For many of us, if we’re lucky, the law rarely crosses our minds. At least that may have been the case until the pandemic started, with ever-changing curbs now placed on our lives to try and prevent deaths.

Whether we realise it or not, legal issues touch on all aspects of life: from intimate family matters to society’s biggest issues.

But evidence suggests many of us are “dangerously” unfamiliar with how the justice system works.

In November last year, a poll revealed that more than one third of Britons do not know the difference between civil and criminal courts.

More recently, lockdown sceptics on Twitter have falsely claimed that placing a copy of Magna Carta – “the Great Charter of the Liberties” accepted by King John of England in 1215 – in a shop window will grant a business legal immunity from shutting under the national restrictions set to come into effect on Thursday.

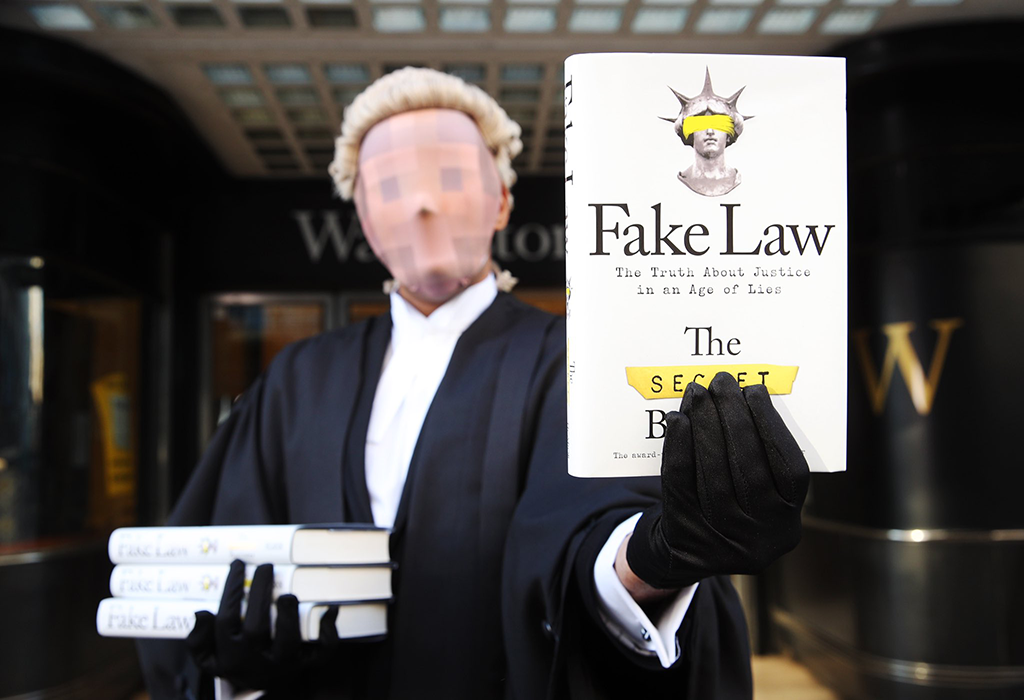

This false theory was quickly put to bed by legal experts, among them the Secret Barrister (SB) – who is arguably the country’s most famous lawyer, and whose identity and gender remain under wraps.

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT:

THINGS THAT DON’T GIVE YOU LEGAL IMMUNITY FROM COVID REGULATIONS:

❌Pinning Magna Carta in your pub window

❌Declaring yourself to be an independent nation

❌Dressing up as a spitfire

❌Stapling a photo of the Queen to your buttocks

— The Secret Barrister (@BarristerSecret) November 2, 2020

SB is worried about this lack of public knowledge, which is said to stem partly from the fact the law is inherently – and often unnecessarily – complicated. It leaves us vulnerable to misinformation peddled by vested interests and allows for the abuse of our laws, rights and democracy, it is argued.

Among the protections it is feared the government will soon water down is judicial review – which enables people to challenge public bodies’ decisions if they feel they’ve been treated unfairly – as well as the Human Rights Act.

SB’s latest book, Fake Law, seeks to debunk these areas of our legal system, among others, said to be common targets of myths, lies and spin.

Separately, SB has warned the pandemic could deliver the final blow to our justice system on the verge of crisis following years of chronic underfunding.

We spoke to SB to find out more on the threats to our laws, the impact of the pandemic, their hopes for the future and plenty more.

The Secret Barrister answers EachOther’s questions. Credit: Channel 4

I think that lived experience is the best remedy for ignorance.

The Secret Barrister

When was the last time you changed your mind about an important issue?

Oh gosh. There’s plenty. Most of what I believe now about the justice system is the polar opposite of what I believed in my 20s. Seeing criminal justice in action, as opposed to simply reading uninformed opinion in the press, blew my mind open.

Just one example – criminal sentencing. I entered the profession believing what I had read my whole life about lily-livered judges handing down ridiculous sentences to crooks in service of a secret liberal judicial agenda. The reality, you quickly learn from watching the courts in action, is that there is almost always a good reason for a judge imposing particular sentence, and it is rarely as straightforward as reflected in the press. I think that lived experience is the best remedy for ignorance.

You can’t guarantee that you will always (if ever) be the best lawyer in the room, but it is within your power to be the kindest.

The Secret Barrister

What is the most important lesson you have learned in your time as a barrister?

You can’t guarantee that you will always (if ever) be the best lawyer in the room, but it is within your power to be the kindest. The criminal courts are hubs of stress and chaos, and everyone is just trying to keep the train on the rails. Remembering that you are all in it together, and treating everybody with courtesy and kindness, is a lesson drummed into me by wiser heads, and is the one that I hope I always put into practice.

British comedian John Oliver on Last Week Tonight. Credit: YouTube

What was the last thing that made you laugh?

John Oliver on Last Week Tonight. I can’t believe we let America steal him. His country needs him.

What is your favourite piece of feedback you’ve received so far about your new book Fake Law and why?

There have been some lovely reviews, but my personal favourites would be messages from members of the public who have got in touch to say that the book has changed their perspective about one of the topics covered. That’s really the whole point – to try to help people see through the misinformation and identify where the truth lies.

What is the biggest challenge you have faced as a result of being anonymous?

Maintaining anonymity is of course its own challenge; the constant low-level anxiety that I’m only a day away from everything tumbling down around me. But the one thing that I would like to do, that I can’t, is more broadcast work. I have to turn down almost every offer, which restricts my means of communication to the written word. I love writing, but to reach a wider audience you need to be in their faces and down their ears. So to speak.

Which other ‘cog’ within the wider justice system would you most like to hear anonymously share their unfiltered perspective on its challenges and why?

I think every cog has its own fascinating insight into the operation of the system. I’m currently reading The Secret Magistrate and enjoying it very much.

If you could immediately put right one problem in the criminal justice system, what would it be and why?

I would open enough courts to deal with the backlog. Civic centres, theatres, cinemas, court centres recently sold-off by the government – I’d hire them all and open the hundreds of Nightingale Courts that we need so that people aren’t waiting years for their trials. Once the backlog was under control, I’d look into ensuring that increased court capacity was permanent, and introducing time limits by which trials should be held.

What one issue worries you most about how the justice system has been affected by the pandemic?

The backlog. The government has chronically mismanaged criminal justice, and the political decision to starve the criminal courts of sitting days prior to the pandemic is one of the most short-sighted and damaging decisions in recent years. It meant that the courts were uniquely badly placed to withstand the sort of pressures that Covid has brought to bear, and the government’s complete failure to do anything in the first six months of the pandemic to get jury trials back up and running at full capacity means that we now have standard delays of years built into almost every Crown Court trial.

What is your view on the government’s plans to ‘update’ the Human Rights Act (HRA)?

This is a government which loathes accountability, and has demonstrated repeatedly its contempt for the rule of law and the judges and lawyers who work to uphold it. Any ‘update’ to the HRA will amount to a strengthening of the executive’s hand at the expense of the citizen.

Are there any valid ways you feel the HRA could be improved?

I am sure that practitioners in the field could offer many sensible recommendations, but ‘improving’ the HRA is not the motivation behind the ‘update’. The aim is dilution or removal.

What is your view on the government’s ‘review’ of judicial review?

As with the HRA, the ‘review’ was a fait accompli even before the announcement of the Chair (former Chris Grayling right-hand man and outspoken opponent of Judicial Review, Edward Faulks). It is an exercise in chipping away at public faith in the judiciary and eroding executive accountability.

What is the most important human right to you and why?

Article 6 – the right to a fair trial. Without this, without access to justice, all other rights are rendered nugatory.

In recent years, there have been numerous campaigns to reform our criminal laws in various ways, some of which are addressed in your book and recent media commentary. Among them are calls to ban ‘rough sex’ defence, to scrap jury trials in rape cases, to introduce tougher sentences for those convicted of killing emergency service workers, and calls to legalise and regulate drugs. Is there any such initiative which you are most persuaded by and, if so, why?

For my part, having seen the ruin wreaked by prohibition, I would be in favour of a serious review of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, with a view to, if the evidence supported it, a move towards a system of decriminalisation and regulation of controlled substances.

Conversely, is there any one of these initiatives which worries you most and, if so, why?

Any campaign which is based on the premise that we need to make it “easier” to convict people makes me nervous. Removing juries or changing the standard of proof in criminal trials are ideas that recur every few years, and these ideas trouble me. I fully understand the reasons behind public concern with, for instance, prosecution rates in cases involving sexual violence.

The figures are shocking and reflective of a system which is simply not working. However, the analysis that assumes that the solution lies in loading the trial process against the defendant is one that troubles me.

The problem is complex and multifaceted, and the solution lies outside the law in education as much as within the law.

The Secret Barrister

The problem is complex and multifaceted, and the solution lies outside the law in education as much as within the law, but certain steps can be taken that would immediately improve the quality of justice for victims.

For example, improving and resourcing investigators; reducing delays so that complaints are charged are brought to court more quickly; cutting the court backlog so that people don’t wait years for trials; properly funding forensic science services and Rape Crisis Centres and requiring juries to give reasons for their verdicts.

This would enable us to see whether they are working as they should – there is a lot that I think we should be demanding that the government address before we start removing individual rights.

Legal commentator Joshua Rozenberg QC. Credit: YouTube

As you outline in your book, the rule of law is under threat. As one solution, you propose separating the role of Lord Chancellor, charged with safe-guarding the independence of the judiciary, from the partisan role of Justice Secretary. If you could pick anyone to be the Lord Chancellor, who would it be and why?

Either Joshua Rozenberg QC or David Allen Green. Both exceptional lawyers and commentators, with a formidable understanding of the importance of the rule of law and impeccable independent judgement.

What one piece of advice would you give to journalists, be they cub reporters or seasoned hacks, to ensure they report on the law accurately and truthfully?

Ask questions. If a story about the law – be it a verdict, sentence or legal aid story – seems too ludicrous to be true, it almost always is. Ask a professional what has gone on in that case, what the likely explanations are, what the law actually says and, crucially, why the system works in that way. You’ll not only avoid contributing to public misunderstanding, but will happen across the very real – and far more interesting – problems with how we do justice.

In an age where people are fed up of being lied to, I think there’s a market for truth.

The Secret Barrister

What, if anything, gives you hope for the future?

I think that there is a growing public appetite for information about the justice system. A decade ago, books by a barrister droning on about how the legal system works would have been a non-starter for any mainstream publishing house.

Now you can’t turn around in Waterstones without smacking into a popular book educating the public about justice – whether it’s Sarah Langford or Jon Robins or Alexandra Wilson or Chris Daw or Colin Yeo or Joshua Rozenberg or one of the many, many brilliant legal writers whom I will kick myself for omitting the second I’ve finished answering this question.

In an age where people are fed up of being lied to, I think there’s a market for truth. That gives me real hope.