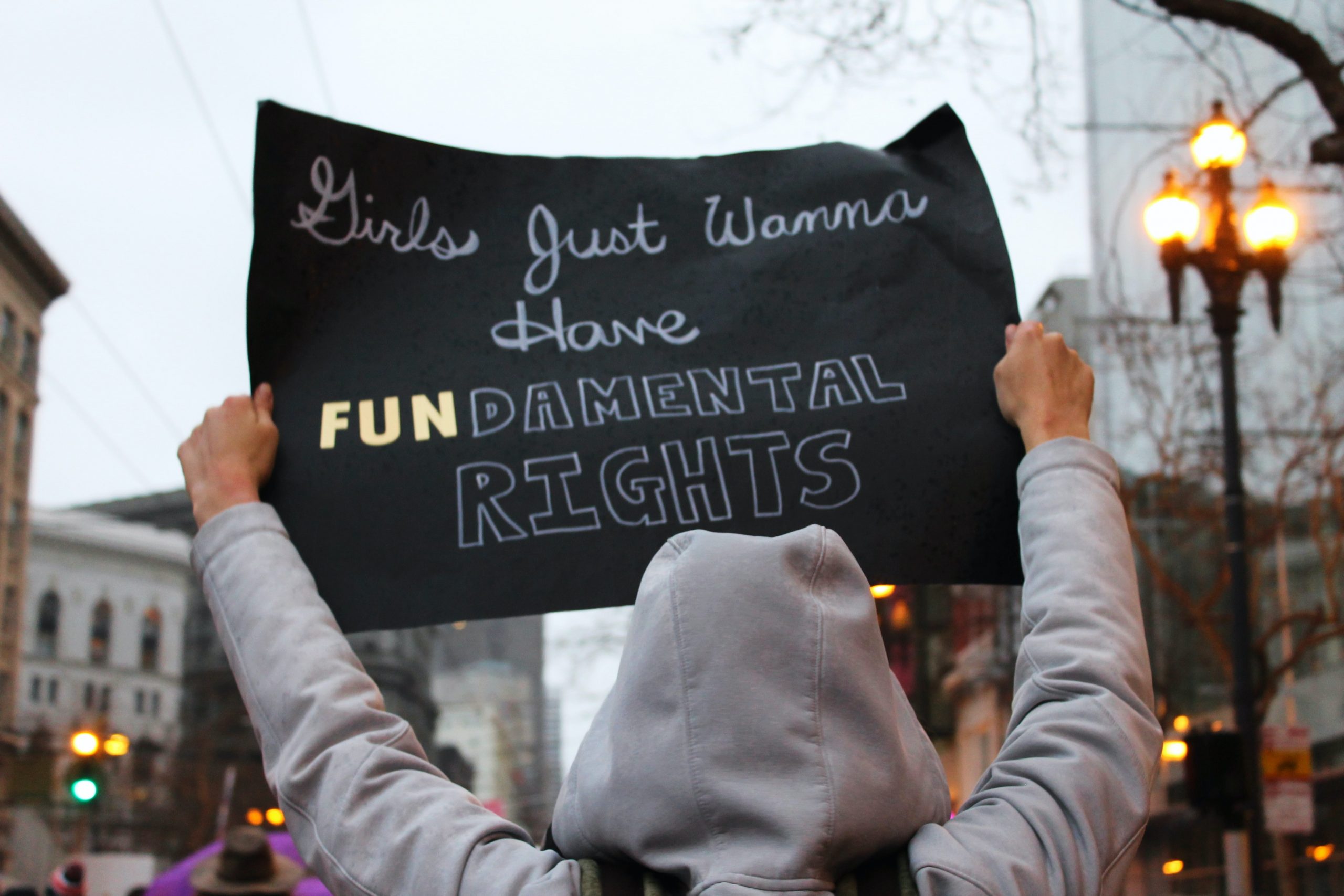

Throughout 2021, EachOther reported on human rights issues across the UK, including those affecting people on account of their characteristics protected under the Equality Act. To usher in the new year, we are highlighting the issues that are particularly affecting five such groups in UK society, looking forward to the opportunities 2022 might afford and the challenges the year ahead might pose. In this mini-series, we focus on these five of the nine protected characteristics in the Equality Act: race, sex, sexual orientation, disability and religion.

Since the 1970s, dedicated legislation has sought to protect people living in the UK from discrimination on the grounds of their sex or gender. This includes the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, later replaced by the Equality Act in 2010, and the Gender Recognition Act 2004.

These legislative changes have been instrumental in protecting people from abuse based on their gender. But, as we reflect on 2021 and look ahead into 2022, there is still much more work to be done.

How were the rights of marginalised genders affected in 2021?

Credit: Seven Shooter / Unsplash

For women and girls, the history of discrimination is a long one. In the UK, all women, at last, won their hard-won right to vote in 1928, thanks in part to the suffrage movement, but legislation enshrining the right to receive equal pay was not introduced until 1970.

Still, the gender pay gap persists, showing that some women are paid less than their male counterparts for the same work. Despite narrowing by around a quarter in the past decade, it currently stands at 7.9%.

Violence against women and girls remains rife in the UK. In March, the abduction, rape and murder of Sarah Everard prompted public outcry, as thousands of women and girls across the country spoke out about the abuse to which they have been subjected. Later that month, a survey for UN Women UK found that more than seven in ten women had been sexually harassed in public, a figure rising to 86% for women aged between 18 and 24.

People of marginalised genders are increasingly being subjected to gender-based violence and harassment. Hate crimes against transgender and non-binary people quadrupled from 598 in 2014-15 to 2,588 in 2020-21, according to one report by VICE World News. Despite this, calls to make misogyny a hate crime have been repeatedly dismissed by the government.

Men in this country can also face discrimination and inequalities. In February last year, a survey carried out for the charity Mankind UK found that half of men have had unwanted sexual experiences. When it comes to mental health, men are around three times more likely to take their own life than women in the UK.

Women and Girls

Credit: Michelle Ding / Unsplash

In the wake of Sarah Everard’s rape and murder, women and girls across the country shared their stories of violence, sexual assault and harassment, including thousands of testimonies on the website Everyone’s Invited. These testimonies named hundreds of primary and secondary schools as locations where this abuse had occurred, alongside 119 universities.

Susie McDonald, director of the charity Tender, works to help prevent domestic and sexual violence in the lives of young people. Going into 2022, she says that the introduction of compulsory relationships and sex education in schools in England in 2020 has presented the “perfect opportunity for the school environment to become a place where these difficult issues can be talked about, where young people can learn about them in a really well-rounded way”.

Still, a lack of government support is reducing the ability of teachers to address sexual violence and harassment in schools. “There’s been very little financial investment into training for teachers to feel confident about teaching that curriculum, let alone devising it for their individual schools,” she explained. “So I’ve seen examples of very poor practice. And I’ve heard a lot of anxiety amongst teachers about how on earth you talk about unhealthy relationships with your student population.”

Going into 2022, Tender will continue to support schools to help prevent abuse among young people, including through its programmes with schools and universities.

“The really key thing is about holding accountable the behaviour of mainly boys and young men around sexual harassment,” McDonald said. “What there isn’t at the moment is Department for Education or government guidance on how schools should be managing and dealing with perpetrators of sexual harassment.”

Credit: Dario Valenzuela / Unsplash

There are also growing calls for increased support for women facing mental health problems. Last year, a joint investigation by EachOther and openDemocracy found that women were disproportionately affected by mental health detentions during the first Covid-19 lockdown – with a 25% rise in some parts of England.

For Joyce Kallevik, director of Wish, a women’s mental health charity, there is concern surrounding the police involvement with women experiencing mental health crises. Wish is supporting a campaign by StopSIM against a model of care known as Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM), currently used in 23 out of 52 NHS trusts. The group believes this method, which unites the police with mental health services, breaches rights enshrined in the Human Rights Act and the Equality Act.

“The thing we are most concerned about is the huge amount of criminalisation of distress, with many people arrested or charged for repeatedly attempting suicide or showing up at A&E and an increasing amount of police involvement in mental healthcare,” said Kallevik.

“Though this has happened for both men and women, we personally have seen women who have a diagnosis of ‘borderline personality disorder’ the most affected. It is a highly stigmatised diagnosis and these kinds of initiatives only stigmatise more, insinuating that women’s distress is not legitimate and merely a way of ‘seeking attention’.”

Ultimately, it takes those in powerful positions to dismantle gender inequality in our society, says Carey Philpott, head of communities at SATEDA, a domestic abuse charity.

“We need men and people in positions of power to dismantle the systemic gender inequality and cycles of coercion and control within their institutions which is mimicked in gendered violence,” said Philpott. “We need them to name misogyny, systemic gender inequality, toxic masculinity, rape, femicides, and coercive control, and we need them to understand that male violence against women and girls is at epidemic levels and happens in a context of patriarchy, fuelled by sexism and misogyny which goes unreported and unchallenged.”

Transgender and Non-Binary People

Credit: Oriel Frankie Ashcroft / Pexels

Against a backdrop of rising transphobic hate crime, campaigners working to advance the rights of transgender and non-binary people are calling on the government to make a number of changes in 2022.

In December 2021, a report by the Women and Equalities Committee (WEC) found that the government had failed to adequately respond to its own consultation on reforming the Gender Recognition Act a year earlier. A report published by the committee criticised the current process for being “unfair and overly medicalised,” and called for urgent reforms to be made.

The report has reignited calls for the Act to be reformed, including by the trans-led charity Gendered Intelligence. In December, Gendered Intelligence also supported the Good Law Project as a claimant in calling for a judicial review into NHS England over their commissioning of gender identity services, including the long waiting times involved with gender-affirming care. Some transgender people have had to wait up to three years for their first appointment at a gender identity clinic.

Last year, the charity was a claimant in a case led by the Good Law Project to successfully overturn a judgement known as Mrs A and Bell v Tavistock, which had ruled that children under the age of 16 were unlikely to be competent enough to give informed consent to puberty blocker treatment. The overturning of the High Court decision was hailed as a major win among transgender rights campaigners.

“The broadly negative media climate regarding transgender people and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the LGBTQ+ community made [2021] difficult for the trans community,” said Cleo Madeleine, communications officer at Gendered Intelligence.

“However, progress has been made in the legal fight for our rights, and the WEC recommendations are welcome. We will continue working with organisations like the Good Law Project to ensure that the voices of trans people are heard, and that progress towards justice is made.”

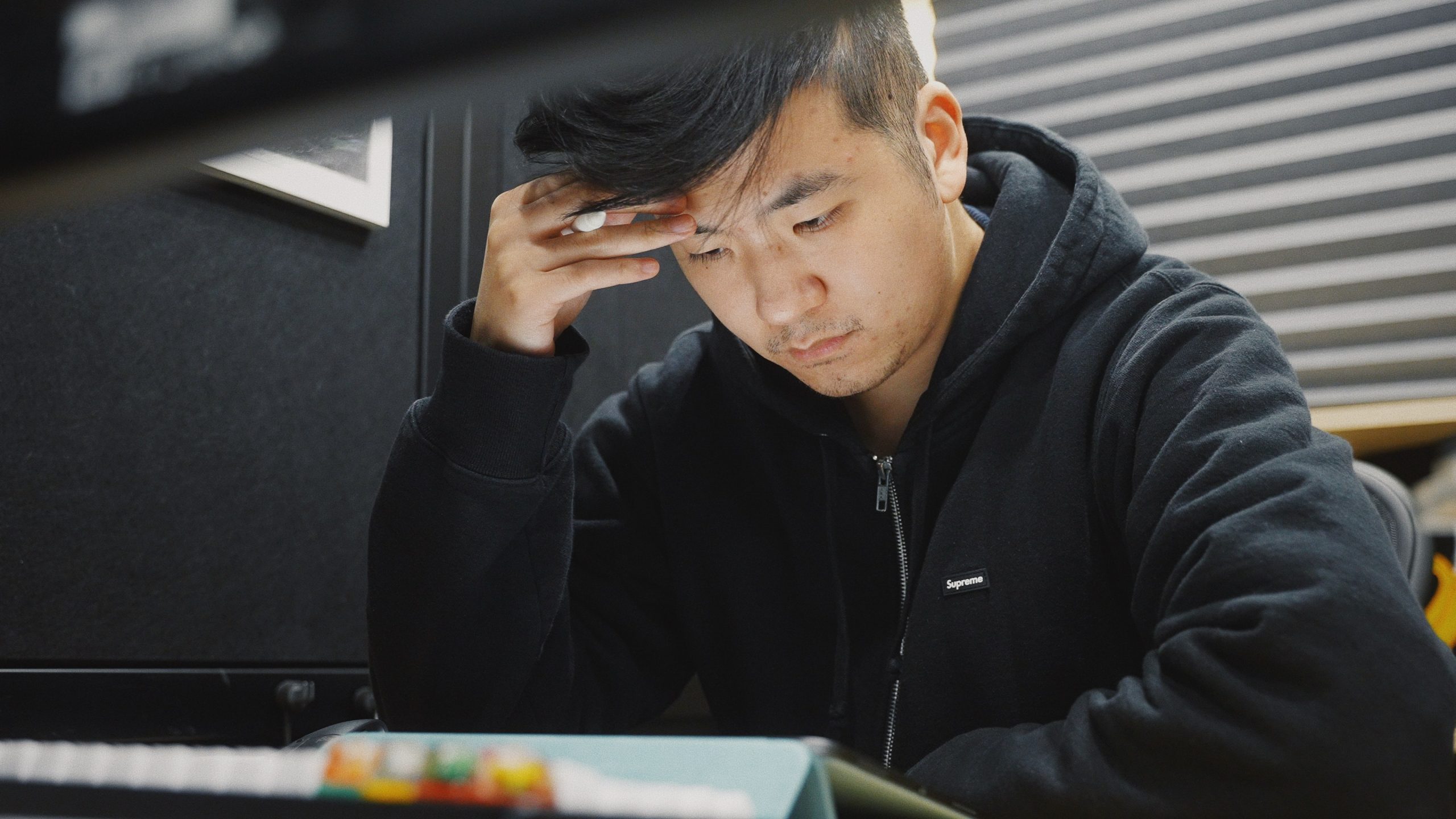

Men

Credit: Barney Yau / Unsplash

For men in the UK, mental health remains a major issue and is the focus of a number of charities this year. In 2020, around three-quarters of registered suicide deaths were for men (3,925), in line with a consistent trend dating back to the mid-1990s, according to data from the Office for National Statistics.

One 2020 report by suicide prevention charity Samaritans found that men aged between 40 and 59 experienced the highest suicide rate of any age group over the past two decades.

“Society’s expectations and traditional gender roles play a role in why men are less likely to discuss or seek help for their mental health problems,” reads an article on the Mental Health Foundation’s website. “We know that gender stereotypes about women – the idea they should behave or look a certain way, for example – can be damaging to them. But it’s important to understand that men can be damaged by stereotypes and expectations too.”

Despite these bleak figures, charities and individual campaigners are working to end the stigma against men speaking about their mental health. One Country Durham man has already raised hundreds of pounds for a local men’s mental health club as he walks up to five miles a day while taking part in Dry January. And, in Warrington, weekly football sessions are raising awareness of men’s mental health.

Rights abuses affect people of all genders and, while some incremental progress has been made in the past year towards improving awareness of violence against women and girls, a lot of work still needs to be done before everyone’s rights are equally protected.

—

If you are in the UK and are having suicidal thoughts, suffering from anxiety or depression, or just want to talk, you can call the Samaritans helpline on 116 123.