Are Institutions Prepared To Eradicate Gender-Based Violence?

Discussions of classing misogyny a hate crime make news headlines but can seem a pipe dream, with the Prime Minister having rejected the call. Even if it does become law, misogyny would not be wiped out overnight, so are our institutions capable of doing what it would take to end gender-based violence in UK society?

In July, the government released its strategy on tackling violence against women and girls, which included sweeping aims to increase the support available for victims and to hold perpetrators to account.

“Eradicating male violence against women can only come from systemic changes in our government, justice system, schools and workplaces, which requires collaboration and a shift in culture,” said Philpott. “It won’t come from handing out rape alarms, adding more street lighting and deploying more police out across the country, which places responsibility on the victims rather than the perpetrators and ignores women’s decreasing trust in law enforcement. We can only eradicate male violence against women and girls with increased preventative measures, not reactive ones.”

Although Sarah Everard’s murder at the hands of a police officer has sparked debate about police restructuring and retraining, the current police set-up remains the first port of call for victims of gender-based violence.

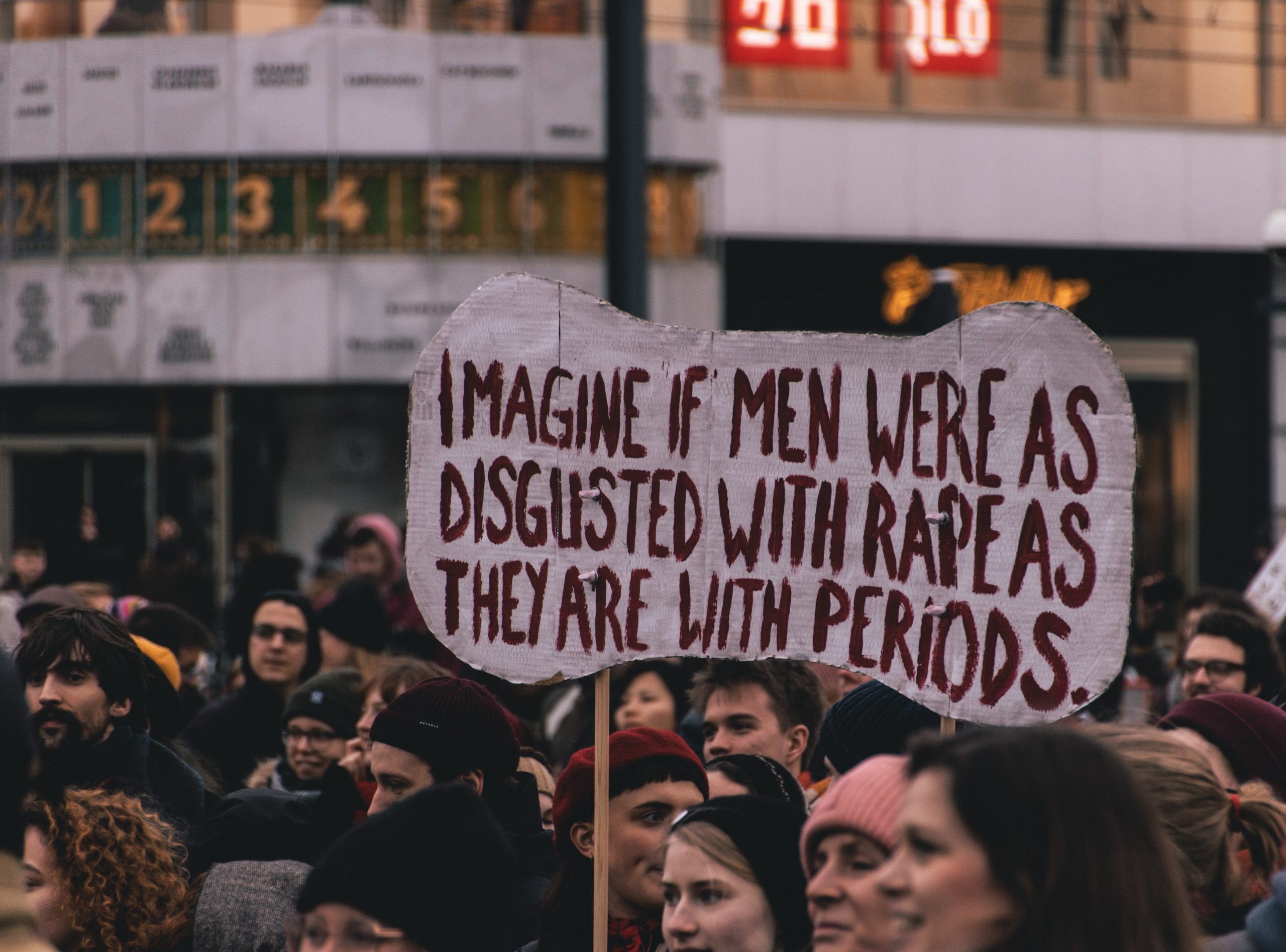

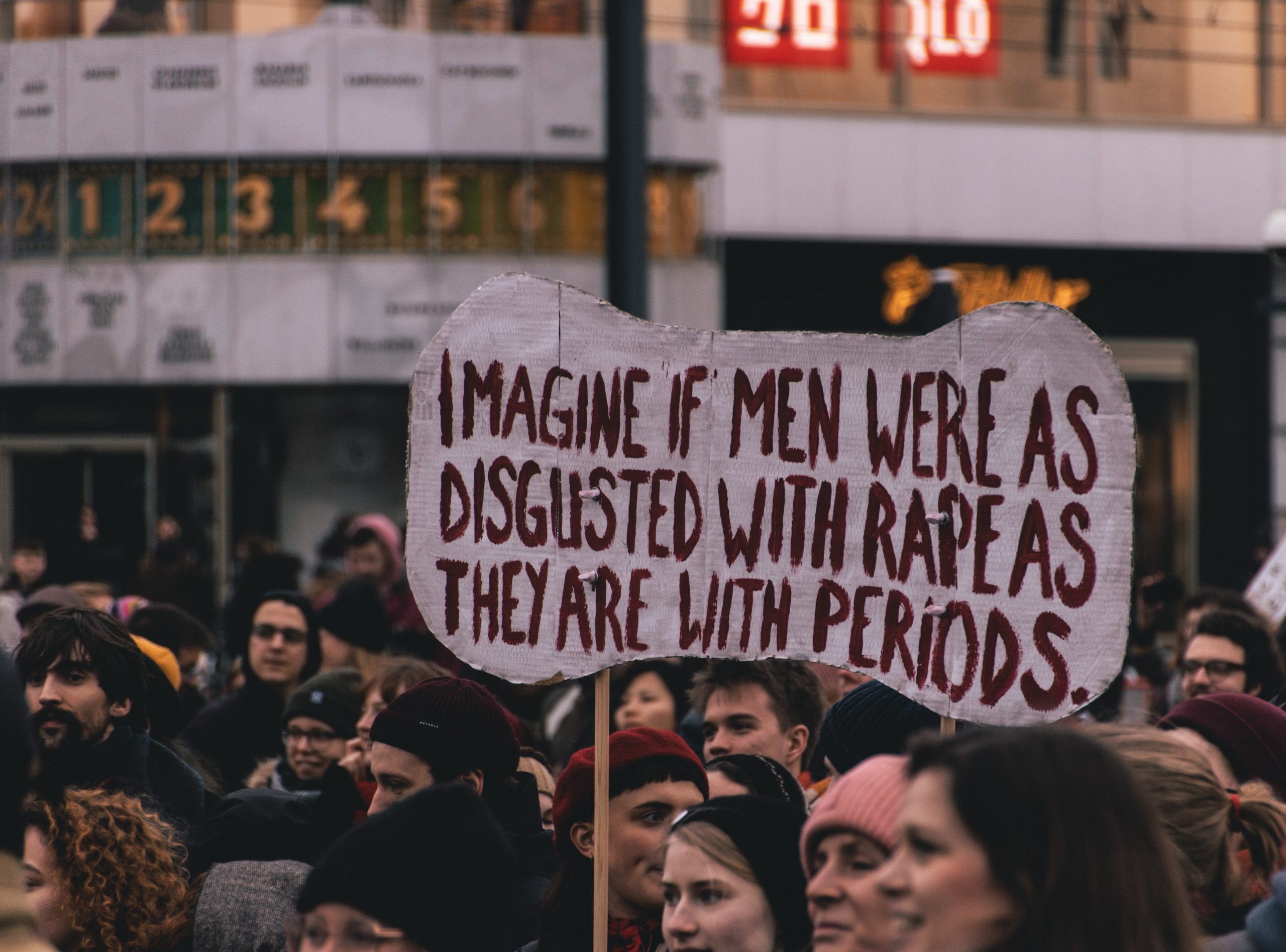

Credit: Gemma Chua Tran / Unsplash

Asahela Rose, an entrepreneur and business owner, is fighting to take her case to court after being sexually assaulted in 2019. She believes the police force needs considerable work to be able to help survivors more effectively.

“When I called the police, they sent eight male police officers to my home,” she explained. “Considering I was just assaulted by a male, it was not the best start. Then, moving forward, the next step of the investigation was very traumatic because you’re having to take your clothes off, they’re examining your body and taking pictures. The assault was traumatic enough but going through the process of the justice system has been far more traumatic than the assault itself.”

While Rose has been supported by an “amazing” Independent Sexual Violence Adviser (IVSA) who has advocated on her behalf, she says there are simply not enough advisers available to help everyone and that the police need more training to counteract biases.

“I’ve come to realise, having been in the system, because of my own experiences, that there is a difference between how I as a Black woman am being treated during my case versus how some of the girls and other women that I’ve encountered in this journey of mine,” she said. “I think more funding needs to be put into the police force, in terms of educating the police officers and how to deal with different people from different races, backgrounds, religions, because every case is unique.”

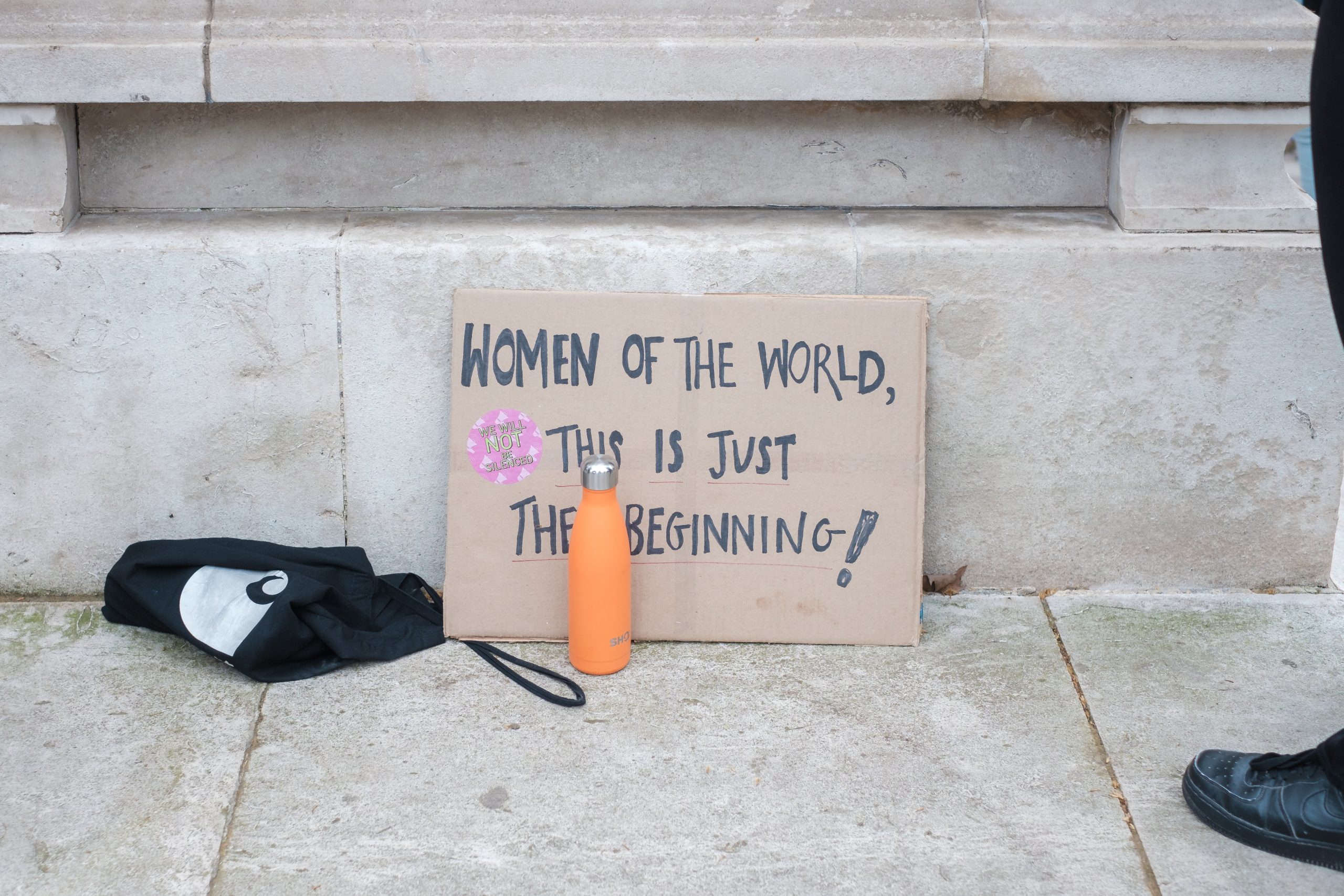

Credit: Raquel Garcia / Unsplash

Additionally, Rose hopes that the police force will stop requesting victims’ medical records – something she has refused to provide because her medical history is not relevant to the case – because it treats survivors like perpetrators with something to hide.

“Only when men, politicians, judges and the police truly exercise self-criticism, hold themselves accountable and join our struggle will we see lasting change,” said Philpott. “We need them to name misogyny, systemic gender inequality, toxic masculinity, rape, femicides, and coercive control, and we need them to understand that male violence against women and girls is at epidemic levels and happens in a context of patriarchy, fuelled by sexism and misogyny which goes unreported and unchallenged.”

Support services are also struggling to meet the needs of all those who require their services. Even though a report by Scottish Transgender Alliance indicated that 80% of trans people had experienced emotional, sexual or physical abuse and bisexual women are almost twice as likely to be abused as heterosexual women, specialist support service options for LGBTQ+ people remain minimal. The same is true for disabled women, who are twice as likely to experience domestic abuse and are almost twice as likely to experience assault and rape.