Article 10 and Article 11 of the Human Rights Act (HRA) state that everyone has the right to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly. However, this does not always hold true for marginalised groups.

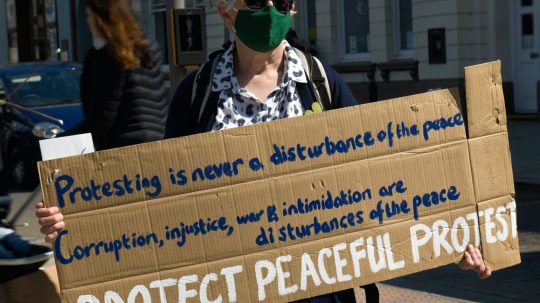

It’s a Saturday afternoon in April, and alongside thousands of others I peacefully walk the streets of London at the ‘Kill the Bill’ Demo, protesting against the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, two people in hi-vis bibs standing at the side of the march are arrested by the police. These are legal observers from the Black Protest Legal Support – an agency led by ethnic minority lawyers who provide free legal advice to protesters.

Sam Grant, the head of policy and campaigns at Liberty, called the arrest of the two legal observers “an intimidation tactic to deter protest”.

Both observers were released without charge, and more than 100 other arrests were made at the protest. The heavy-handed tactics of the police are not uncommon and are often targeted at marginalised groups.

The right to freedom of assembly and association (Article 11 of the HRA) in the UK is clear. Under Article 11, everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

According to Liberty: “The State can’t interfere with your right to protest just because it disagrees with protesters’ views, because it’s likely to be inconvenient and cause a nuisance or because there might be tension and heated exchange between opposing groups. Instead it must take reasonable steps to enable you to protest and to protect participants in peaceful demonstrations from disruption by others.”

Protestors felt the media was silencing us

Alongside police hostility towards some protests comes the role the media play in reporting events. The power of reporting should not be underestimated – it has the ability to sway public opinion and raise awareness of particular causes and issues.

But when it comes to the media reporting on campaigns organised by or dedicated to marginalised groups, coverage can be sparse or not wholly supportive.

Only last week was Sky News forced to apologise for mistakenly reporting that a protest march was a gathering of crowds marking the Queen’s death. The demonstration was in fact for Chris Kaba, an unarmed 24-year-old man who was shot dead by a Metropolitan police firearms officer.

Despite several Justice for Chris Kaba protests being organised around the country; some media outlets have remained relatively quiet on reporting the story. A group of protesters at the march in London told me they believed that “the media wanted to silence the protest, despite it deserving coverage.”

Alarmingly, this is not an isolated case. Protests last summer criticising the UK government’s handling of the Afghanistan crisis were only briefly reported on by predominantly London-based outlets. This is despite the fact thousands attended the protests demanding the government do more in protecting Afghan citizens from Taliban rule.

Stark contrasts can be seen between the reporting of that protest and the recent Ukrainian solidarity marches in London. Not only did media outlets report the story for a significantly longer period of time, but key figures, including the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, praised the marches. He said Londoners stand “shoulder to shoulder with Ukraine in its darkest hour”. While the majority of media outlets reported on Ukrainian solidarity, it brought up concerns that the media reports on refugees from Europe and the global south differently.

The fake free speech crisis

Right-wing media would like us to believe we are experiencing a free speech crisis – there’s a generation of ‘snowflakes’, students are no-platforming speakers and marginalised groups are tearing down historical statues.

This harmful rhetoric seeks to undermine legitimate campaigns, and marginalised groups are being targeted. It is not just freedom of assembly that is under attack by this fake crisis, it’s freedom of expression too.

A report by Amnesty in 2017 analysed tweets received by 177 female MPs in the UK. Findings showed that 41% of the total number of abusive tweets were directed towards the 20 female ethnic minority MPs. Asian and Black female MPs also received 35% more abusive tweets compared to their white colleagues.

The anonymous abuse directed towards marginalised communities and leaders is an attempt to stop freedom of expression through scare tactics.

The report was conducted by human rights researcher Azmina Dhrodia, who concluded: “Whether women use social media platforms as public figures or for personal use, the threat of abuse is all too real, and it is having a silencing effect on women’s participation online and in the public sphere.”

Knowing your rights

Despite attempts to curtail the freedom of speech of marginalised groups, it is imperative we continue to exercise our rights of expression and assembly.

This is where education can help solve the problem. Understanding our rights in situations such as being questioned at a protest or threatened on a social media platform can help us feel more protected and confident.

Legal education in schools is currently lacking; a report by the House of Lords in 2018 stated that young people’s legal knowledge is in “a parlous state”. The government must improve the curriculum to incorporate the teaching of law from a young age.

Right now, external organisations such as the Bingham Centre are helping spread awareness of what our rights are.

The explainer video above is a useful tool to understanding freedom of speech and how we all, regardless of who we are, deserve the same level of protection of our rights and no one has the power to take that away.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.