The Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) is the landmark legislation that prevents people in the UK having their rights trampled by the state. It was introduced in part to ‘bring rights home’. Almost 25 years later, the government proposes to overhaul it and replace it with a new Bill of Rights in a move that has been described as a ‘power grab’ and a ‘con’.

In his speech for the state opening of parliament, Prince Charles stated that in the next year the government would introduce a Bill of Rights to ‘ensure the constitution is defended… [and] restore the balance of power between the legislature and the courts’. The announcement came after the government had formally consulted the public, advocacy groups and human rights experts on its plans to reform the Human Rights Act.

Controversy has been mounting

The concept of a Bill of Rights has been banded around some circles in Westminster for years, but the prospect of it actually becoming a reality has been more apparent since the government last year launched a controversial and heavily criticised consultation on the functioning of the current HRA.

Many civil liberties groups, barristers and human rights activists have condemned the idea of a new Bill of Rights from the start, but members of the House of Commons have also now been critical of Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab’s new Bill of Rights Bill (BORB). After the Speaker of the House, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, expressed his frustration at the bill’s contents being briefed by the government to the media before they had been shared in parliament, MPs, Peers and over 150 organisations called for them to be subjected to pre-legislative scrutiny – a call the government rejected.

There will be less onus on public authorities proactively to safeguard our rights

One of the main effects of parliament potentially passing the Bill of Rights would be to dilute positive obligations (BORB clause 5). Positive obligations place a duty on public authorities proactively to safeguard people’s rights. The Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) explained in response to the consultation on the HRA why the case for bringing any such changes is unconvincing:

“The reasons offered for reviewing the case law on positive obligations are weak. The consultation refers to the need for parliamentary oversight, but, of course, Parliament has the possibility to legislate if it judges that the case law needs correction. The consultation also refers to the legal uncertainty allegedly created, but it is the role of the courts to gradually clarify the law and, from the evidence, that is what they have been doing.”

1/4 Among many others, the Bill of Rights proposals on positive obligations are worrying. As this @CAJNi response to the consultation shows, ECHR positive obligations have assisted victims of crime, sexual abuse, human trafficking and child neglect. https://t.co/QwjqMc7kP4 pic.twitter.com/OB8h0FCXeN

— Rory O'Connell (@rjjoconnell) June 27, 2022

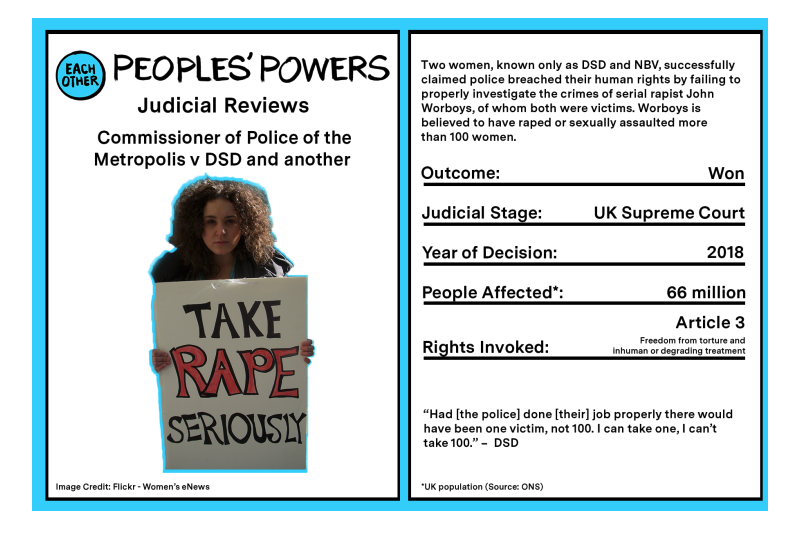

These positive obligations, now at risk, are a vital protection for everyone living in the UK. In the past, they have led, for example, to victims of police violence receiving justice under Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) – the right to freedom from torture, inhuman and degrading treatment. They have also led to investigations into human trafficking – an illegal practice that breaches Article 4 of ECHR which prohibits slavery and forced labour.

This is not a drill.

The Government wants to rip up our Human Rights Act with the #RightsRemovalBill.

Share the video. Sign the petition. Speak up to #SaveYourRights pic.twitter.com/AVNww6fmBn

— Liberty (@libertyhq) June 24, 2022

Making justice less accessible and deflecting scrutiny from the government

Clause 15 of the Bill of Rights proposes a ‘permissions stage’ which would act like a filter to throw out certain cases before they even got started. The Bill states that no one is to be allowed to bring proceedings against a public authority unless they have sought and been granted permission from the court that the proceedings should be held. Under the proposed legislation, if that person is rejected by the intended court, they are allowed to appeal to the court but they are prevented from appealing to any other court.

The Bill has come under scrutiny from leading human rights barristers, who have dubbed it a ‘con’ which sets out to limit scrutiny by the courts and prevent individuals holding the government and statutory authorities to account.

My letter in todays @thetimes pic.twitter.com/bTZ7XXoU0a

— Adam Wagner (@AdamWagner1) June 24, 2022

Another way in which the Bill will affect people trying to access justice is by introducing a threshold test which will mean additional cost. The proposal comes against a backdrop of years of cuts to legal aid, which has left many unable to access justice.

Shadow Justice Minister, Ellie Reeves, called out the government in the House of Commons by stating the Bill of Rights is an attack on women. Reeves stated: “This Bill of Rights ‘con’ isn’t just an attack on on victims of crime who the state has failed to protect. It’s an attack on women. Women have used the Human Rights Act to challenge the police when the police have either failed or refused to investigate rape and sexual assault cases.”

This Conservative Government’s Bill of Rights con is an attack on women.

It will make it harder for victims of rape to get justice.

But it comes as no surprise from a Govt that has effectively decriminalised rape. pic.twitter.com/hLg1coGyi0

— Ellie Reeves (@elliereeves) June 22, 2022

Hannah Couchman, Senior Legal Officer at Rights of Women, speaking to BBC Woman’s Hour, said at her charity they were especially concerned “because of one particularly egregious part of this bill that says there will be an end to what we call positive obligations… Two victims of the Worboys case were able to use the human rights act to challenge those failures [by the police] and to ensure the police were held accountable and re-emphasised that their human rights meant that there was an obligation for the police to effectively investigate what they had completely failed to do.”

One of our People’s Powers cards to highlight the importance of Judicial Review

The government wants to make deportations easier

The Bill, if passed, would make it easier for the government to deport people from overseas who had served their time for a crime in the UK. In order to invoke their right to family life (Article 8 of the HRA), the individual’s loved ones, in the future, would have to prove that a family member would come to extreme, exceptional, overwhelming and irreversible harm if they were removed from the country.

In fact, 25 seconds into Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab’s video introducing the Bill, he states that one of its primary intentions is deliberately to make such deportations, which separate families, easier:

Our modern Bill of Rights will strengthen the UK tradition of freedom of speech, and better protect the public from dangerous criminals.

We are restoring a health dose of common sense into the justice system. ⤵ pic.twitter.com/ppzQF5I9fe

— Dominic Raab (@DominicRaab) June 22, 2022

Currently, a foreign national serving a sentence of 12 months or longer is eligible for deportation, including those found guilty by association under the doctrine of joint enterprise. The eligibility criteria for deportation therefore include individuals who have not committed any violent crime. Such deportees are sometimes sent to countries with which they are now unfamiliar and where they do not speak the language.

The government claims the Bill of Rights will protect free speech

Organisations that have made it their mission to protect free speech have called the current government out for introducing a number of other Bills that actively limit free speech. Concerns have been raised that the national security bill, the online safety bill, the higher education (freedom of speech) bill, the public order bill, and the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act all threaten free speech in the UK, which is currently protected under Article 10 of the HRA. Given this track record, when the Deputy Prime Minister claims that the Bill of Rights will strengthen the UK tradition of freedom of speech, some journalists and rights campaigners have responded with scepticism. Anticipating accurately a lack of new substance on the subject of free speech in the Bill, Natasha Hirst, Vice-President of the National Union of Journalists, and Chris Frost, emeritus Professor of Journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, wrote:

“Suggesting that wokery, political correctness or cancel culture are good reasons to be concerned only suggests that you don’t understand what freedom of expression means. Raab does not explain how freedom of expression will become a trump card.”

The Ministry of Justice has stated: “The Bill will ensure courts cannot interpret laws in ways that were never intended by Parliament and will empower people to express their views freely.”

The Bill of Rights Bill stands to dilute state accountability in many areas of UK life. As such, it is the latest in a slew of legislation which, especially when taken together, fundamentally weakens the hard-won human rights which exist to protect us all.

Visit EachOther’s spotlight on the Human Rights Act to see just how much is now at stake.