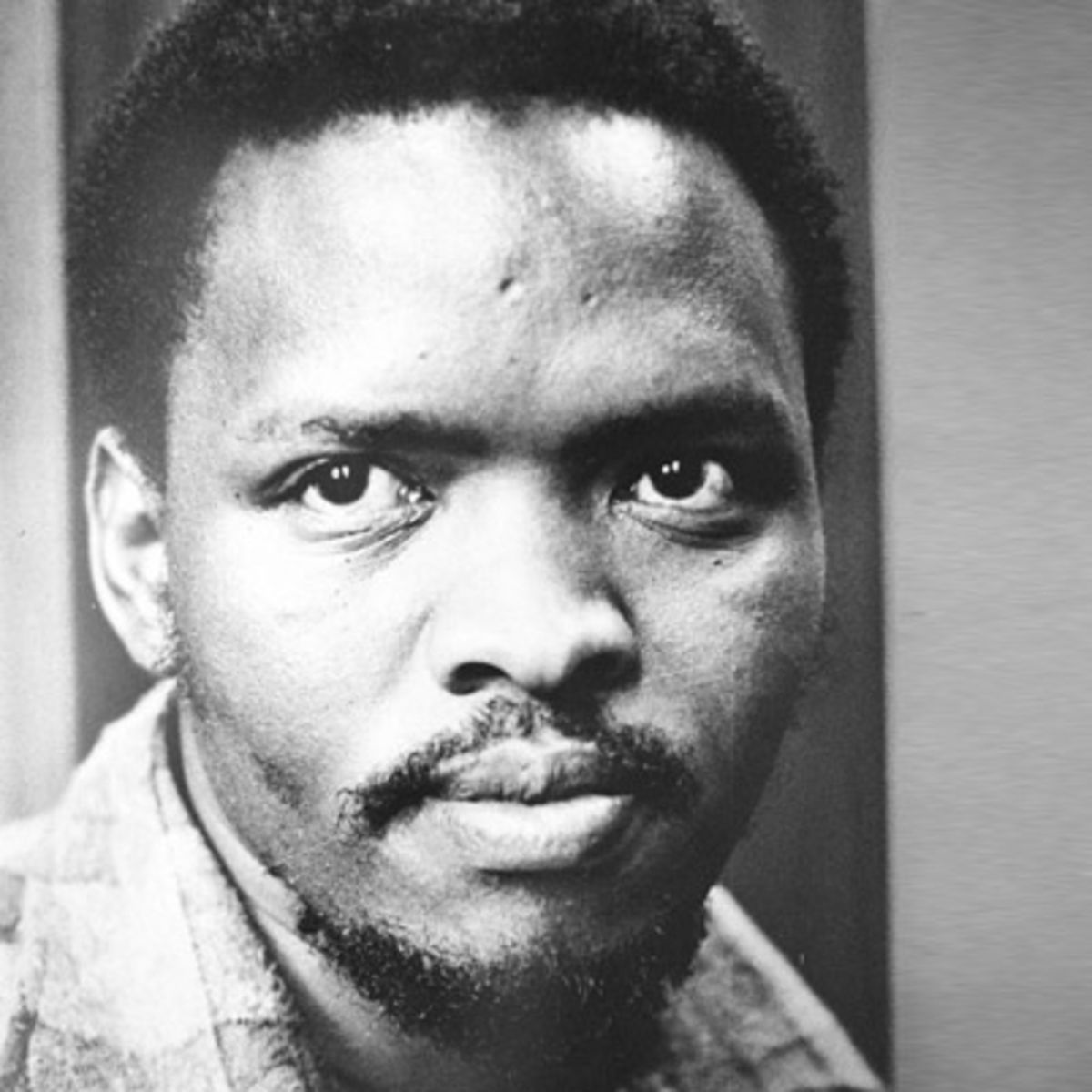

Marcus Ryder was inspired by black South African apartheid activist Steve Biko. Credit: Creative Commons / SA History Online

The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.

Steve Biko, I Write What I Like (1978)

Steve Biko was a black South African anti-apartheid activist, socialist and pan-Africanist who was beaten to death by the South African state security officers in 1977 for his opposition to the nation’s policies of racial segregation. The book, “I Write What I Like”, is a collection of his essays between 1969 and 1972 when he was president of the South African Students’ Organisation. Most importantly it articulated, and in many ways became the defining document of, the South African Black Consciousness Movement.

Possibly the most famous quote of the entire book is: “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

It is this one quote that beautifully sums up why media diversity is a human rights issue.

The media is how we share ideas, information, news and even culture. Whether that is through traditional journalism, drama, or even through dance videos on social media. And it is through this sharing of ideas, information, news and culture that our minds and beliefs are shaped.

Being able to write what we like is meaningless if we are not given access to the platforms to be able to spread that message.

Marcus Ryder

The way I interpret the title of Steve Biko’s book and his famous quote is – we need to be able to write what we like to ensure our minds, and lives, are not controlled by other people. They might not be our “oppressors” in terms of the apartheid regime at the time of Steve Biko’s writing but key to the Black Consciousness Movement was also a critique of white liberals. The “oppressor” was anybody who limited black thought and expression.

Being able to write what we like is meaningless if we are not given access to the platforms to be able to spread that message. And in talking about spreading that message, I do not mean being able to post something on YouTube or social media in the hope it goes viral.

Even videos or social media posts that are considered to have “gone viral” invariably do so with less than a million views. In contrast the popular British television soap EastEnders regularly attracts an audience of six million and it made national headlines when it temporarily dropped to two million due to a change in its time slot. BBC’s 10 O’Clock news attracts an average audience of over five million viewers.

So let’s unpack that for a minute.

The most popular television dramas which convey British culture and the most important news bulletins which tell us what are the most important news events concerning the country effectively “go viral” every day.

And here is the startling fact; black people specifically, and non-white people in general, do not have access to these types of mass platforms.

There is not a single major UK TV news bulletin with a non-white person in charge, that includes BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5. And in terms of drama, despite non-white people representing over 14% of the UK population, the number of non-white directors for EastEnders is around 2%. (I do not have specific figures for the number of black directors).

Only around 1% of directors on EastEnders are non-white, according to figures from Directors UK.

Now at this point I should point out that I am not apportioning blame or even trying to articulate why black people do not have access to these platforms (the reality is the reasons are multiple). But the end result is we do not have any black people with the final editorial decision as to what is and isn’t an important news event and we have very few black people, if any, deciding how British culture should be represented in our most watched television dramas.

It would be harder to think of how you would design a better system to fulfil Steve Biko’s quote.

And this is where it becomes a human rights issue that affects ALL human rights issues.

When I have given talks about this in the past, people are quick to understand the impact that effectively excluding certain sections of society from the most important media platforms has on free speech. But it goes deeper.

… Without a representative media not everyone’s human rights will be properly reported on and therefore protected.

Marcus Ryder

Let me give one simple example.

Take Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.”

It is argued the residents of the Grenfell Tower were denied this basic human right when the block burnt down on 14 June 2017. A lot of journalists also argued that one of the reasons it burnt down is because predominantly white newsrooms did not think the known safety concerns were important enough to report on before the fire and therefore the issues were never taken seriously by the policy makers who could have addressed them.

It takes only one more small step to conclude that the 71 people who died in Grenfell were denied the most basic human right – Article 2, the right to life – because of the lack of media diversity.

This one example shows that without a representative media not everyone’s human rights will be properly reported on and therefore protected.

If we care about our human rights we must all fight for media diversity.

That is why I am honoured to be part of the Black Lives Matter takeover this week and, to echo the words of Steve Biko, I hope we can all do our little bit to ensure we can control our minds by ensuring representation in who controls the sharing of ideas, information, news and culture.

I look forward to an important and exciting week of reshaping how we discuss media diversity.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.