Today, on Human Rights Day, EachOther launches ‘Excluded’ – a film amplifying young people’s voices on the issue of school exclusions. Creative Director Dr Sarah Wishart offers a behind-the-scenes look at how this documentary with a difference was created.

Article continues below.

The journey behind ‘Excluded’ starts in early 2018. I had been talking to schools across the UK who had signed up to Unicef’s Rights Respecting Schools initiative – which seeks to embed children’s rights in daily school life – for a film the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) commissioned us to make.

Early on in the project, it was clear to me the project should be child-led. And through primary school pupils’ conversations, we demonstrated how simple it is to understand human rights:

Children have some excellent and honest opinions on human rights. Watch the full video by @rights_info and @EHRC to see what these adorable children from Unicef UK’s Rights Respecting Schools have to say: https://t.co/2an3hzNQXK #FairPlay pic.twitter.com/SdMfCagQCn

— Unicef UK (@UNICEF_uk) May 24, 2018

As the young people at these schools shared their views with us about the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, one right in particular stuck with me: Article 12 – young people’s right to be listened to.

As an organisation, we are always looking for ways to talk about human rights that spark conversations and connections – and I felt sure there was a bigger project here for us around rights and education.

Later that year, I found my inspiration.

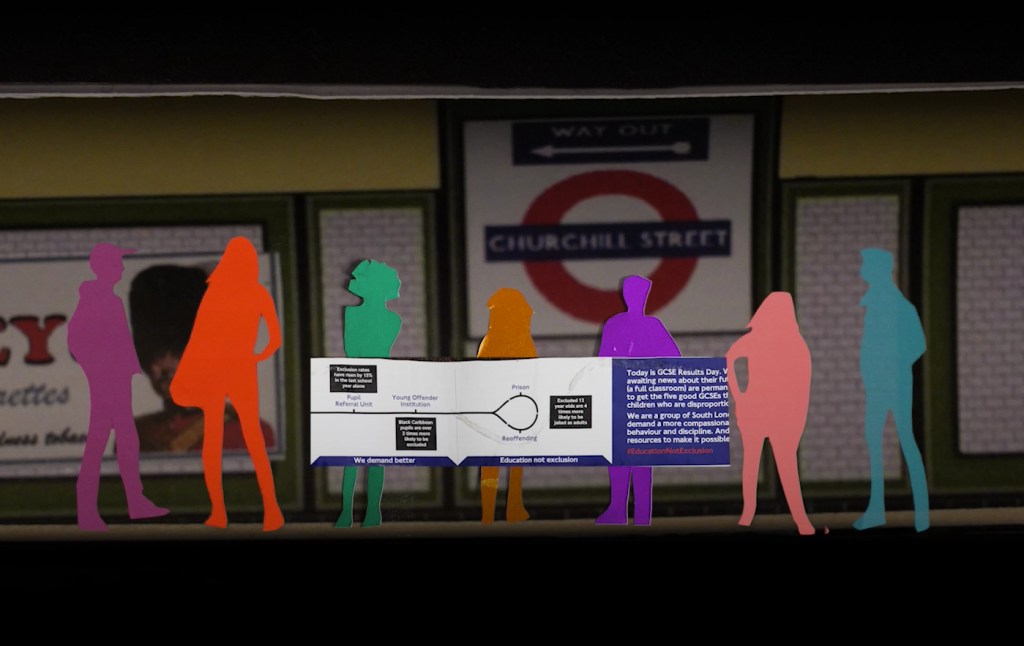

On GCSE results day 2018, I saw the early morning Twitter storm created by young people from the campaign group ‘Education Not Exclusion’, who had undertaken a protest action on the London Underground.

Brilliant ad-hack showing how exclusion sets young people on the school to prison line . It impacts black, brown and poor white students. I would go beyond the ask and call for funding for education alternatives to mainstream schooling and education reform #educationnotexclusion pic.twitter.com/NPZ89ZtWZa

— Deirdre⭐Dee⭐Woods (@Didara) August 23, 2018

Overnight they had replaced the maps of the Northern Line with a poster, in the same shape and branding, which sought to draw attention to the common path that leads many expelled pupils to end up in prison.

(Still from our film ‘Excluded’, © EachOther 2020)

They highlighted how exclusions are fundamentally a human rights issue. When you exclude a young person from school, you interfere with their right to education. But this is rarely the only human rights violation they face. Excluded young people are also at risk, for example, of being drawn into serious youth violence – as both victims and perpetrators – are overrepresented in the prison system and often have their home life and private life disrupted.

Initial filming for Excluded started as a passion project. We didn’t have specific funding for it and so it progressed slowly. We’d film chunks when we had a gap in our project work.

We began in early 2019 at a Basingstoke Pupil Referral Unit – an alternative schooling centre designed as a last resort for children who cannot cope in a mainstream school.

Cody, 12, a student at Ashwood PRU in Basingstoke. (Still from our film ‘Excluded’, © EachOther 2020)

Then, in the summer, we were introduced to a number of young people, including the campaign group ‘No Lost Causes’. This group had picked up the baton from ‘Education Not Exclusion’ – taking their awareness raising campaign around the school-to-prison-pipeline to Robert Halfon MP, the chairman of Parliament’s Education Select Committee. One young woman I met that day, Betty Mayo, was so fired up by the project, she came on board with us as a researcher and drew our attention to the Nurture programme in Glasgow. This programme is credited with having reduced exclusions in the city dramatically.

Betty Mayo, 21, (Still from our film ‘Excluded’, © EachOther 2020)

… We wanted to make a different sort of film. In a different sort of way.

Betty Mayo

Then, in October, I was asked to speak at the School Exclusion Summit at east London’s Leyton Sixth Form College, where I met two young people – Kadeem and Jordane. Their experiences of being excluded feature in our film.

So much discussion around school exclusions comes from policymakers and teachers, think tanks and youth workers. While we wanted those voices to surround the film in articles and interviews, I wanted the film to offer a platform for those most affected – young people – to share their thoughts, their solutions, their ideas, their experiences. And I wanted them to shape the way our film was made, and for this to be as important as the film’s content.

Kadeem, 26, was first excluded in primary school at the age of seven. (Still from our film ‘Excluded’, © EachOther 2020)

At the end of 2019 we got some funding and we were in a different space and able to pay young people for their time on the project. I was also able to bring filmmaker Anna Merryfield on board, with her experience with collaborative participant-led projects. We set up workshops with young people in London and our next batch of filming with youth and family support charity Includem in Scotland.

And then lockdown happened.

Not wishing to lose momentum, we held the workshops online – a bit of a technological challenge but we learned fast – like everyone else. We listened the young people’s views on what kinds of audiences they wanted the film to reach; whether they thought we were missing any stories or perspectives; and what issues they felt we needed to include. And we sent audio recording equipment to young people around the country so that they could record their own stories, even though we couldn’t film. Anna and I wanted to find out not only what they wanted to tell us about their experience, but how they wanted to be represented – even if they wanted to be anonymous or didn’t want us to film them on location. I worked with graphic artist Jon Sack to ensure we followed their directions on how we should portray them in illustrations.

Beth (not her real name) is among the young people from charity Includem who shaped our documentary ‘Excluded’. (Illustration: © Jon Sack)

The stories that came back were really hard to hear, but vital for us to listen to. Among them was that of Glaswegian apprentice joiner Beth, 20, who opened up about her experience of unbelievable trauma and grief at the age of 12, and how she would later go on to be temporarily excluded from school. Another is that of college student Ewan, 14, who felt hounded out of school because he’d been labelled as irredeemably disruptive. All the experiences in the film bear many similarities. But what also struck me, time and time again, was how much their solutions echoed those included in an ever-growing list of reports by think tanks, MPs, charities, and others on how to fix the problem.

They also wanted to foster empathy: for people to understand that issues they were facing outside school were inevitably going to have an impact on them in school. They were empathetic in turn about the challenges teachers have faced under austerity. But they also spoke about how treating excluded pupils with low-expectations would create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Hearing from these young people made us realise just how many different experiences of exclusion there are, and how many different groups of people are affected. While our film includes wide-ranging perspectives, it would never be possible to cover every viewpoint from all corners of the UK. But we have been able to give a platform to stories that have never before been heard, and we will be focussing on this issue into the next year.

It has been a privilege to make this film and to give the floor over to these voices. I would like to thank all the young people for trusting us with their stories. We want the film to be used to start conversations. We start the next bit of that journey tomorrow – when Betty Mayo and Natalia Morgan who feature in the film join us for our live stream panel discussion with Glasgow City Council’s Maureen McKenna and the Director of The Runnymede, Dr Halima Begum.