This is an interview, first published in Rocks Festivals Blog, with Sarah Wishart, EachOther’s Creative Director and the producer and director of our first feature-length documentary, ‘Excluded’.

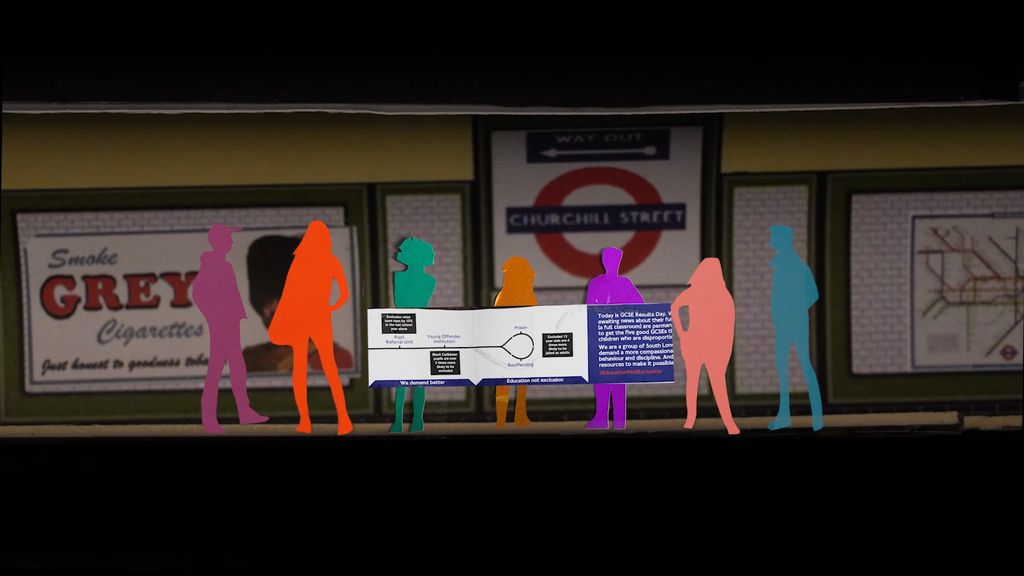

One of the wonderful things about our modern times is that more and more voices are being heard on issues that desperately need to be addressed. Whilst there is a long way to go, in 2018 a group of determined South London students started a movement for #EducationNotExclusion by using the London Underground to make a powerful and subversive statement about exclusions on GCSE results day.

A Tube map from ‘school to prison’ could be seen on Northern Line trains, shining a spotlight on the number of pupils permanently excluded from school each day. The satirical poster shows a direct line from ‘sent out of class’, stopping at ‘permanent exclusion’ and with ‘prison’ as its final destination. People were forced to take notice and address a huge problem in the education system over the whole of the United Kingdom. Dr Sarah Wishart, the creative director of a UK-focused charity EachOther, directed the impressive and important documentary ‘Excluded’, shown at Hastings International Film Festival, and captures voices we need to hear as well as setting up a collaborative and informed environment where the young people featured on the film were all involved in the creative decision-making and are listed as co-creators.

A clever, admirably collaborative and thought-provoking first feature documentary where we are not focusing on politicians or journalists, but giving young people the floor so that the audience hears from those directly affected.

Credit: ‘Excluded’/EachOther

What is your background and what brought you to documentary making?

I have a background in performance art with a PhD on collaborative artwork and the processes of how they get made. I work with film, sound and text in my practice and so this job is a weird melding of all my skills and knowledge. EachOther is a human rights space for digital journalism so I find myself involved in all sorts of formats. We historically have made short explainer films about rights issues. This was our first feature length documentary and it was amazing to do.

Where did the initial idea for the film come from?

Originally I’d been looking to expand onwards from my film project funded by the EHRC with young children talking about human rights. We visited four Rights Respecting Schools around the country in the process of creating ‘Fair Play’. However, the minute I heard about the ad hack about school exclusion that took place on the Northern Line in the summer of 2018, everything changed. I originally thought the format of the film would be the journey into finding those young people and their story, but I actually made contact with them very quickly which totally shifted the whole project. My desire to look at education with young people around rights grew into a film project that listened to what these young people wanted to talk about in relation to rights, and that was exclusion.

How did you go about developing the idea after reading about the hack?

I tend to find that the restrictions on a project are what develops the project. Who can be involved, how do we pay them, how do we film etc. and restrictions on this project were fairly significant! It was initially a passion project that I hoped we could get some funding for but until we found any money, I was eeking out shoots around other work we had on. Just as we found out about a small amount of funding, the pandemic hit. We were just booking filming time in Scotland and we had to completely rethink what we were going to do. I sat with the idea that perhaps we had to give it up, but I was working with a fabulous producer who told me about how her partner was sending microphones out to guests on his show – and we followed suit. We bought microphones and sent them out to all the young people, and started all our workshops on zoom.

Credit: Kadeem/’Excluded’

How did you find the young people who you ended up working with?

We worked with partner organisations, as we aren’t a client-facing charity, so we have to build relationships with other charities and individuals working in relevant spaces. Some of the young people were then introduced to the project through their friends who were already involved. Two young people I met when I was presenting our work at a young people driven event in Leytonstone.

It always takes time to find people who want to get involved with a project like this, and time for the organisations we engage with to build our project into their own timelines. People have to feel like they understand what we and all our team are going to do and how we’re going to work with the young people. Time is a huge issue.

Credit: Joe/’Excluded’

How did you direct from afar?

We’d had workshops with all the young people and circulated questions and ideas back and forth. We also worked with some of the young people’s youth workers and on occasion, these guys helped with the interviewing.

What were the advantages/pitfalls of working this way?

It was an amazing feeling to work in this way – to stand back and enable other people to be involved in a way they weren’t expecting. In relation to the pitfalls, time is always a massive issue. There are inevitable delays when you’re working with such a varied and far flung cohort. Some people needed more support so that took time to enable.

Credit: Betty/’Excluded’

What did the students bring to the table in terms of the actual film making?

We started with an initial brainstorming session to establish trust, discover what participants anticipate the film could achieve along with listening to what they want it to achieve and enable the space for discussion about how they want to be involved. We also saw this as a useful opportunity for discussions about consent and to get input around creative themes which could run through the project. We focussed primarily on listening to the attendees with only a few open questions to guide the workshops and give them a loose structure. We circulated in the session a rough cut of the footage we had already shot to give them a sense of what the project looked like and to anchor the discussion. After they’d watched it in the session, we dedicated a good proportion of the session to getting feedback on the film. We then opened a discussion centered around those questions.

From the workshops we identified that the young people wanted us to include spoken word, photographs of some of the young people throughout their education, and a letter from one of Natalia’s uncles who had ended up in prison after his exclusion. The group felt like we needed to include more detailed stories of exclusion and so we asked for nominations of people whose story they thought should feature. A number of names were put forward from within the group and they also requested that youth MPs of some description were included.

Although we approached several young Mayors in London, we found greatest engagement and interest when we approached the Scottish Youth Parliament. We discussed sending out audio recording equipment which is how we captured several of the voices throughout the next year. The young people felt there should be a narration track and that a young person should do that “in terms of the voice-over it is quite important that it should be a young person that does it, to really be able to capture the story, it is ok to drill home the points that are most important.” We implemented all of these aspects so the workshops and the co-production they allowed were therefore absolutely central to the development of the film.

Credit: Jordane/’Excluded’

How did you use stop motion techniques to give anonymity?

This was done in-house by my film producer Jack Satchell, we decided we wanted to try and summarise the actions of the ad-hack whilst keeping everything anonymous. I absolutely love stop motion and have always wanted to work on an animation project with stop motion animators and Jack, who’d never really worked with this kind of format before, jumped at the chance to illustrate it. It was great finding a tube train model!

‘Excluded’ came Runner-Up in the Best Documentary category at the Hastings Rocks Film Festival this month.