Black human rights activism has a long history in the UK. In honour of Black History Month 2020, EachOther explores the achievements of ten Black British human rights trailblazers.

Black history in the UK is British history. From Olaudah Equiano to Diane Abbott, Black Britons have a long history of campaigning for basic human rights and equality. Every October, a month is dedicated to acknowledging the rich and inspiring history of Black Britons. In honour of Black History Month 2020, here are ten of the UK’s most inspiring Brits.

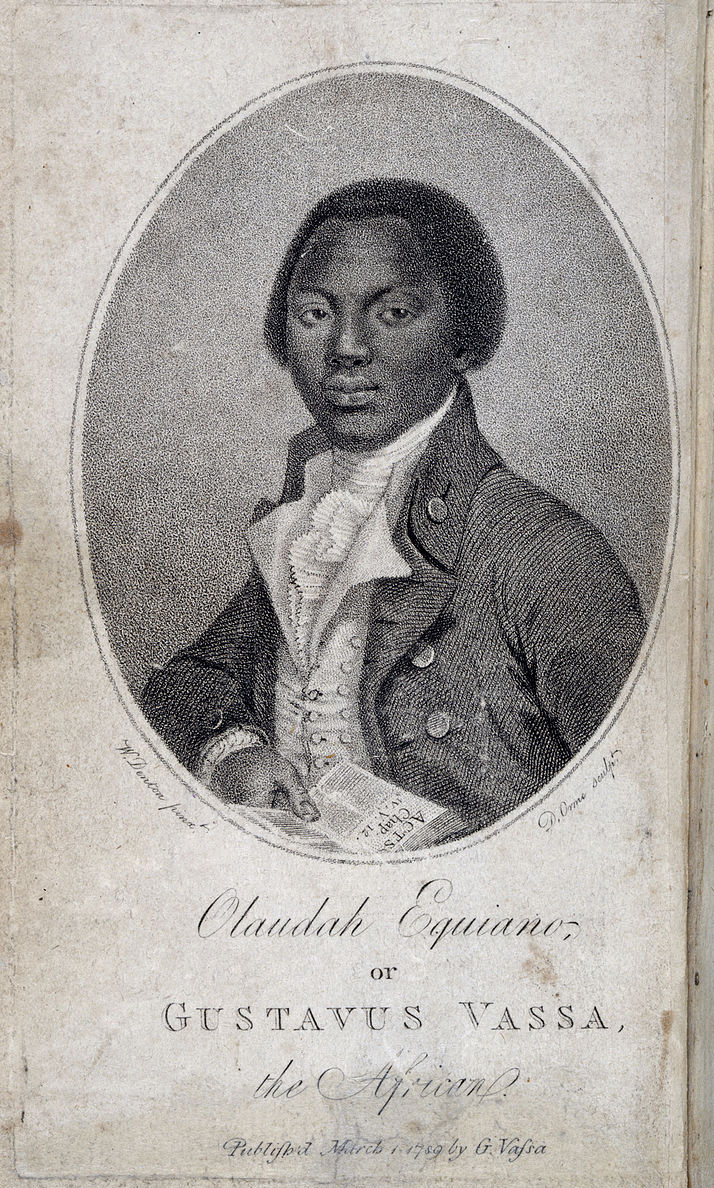

Olaudah Equiano (1745 – 31 March 1797)

Olaudah Equiano was a writer and abolitionist. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Olaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa, was a writer and abolitionist.

In his autobiography, he states that he is from the Eboe region of the Kingdom of Benin. He was enslaved as a child and taken to the Caribbean.

There, he was sold to a Royal Navy officer – and then sold twice again before buying his freedom in 1766.

After securing his freedom, Equiano spent 20 years travelling across the world, including to Turkey and the Arctic.

Equiano moved to London as a freedman, and became part of the “Sons of Africa” movement – an abolitionist group of Africans living in Britain.

Equiano was also a member of the radical working-class London Corresponding Society, which aimed to extend the right to vote to working men.

In his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, he discussed the atrocities of the slave trade. It is believed that Equiano’s book helped contribute to the British Slave Trade Act 1807.

Ottobah Cugoano (1757 – after 1791)

Ottobah Cugoano was sold into slavery at the age of 13. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Ottobah Cugoano, also known as John Stuart, was an abolitionist, anti-imperalist, and natural rights philosopher.

He was captured and sold into slavery at the age of 13, and worked on a plantation in Grenada.

In 1772 he was bought by an English merchant, and accidentally freed following the ruling in the landmark Somerset Case in 1772, which sparked the beginning of the end of Britain’s slave trade, due to his owner misunderstanding the legislation.

After that, he joined the Sons of Africa, and became a leader of the Black British community.

In 1786, he played a pivotal role in saving Henry Demane – a Black man who was kidnapped and due to be shipped to the West Indies as a slave.

In 1787, assisted by Olaudah Equiano, he published Thoughts and Sentiments on the Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787).

The narrative was sent to King George III, the Prince of Wales. However, much of the royal family remained opposed to the abolition of slavery.

In 1791, Cugoano published a shorter version, Sons of Africa, where he expressed support for the creation of a colony in Sierra Leone by the British for London’s Poor Blacks – mainly compromising of freed African-American slaves.

In 1783, he caused controversy by suggesting William Wilberforce was a hypocrite because he refused to support abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

Cugoano also called for the establishment of schools for African students in Britain.

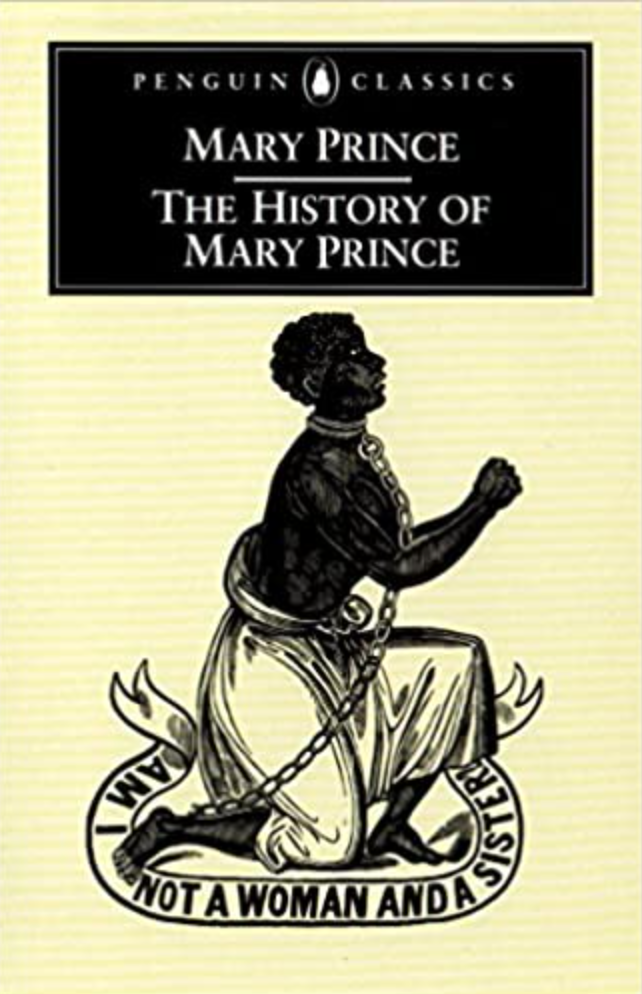

Mary Prince (1 October 1788 – after 1833)

Mary Prince’s life was the first account of a Black woman published in Great Britain. Credit: YouTube/screenshot

Mary Prince was an abolitionist and autobiographer.

She was born into slavery in Bermuda in 1788 and was sold, alongside her mother.

Mary was sold again in 1806, in 1810, and lastly in 1815 to Adams Wood.

She married Daniel James, a freedman and carpenter, in 1826 while she was still enslaved.

In 1828 the Wood family travelled to England taking Prince with them.

Prince did not have the financial means to be self-sufficient and, unless the Wood family officially freed her, she would not be able to return to Antigua to her husband without being re-enslaved upon arrival.

While Wood wrote a letter allowing her to leave his control, he did not formally free her – and suggested in his letter that no one should hire her.

Prince took shelter with the Moravian church in Hatton Garden, and started working for abolitionist Thomas Pringle, who offered assistance to Black people.

The Woods left England in 1829 but refused to free Prince or allow her to be purchased out of his control, meaning she would be unable to return to Antigua without being re-enslaved.

Pringle hired Prince to work at his own household, and encouraged her to arrange for her life to be transcribed by Susanna Strickland, which became The History of Mary Prince; it was the first account of a Black woman’s life published in Great Britain.

In her autobiography, she writes: “Mothers could only weep and mourn over their children, they could not save them from cruel masters – from the whip, the rope, and the cow-skin.”

William Cuffay (1788 – July 1870)

William Cuffay campaigned for better working hours. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Willam Cuffay was a chartist.

He was born in Kent, England, in 1788 to an English woman and a freedman from Saint Kitts.

He worked as a tailor, and was a campaigner for better working hours. He called for 10-hour work days between April-July, and 8-hour work days for the rest of the year – with a pay of 6 shillings and 5 pence per day.

Cuffay was sacked and blacklisted as a result, and in 1839 helped form the Metropolitan Tailors’ Charter Association.

In 1841, he was elected to the Chartist Metropolitan Delegate Council. In 1842, he was elected to the national executive of the National Charter Association, and became president of the London Chartists later that same year.

Cuffay was also one of the organisers of the Chartist rally on Kennington Common in April 1848.

Cuffay was arrested as a result, and accused of “conspiring to levy war” against Queen Victoria; he was sentenced to 21 years penal transportation in Tasmania.

He was acquitted three years after, but spent the rest of his life in Australia, where he again became involved in trade union and political issues.

Before his death in 1870, he played a key role in amending the Mater and Servant Law in the colony.

Harold Moody (8 October 1882 – 24 April 1947)

Harold Moody plaque, Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Harold Moody was a physician and civil rights activist.

He was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1882 where he spent his youth.

He sailed to the UK in 1904 to study medicine at King’s College London, finishing top of his class in 1910.

After medical school, Moody decided to open his own medical practice in 1913 after it became apparent he would be refused work due to the racism in British society at the time.

In 1931, Moody formed, and was president of, the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) – an organisation with a goal of strengthening the rights of Black people in Britain.

The LCP had various aims including the commitment to protect the socio-economic interests of people of colour, the welfare of people of colour, and coordinate with organisations sympathetic to people of colour.

In 1944, the LCP organised a three day conference in London, where they drew up the “Charter of Coloured People”, which demanded equality for people of colour in the UK.

He also campaigned against racial prejudice in the armed forces, and is credited with overturning the Special Restriction Order (or Coloured Seaman’s Act) 1925.

A discriminatory measure in the Act sought to provide subsidies to merchant shipping employing only British nationals, requiring seamen born overseas – many who had served Britain in World War One – to register with the police.

Dame Jocelyn Barrow DBE (15 April 1929 – 9 April 2020)

Dame Jocelyn Barrow was a politician and community activist. Credit: University of Law, YouTube

Dame Jocelyn Barrow was an educator, community activist, and politician.

She was born in Trinidad in 1929, and was an active member of the People’s National Movement there.

She arrived to the UK in 1959 to read English at the University of London.

She was a founding member, general secretary, and later vice-chair of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination – an organisation which lobbied for race relations legislation between 1964 and 1967, and was responsible for the Race Relations Act of 1968.

In 1972, she was awarded an OBE for her work in education and community relations, and was appointed DBE in 1992 – making her the first Black British Dame.

She was the first Black woman to be appointed as a governor of the BBC, and was the chair of Mayor’s Commission on African and Asian Heritage in 2005.

She was instrumental in the creation of the North Atlantic Slavery Gallery and the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool.

She also served as a trustee of the National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside (now known as the National Museums Liverpool), was a governor at the British Film Institute, and was the first patron of the Black Cultural Archives.

Dr Paul Stephenson OBE (6 May 1937 – present)

Paul Stephenson, Credit: Prachatai

Paul Stephenson OBE is a community worker and civil rights campaigner.

Stephenson was born in Rochford, Essex in 1937 to a West African father and a British mother.

Stephenson worked in the Royal Air Force from 1953 to 1960, and gained a Diploma in Youth and Community Work.

In 1963, Stephenson led a boycott of the Bristol Omnibus Company colour-bar over its policy of not employing Black or Asian drivers or conductors.

In 1964, Stephenson refused to leave a pub until he was served, resulting in him being prosecuted for failing to leave a licensed premises.

Stephenson’s activism helped pave the way for the Race Relations Act 1965.

In the 1970s Stephenson became a friend of Muhammad Ali, setting up the Muhammad Ali Sports Development Association which encouraged children of colour to participate in forms of sport they were underrepresented in, such as tennis or angling.

In the 1970s and 1980s Stephenson worked at the Commission for Racial Equality and the Press Council, with a focus on diversifying the British media, and non-racist reporting on ethnic minorities.

Today, he is the Freeman of the City of Bristol, and received an OBE in 2009.

Doreen Lawrence, Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon, OBE (24 October 1952 – present)

Baroness Lawrence entered public life following the racist murder of her son. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Doreen Lawrence is a campaigner.

She was born in Jamaica in 1952, and arrived in the UK at the age of nine.

Lawrence entered public life following the racist murder of her son, Stephen Lawrence, in 1993.

She began campaigning, claiming that the police were not conducting the investigation into his death properly due to racism and negligence.

Lawrence founded a charity in memory of her son – the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust – in 1998, which campaigns against inequality in all its forms.

In 1999, the circumstances around Lawrence’s death were investigated after a judicial inquiry was established by the then home secretary, Jack Straw.

The inquiry was chaired by Sir William MacPherson. His findings were published in the landmark MacPherson Report, which found that there was “institutional racism” in the Metropolitan Police. The publication served as a watershed moment when it came to racism in policing in the UK.

In 2013, Lawrence was made a life peer in the House of Lords, becoming Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon. She is a member of both the council and board of human rights group Liberty, and is a patron of the hate crime charity Stop Hate UK. She also sits on panels within the Home Office and police service.

On 24 April 2020, Lawrence was appointed as Race Relations Advisor to the Labour Party.

Diane Julie Abbott (27 September 1953 – present)

Diane Abbott entered the House of Commons when there were no sitting Black MPs. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Diane Abbott is a British politician.

She was born in London to a British Jamaican family in 1953.

The daughter of a nurse and a welder, Abbott studied History at the University of Cambridge before joining the Home Office in 1976 as a civil servant.

After the Home Office, she become a Race Relations Officer at the National Council for Civil Liberties in 1978.

In 1982 she was elected to the Westminster City Council, and in 1987 she was elected as a Member of Parliament for Hackney North and Stoke Newington – making her the first Black woman MP to sit in the House of Commons.

She entered the House of Commons when there were no sitting Black MPs.

Abbott has been a staunch advocate for the rights of Black people in the UK, and has supported abortion rights.

She has criticised the government’s involvement in Saudi Arabia, and has been a fearless advocate on justice for the victims of the Windrush Scandal.

Patricia Scotland, Baroness Scotland of Asthal (19 August 1955 – present)

Baroness Patricia Scotland became the first Black woman to be appointed to the Queen’s Counsel. Credit: Commonwealth Secretariat

Baroness Patricia Scotland is a lawyer and politician.

Scotland was born in Dominica, with her family emigrating to the UK in 1957 when she was two years old.

She read law at the University of London, and was called to the bar in the Middle Temple in 1977, and called to the Dominican bar in 1978.

She became the first Black woman to be appointed to the Queen’s Counsel in 1991, and founded 1 Gray’s Inn Square barristers chambers.

In 1994, she was named Millennium Commissioner, and was a member of the Commission for Racial Equality.

In 1997, she was elected as Bencher of the Middle Temple, became a judge in 1999, and was raised to the Privy Council in 2001.

She has a life peerage on a Labour Party list of working peers, and was created Baroness Scotland of Asthal in 1997.

In June 2007, she was appointed Attorney General by Prime Minister Gordon Brown – and was the first woman to hold the office since its foundation in 1315.

Scotland has received an honorary degree from the University of Westminster for services to law, government, social justice, and international affairs.

Scotland was elected as Secretary-General of the Commonwealth Nations in 2015, and is the first woman to hold the post.