A new Bill has been tabled to help the government return asylum seekers to “safe countries” in an effort to reduce the number of people claiming asylum in the UK.

Introduced by Conservative MP Peter Bone, the Asylum Seekers (Return to Safe Countries) Bill has passed its first reading and is due to face its second on 3 December.

The Bill would “require asylum seekers who have arrived in the United Kingdom from a safe country to be immediately returned to that country”. This could apply to those arriving directly from countries deemed “safe” by the UK or to asylum seekers arriving in the UK via a safe country such as France or Germany.

“The Asylum Seekers (Return To Safe Countries) Bill seeks to return any asylum seeker who has arrived from a safe country – France or another EU country – to that country,” explained Professor Siraj Sait, director of the Noon Centre for Equality and Diversity at the University of East London. “In addition, the Bill seeks to send messages to France and others that it will not receive illegal migrants coming from there, as well as a deterrent to migrants who choose the UK as a destination.”

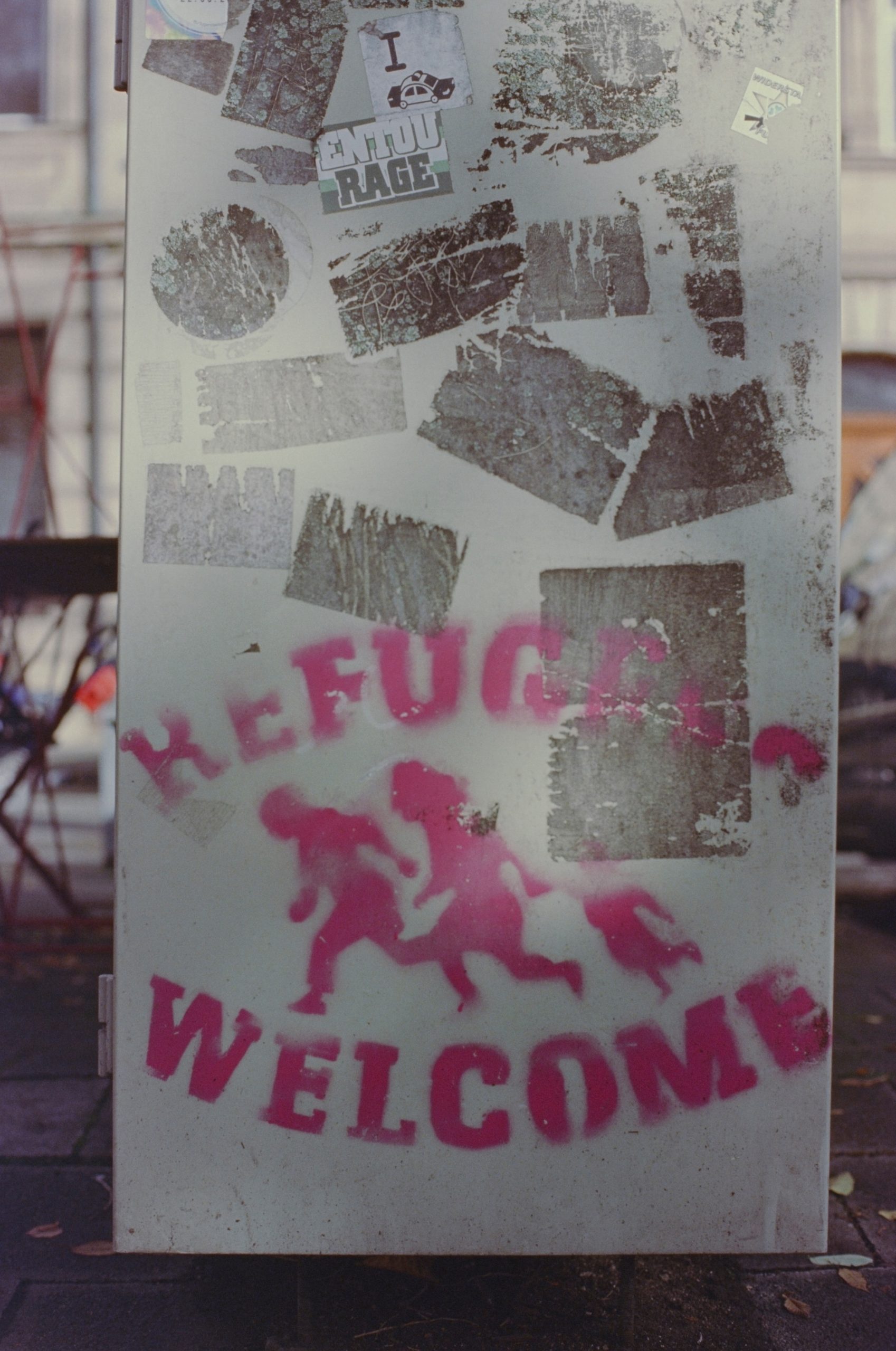

Credit: Markus Spiske / Unsplash

There is some concern that the Bill could threaten protections set out in the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, which the UK played a crucial role in drafting. Under the Convention, refugees are not required to claim asylum in the first safe country they reach, nor does the Convention make it illegal to seek asylum if they pass through another safe country first.

“This ‘first safe country’ is not a principle of international refugee law,” said Sait. “The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has raised concerns about these bills saying it undermines the 1951 Refugee Convention, which the UK has obligations under. Thus, UK actions are being criticised by advocacy groups as being inhumane and illegal as they put at risk the lives and well-being of vulnerable people by denying their right to seek asylum from persecution.

“When an asylum seeker is sent back to another safe country, the UK cannot be sure that through a chain of deportations it has initiated, the asylum seekers will not be returned to unsafe countries.”

Although asylum seekers do not have free reign to select their country of asylum, many choose a specific country based on pre-existing connections, such as family links.

The UK is in the midst of a complete overhaul of its immigration systems with its “New Plan For Immigration” and the Nationality and Borders Bill (NABB) going through the committee stage in the House of Commons.

Credit: Christian Lue / Unsplash

Credit: Christian Lue / Unsplash

Critics, however, have argued that a stricter approach to immigration and asylum seekers is a disproportionate reaction to the numbers the UK actually receives. Globally, there are about 26 million refugees and 86% of them live in lower or middle-income countries, while 73% are hosted by States neighbouring their countries of origin. The UK saw 29,456 asylum applications in 2020, compared with 95,600 in France and Germany’s 122,170.

“The benefits of implementing the Bill would be to cut down the number of asylum seekers from France. However, there is no guarantee that the bill, if it becomes legislation, would lead to France taking back asylum seekers,” added Sait. “Before Brexit, the EU’s so-called Dublin Regulation ensured that arrangements for the return of asylum seekers worked. Now, it is a political standoff between the UK and France. The risks of the Bill are that asylum seekers will be caught in between, and unable to secure protection and their human rights under international law.”

According to the UNHCR, “the number of resettlement places offered by states, though important, pales in comparison to needs.” Over four years, UNHCR has resettled an average of 51,828 refugees per year globally, set against approximately 1.4 million people who require asylum. Due to the fallout of the pandemic, only 22,770 were resettled through UNHCR in 2020, with 829 being placed in the UK.

Credit: Julie Ricard / Unsplash

Additionally, the wording of the Bill could create confusion around the rights of asylum seekers versus the rights of irregular immigrants.

“The Bill, and current UK policy, use asylum seekers and illegal migrants interchangeably,” said Sait. “It is true that all illegal immigrants are not asylum seekers, but asylum seekers do not have ‘safe and legal’ passageways as the policy assumes. Asylum seekers often have no other alternative than to come via risky, unconventional ways.

“In 2019, 62% of UK asylum claims were made by those entering illegally, for example by small boats, lorries or without visas. It is not clear how legislation itself or draconian measures can prevent desperate asylum seekers fleeing persecution from arriving in the UK. Moreover, these migrants include women, children, older persons and other vulnerable categories that have human rights the UK has committed to protecting.”