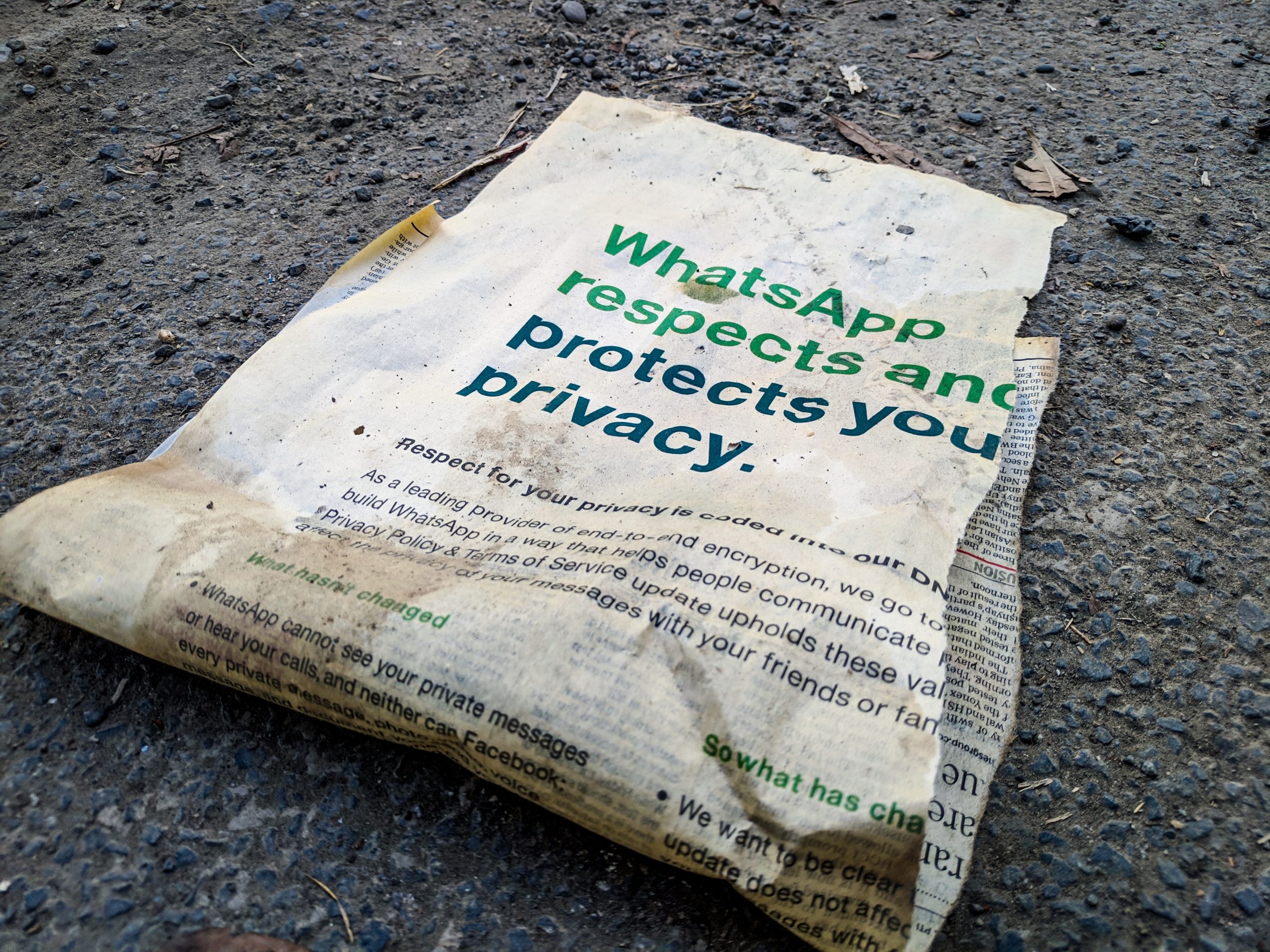

Earlier this year, it was revealed that the Home Office has hired a high-end advertising agency to create a campaign to highlight the risks that the government says end-to-end encryption poses to the public. More specifically, the campaign aims to persuade people that encryption could put at risk children’s rights.

The Home Office hired advertising agency, M&C Saatchi, paying them £524,000 to plan a campaign about the risks of encryption. The campaign, which is designed to be aimed at the public, is thought to be based on Meta’s decision to encrypt their messaging services on Facebook Messenger and Instagram by 2023.

The campaign is called ‘No Place to Hide’. Its primary objective is to prevent child sex abusers from hiding behind end-to-end encryption on social media platforms. The government’s argument is that neither social media companies nor the authorities will be able to prevent children from being harmed as a result of end-to-end encryption.

What is end-to-end encryption and what is the UK’s stance on it?

Credit: Shahadat Rahman/Unsplash

End-to-end encryption is technology designed to keep our data and conversations safe from prying eyes. The idea is that only the two (or more) people involved in the conversation specifically know what is being said, conferring privacy.

Professor Paul Bernal, a professor of IT Law at the University of East Anglia, has spoken critically of the campaign stating: “The ‘No Place to Hide’ campaign is employing ‘scaremongering’ tactics to try to convince people that end-to-end encryption is dangerous.”

This is not the first time the UK government, or any government, has used security concerns as a reason to reduce or remove end-to-end encryption and limit online privacy. One well-known example is when the FBI fought with tech company Apple to decrypt the phone used by a terrorist involved in the San Bernardino shooting in 2015. Apple declined to create the software that would have enabled the authorities to access the phone, claiming that it would set an “alarming precedent” for future cases and affect their users’ right to privacy.

The UK government in particular has taken a strong anti-encryption stance, claiming that it would diminish its capability for surveillance and curb its ability to prevent terrorism. The new campaign does not make use of this particular argument, instead focusing on child exploitation, abuse and grooming online.

“There’s a long historical record of fighting against the government fighting against encryption. What they want is for the government to be able to have access to anything,” Bernal told EachOther.

“But it misses this kind of fundamental logical problem: that is, if you create a backdoor for one group, then somebody else can exploit that backdoor. So it is absolutely inevitable that, if you are compromising encryption, then the ‘bad guys’ will get to take advantage of that as well as the ‘good guys’,” he explains.

He added: “The logic is fairly clear: create a backdoor and you don’t know who’s coming through it.”

What is the ‘No Place to Hide’ campaign?

Credit: Petter Lagson/Unsplash

The plans for this new campaign include using TV advertisements, social media, calls to action from charities focused on children and law enforcement, as well as developing in-person visual stunts that will make people think about encryption in a different way.

Rolling Stone reported that the campaign “will publish a press notice announcing that the UK’s biggest children’s charity and stakeholders have come together to urge social media companies to put children’s safety first,” and will be discussed on programmes such as Loose Women and This Morning.

M&C Saatchi also said: “[W]e are exploring a number of activations which would prompt action from both the coalition and the public… There is scope for this to involve a social media activation where we ask parents to write to Mark [Zuckerberg] via their Facebook status.”

They also considered installing a glass box in a public space with a child and adult actor inside, where throughout the day, the glass will become opaque and therefore prevent people from seeing what is going on inside, Rolling Stone reported. This is meant to be an analogy for encryption, getting the public to see it the same way and therefore “force Facebook to evaluate their sense of responsibility” towards children.

Would banning end-to-end encryption really make children safer?

Credit: Kelly Sikkema/Unsplash

While there is definitely an issue of exploitation and abuse on the internet, as well as security concerns, Prof Bernal questioned whether the government is exaggerating the extent of the issue in its campaign.

“The government tends to overestimate how much having these ‘backdoors’ would actually help. And they don’t ever provide empirical evidence to prove it,” he says. Prof Bernal believes that removing or denying end-to-end encryption will in fact make everyone, including children, less safe.

“You’re giving an opening for exactly the people they’re trying to protect them against. There’s a lot of history here, where there are children-only places on the internet and they often become targets for predators, paedophiles and so on,” Prof Bernal said.

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), which is the UK’s data watchdog and oversees the protection of people’s data, has similar opinions. A few days after the launch of the campaign, the ICO intervened in the debate and warned that delaying the introduction of end-to-end encryption puts “everyone at risk”.

Stephen Bonner, the ICO’s executive director for innovation and technology, said: “End-to-end encryption serves an important role both in safeguarding our privacy and online safety. It strengthens children’s online safety by not allowing criminals and abusers to send them harmful content or access their pictures or location.”

Professor Bernal also noted that the authorities have other surveillance methods of protecting the public from criminality that do not require the removal of end-to-end encryption. Additionally, there will always be a way to get around the surveillance techniques employed by the authorities or by tech companies. Instead, Bernal suggested, we should be teaching adults and children, “good habits for communication and making sure they’re aware of what the real dangers are”.

Credit: Compare Fibre/Unsplash

“It’s about good parenting and good schooling, and a secure environment, which children can use themselves. They shouldn’t be wrapped in cotton wool: they should be given the tools they need to survive.”

Bonner also said that accessing encrypted content was not the only way to protect children, as other methods previously used by law enforcement, such as infiltrating abuse rings, listening to reports from children targeted by abusers and using evidence from convicted abusers, can continue to work.

He added: “Until we look properly at the consequences, it is hard to see any case for reconsidering the use of end-to-end encryption – delaying its use leaves everyone at risk, including children.”

“You can never make everything completely safe. We may find it very difficult to accept that that’s the case, but it’s not possible to guard against everything,” Professor Bernal added.

Of course, “bad guys” will use encryption if it’s available, just like we would, he says. People who are in favour of encryption “don’t and shouldn’t shy away from the fact that the tools we use can also be used by bad people”.

“But that’s true of every tool that we have,” Prof Bernal argued. “It’s true of weapons, just as it’s true of communications tools. It’s also true of transport methods – for example, during the 7/7 London bombings, we know the culprits travelled by bus and by train: does that mean we should ban buses and trains, just because bad people can travel on them? No, we shouldn’t.”

What are the benefits of end-to-end encryption?

Credit: Christian Wiediger/Unsplash

“What’s depressing is how unwilling ministers are to have an informed, intelligent, balanced debate about it, instead relying on emotional and often distinctly fact-limited campaigns like this one,” Bernal said.

The advantage to end-to-end encryption, according to Bernal, is that it is necessary for people to function both online and offline.

“Communications online underpin every bit of our activity in the real world,” he says. “If you’re going to ban encryption, that can compromise people’s real life ability to, for example, meet up together to exercise their human rights of association and assembly”.

“You will also compromise their ability to communicate privately and securely, and that’s what banning encryption, or even reducing the capability of online encryption, would do.”

Prof Bernal added that often campaigns such as this one, as well as previous discussions about online anonymity and encryption, attempt to find a middle ground. The problem is, there is no effective compromise.

“There are some things which you don’t compromise on. There isn’t a middle ground between encrypted and non-encrypted,” he says. He jokes that it is parallel to being pregnant: “You’re either pregnant or not pregnant. There is no in-between.”

Encryption will also ensure that we are being kept safe from scrutiny from authorities that have no right to impose on our privacy.

How does legislating against encryption affect our rights?

Credit: Tushar Mahajan/Unsplash

In previous privacy versus safety arguments, experts have noted that removing or withholding end-to-end encryption would affect our rights to privacy, as enshrined in the Human Rights Act (1998). It would also affect rights to freedom from discrimination and freedom of expression – both of which are helped by the access to the internet and encrypted online spaces.

Prof Bernal agreed: “It reduces our right to privacy because it means it’s harder for us to communicate. But, it’s not just privacy.”

“We’re talking about the right to privacy online, which underpins a whole raft of other rights, including association, assembly, freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial, freedom from discrimination and so on. Because when you remove privacy, you give other people a chance to undermine those other rights. It’s an underpinning right, as well as a right in itself.”

Prof Bernal mentioned oppressive regimes in various parts of the world, highlighting the example of former East Germany and Hong Kong, where the loss of anonymity, online privacy and encryption encourages conformity, as dissidence online and offline would put those citizens at risk. He says: “If you know you’re going to be watched, your actions are compromised.”

In Hong Kong in particular, the National Security Law prevents its citizens from speaking out against the Chinese government on social media or they can be tried for treason. The government can analyse this information through China’s mass-surveillance programmes, forcing pro-independence activists deeper into the internet to try to find anonymity, privacy and encrypted platforms so that they will not risk their safety or have to serve jail time as a result.

Credit: Maxim Hopman/Unsplash

Without end-to-end encryption, if the UK government were to shift to a more oppressive regime, it could mean that anyone who opposes them and what they do could be at risk for writing an article, a tweet or even a disparaging message to a friend.

The Police, Crime, and Sentencing Bill has already granted more powers to the authorities in clamping down on protests and giving them wider stop and search powers. It is not an unimaginable leap from that to monitoring citizens’ online communications.

Therefore, without the underlying right to privacy, there is a potential domino effect towards other rights.

Professor Bernal added: “They want to have some kind of magical backdoor that only the ‘good guys’ can get into. But, who are the ‘good guys’?”

“In this case, the ‘good guys’ are security and intelligence services and the police and other law enforcement agencies. Now, they may be good guys in some circumstances, but they’re not always good guys”.

“We know all too well from the recent past how the police has what they would like to call ‘rogue elements’, but the police have bad people in them who do bad things. The same is obviously true of any service,” he said.

What does the Home Office say about ‘No Place to Hide’?

Credit: Lianhao Qu/Unsplash

A Home Office spokesperson told Rolling Stone in a statement: “We have engaged M&C Saatchi to bring together the many organisations who share our concerns about the impact end-to-end encryption would have on our ability to keep children safe.”

The ‘No Place to Hide’ campaign website states that the steering group behind the campaign wants to “work together to ensure we keep children safe online without compromising user privacy.”

It notes that the group is “not opposed to end-to-encryption in principle and fully support the importance of strong user privacy. Instead, our campaign is calling for social media companies to work with us to find a solution that protects privacy without putting children at even greater risk”.

It argues that an estimated 14 million reports of child sexual abuse online could be lost each year due to end-to-end encryption, attributing the information to the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children.

The statement adds: “We want social media companies to confirm they will not implement end-to-end encryption until they have the technology in place to ensure children will not be put at greater risk as a result. They need to show that the changes will not make it easier for child sex abusers to groom children, make, share or view sexual images of children, and avoid detection by law enforcement agencies”.

Credit: Szabo Viktor/Unsplash

“We are not opposed to end-to-end encryption, as long as it is implemented in a way that does not put children at risk. We are in favour of both strong privacy and children’s safety and urge social media companies to protect both.”

Damian Hinds, Home Office minister, called for a “more balanced debate” on the issue of encryption. He wrote in The Times: “There is a risk that end-to-end encryption, without the right safety capabilities, blinds companies and law enforcement, taking us backwards. Neither this government, nor society as a whole, could accept that.”

Similarly, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), one of the steering group members for the ‘No Place to Hide’ campaign, responded to the Information Commissioner’s advocacy for encryption by saying that poor implementation of encryption could put children at risk.

Children’s charities want it risk-assessed

Andy Burrows, head of NSPCC’s child safety online policy, said: “That’s why the NSPCC wants companies to risk-assess end-to-end encryption and balance the privacy and safety requirements of all users, including young people, to ensure it is rolled out in the best interests of the child.”

The Home Office told EachOther its number one priority was public safety. A Home Office spokesperson said:

“Our number one priority is the protection of children and public safety. Technology companies must take responsibility for tackling the most serious illegal content on their platforms and protecting their users, including our children.”

“The UK Government supports encryption and believes that end-to-end encryption can be implemented responsibly in a way which is consistent with public safety. Our view is that online privacy and cyber security must be protected, but that these are compatible with safety measures, that can ensure the detection of child sexual exploitation and abuse”.

The Home Office added, “We have engaged M&C Saatchi to bring together the many organisations who share our concerns about the impact end-to-end encryption would have on our ability to keep children safe”.

“M&C Saatchi’s support to partners includes PR and communications advice to work towards the shared goal of protecting children online.”

The department said that it has launched a new tech fund to develop technologies that will detect content containing child pornography in end-to-end encrypted software. The Home Office told EachOther:

“Last year, we also launched a £550,000 Safety Tech Challenge Fund, which is focused on developing innovative technologies to detect child sexual abuse content in end-to-end encrypted environments, without compromising user privacy”.