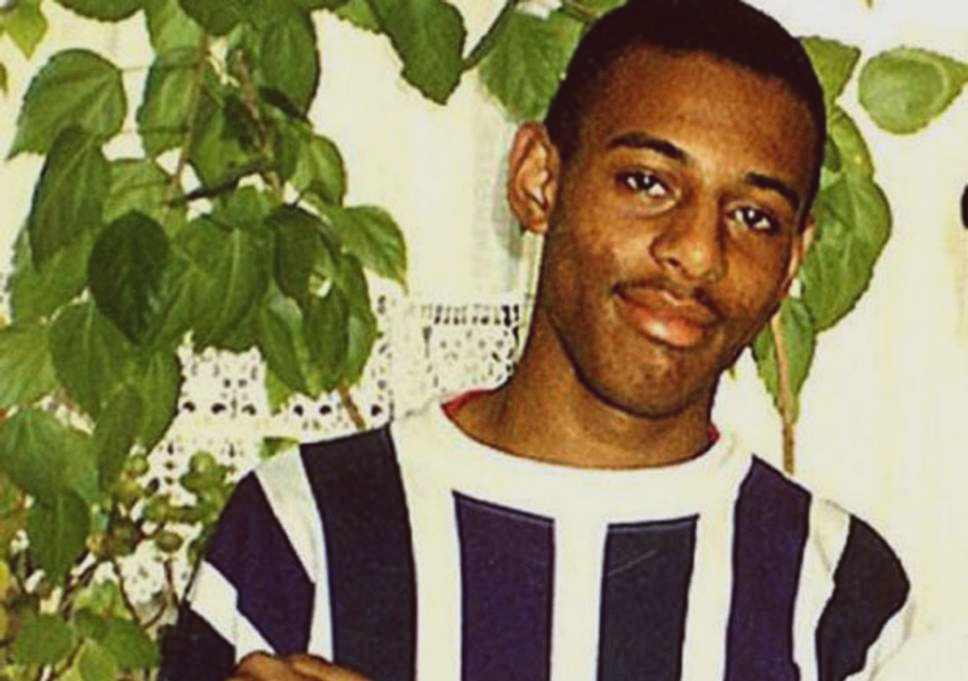

On the evening of 22 April 1993, Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death in Eltham, south east London. He was 18 years-old and black. His murder was sudden, unprovoked and motivated by racism.

The five prime suspects – Neil Acourt, Jamie Acourt, Luke Knight, Gary Dobson and David Norris – were white. After an unsuccessful private prosecution and inquest, they had not been convicted for the crime.

Four years after Stephen’s murder, the then-Labour government held a public inquiry into Stephen’s murder, chaired by former High Court judge, Sir William Macpherson. The Inquiry’s final report changed the trajectory of race relations in the UK. On the 20th anniversary of the publication of the Macpherson report, published on 24 Feb 1999, we look at how society has changed.

Background

The Lawrence family complained that the Metropolitan Police Service had botched the investigation into Stephen’s murder. The Inquiry was set up to investigate the matters arising from Stephen Lawrence’s murder and the Met Police’s investigation. Its scope was vast. The Inquiry sat for 59 days, received evidence from 88 witnesses and produced more than 100,000 pages of documents. The Inquiry made 70 recommendations to improve the police’s investigation procedures, tackle racism within the force, and repair the relationship between the police and ethnic minority communities.

The Inquiry Found The Met Police To Be ‘Institutionally Racist’

1981’s Brixton riots were partly caused by aggressive Metropolitan Police stop and search tactics Credit: Wikimedia Commons

1981’s Brixton riots were partly caused by aggressive Metropolitan Police stop and search tactics Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Inquiry’s most significant conclusion was that the Met Police was ‘institutionally racist’. This did not mean that every officer held racist views, or that there were weren’t upstanding individuals in the police force. Rather, the Inquiry defined ‘institutional racism’ as: “the collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin.”

Such racism was not only explicit, but also manifested itself in covert ways, such as racial stereotypes, ignorance and unwitting prejudice. As Doreen (now Baroness) Lawrence said during the Inquiry: “Racism is done in a way that is so subtle. It is how they talk to you… It is just the whole attitude…”

Racism is done in a way that is so subtle. It is how they talk to you.

Doreen Lawrence (now Baroness Lawrence)

For Stephen’s murder investigation, the charge of institutional racism meant that the Met Police had failed to investigate Stephen’s murder as diligently and seriously as they should have, because Stephen was black. In 2013, we would discover that a former undercover police officer, Peter Francis, was tasked with discrediting the Lawrence family during the murder investigation.

At the time, some commentators argued that there was no evidence to support the Inquiry’s conclusion that the Met was institutionally racist. Such claims were inaccurate. The Inquiry gathered a range of evidence from academics, community organisations and witnesses. The Inquiry found, for example, that Duwayne Brooks, Stephen’s friend who survived the attack, was racially stereotyped and treated with suspicion by the police during the investigation.

Racist stereotyping by the police was found to be a core reason for the disproportionate stop and search rates of the black population.

Despite evidence that Stephen’s murderers yelled “what, what, n*gger” before stabbing him to death, many junior police officers denied that Stephen’s murder was racially motivated. None of the officers questioned during the Inquiry had received racial awareness training in their career. Racist stereotyping by the police was found to be a core reason for the disproportionate stop and search rates of the black population.

The Inquiry Led To Important Changes To The Law

Credit: Flickr

Credit: Flickr

Ultimately, the Inquiry and Sir William Macpherson recognised the need for change. The Inquiry concluded that every institution in the country had a duty, “to examine their policies and the outcome of their policies and practices to guard against disadvantaging any section of our communities.”

After the Inquiry, there were some important changes in UK law. These changes provided some tools to combat racism at the structural level and uphold human rights. The Human Rights Act 1998, which came into force in October 2000, provided a powerful tool to hold public authorities – including the police – to account for failing to conduct effective investigations of certain crimes.

Parliament passed the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000, which prohibits racial discrimination by public authorities, including the Police.

Furthermore, Parliament passed the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000, which prohibits racial discrimination by public authorities, including the Police. The Act also introduced a race equality duty, which required public authorities to have due regard to eliminate unlawful discrimination and promote equality of opportunity. This equality duty was later implemented in the Equality Act 2010, which protects people from being discriminated against in the workplace and other public institutions.

Still, a truly anti-racist society cannot be built by laws alone. Laws must be supported by the political will and resources to transform public institutions. In this respect, the police still has room for improvement. Consider that black and minority ethnic people continue to be statistically under-represented in the national police force. Despite making up 13% of the population, only 6% of police officers are of minority ethnic descent.

A truly anti-racist society cannot be built by laws alone.

Furthermore, there are serious questions on the accountability of the police in relation to deaths in custody. Not a single officer has ever been successfully prosecuted for manslaughter over a death in police custody, despite an unlawful killing verdict by a coroner. This is despite the fact that young black men are twice as likely to die after being subjected to force or restraint by the police in custody, compared to their white counterparts.

In April 2018, UN human rights experts commented that the disproportionate number of such deaths, “reinforce the experiences of structural racism, over policing and criminalisation of people of African descent and other minorities in the UK.”

The police still has a vast amount of work to develop a racially representative force, improve its accountability and build a fairer policing strategy that does not alienate ethnic minorities.

The recent controversy over the Met Police’s Gangs Matrix database is a further example of such over policing. The Met Police was found to have illegally racially stigmatised and profiled black people. In the database, 78% of people deemed responsible for gang violence in London are black. However, according to an Amnesty International report, black people commit only 27% of serious youth violence associated with gang activity. These examples show that the police still has a vast amount of work to do, in developing a racially representative force, improving its accountability to the public and building a fairer policing strategy that does not alienate ethnic minorities.

The Inquiry Changed The Way Police Investigate Racist Crimes

Credit: Flickr

Credit: Flickr

Racist hate crimes violate our human rights and offend our dignity. Under the Human Rights Convention, the state is legally obliged to investigate and uncover any racist motives in hate crimes. A failure to adequately investigate racist motives has been found, in some cases, to have violated the human rights of the victims.

The Inquiry found that the murder of Stephen Lawrence was not effectively investigated by the police. It therefore made a variety of recommendations to the Metropolitan Police and government, to improve the reporting, recording, investigation and prosecution of racist crimes.

The Inquiry found that the murder of Stephen Lawrence was not effectively investigated by the police.

The Inquiry recommended that the double jeopardy rule should be abolished. The rule against double jeopardy law prevented a person from being tried twice for the same crime. The Inquiry recommended that the courts should consider waiving this rule, where “fresh and viable evidence” came to light, as it risked causing injustice.

Such reform was important in the Lawrences’ case. In 1996, their private prosecution against Neil Acourt, Luke Knight and Gary Dobson collapsed. At the time, it looked like they could never be prosecuted again. Four years after the Inquiry however, Parliament changed the law by passing the Criminal Justice Act 2003. This reform directly led to the successful prosecution, in 2012, of two of the original suspects, Gary Dobson and David Norris for Stephen’s murder.

A 2018 report from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary found that in 89 out of 180 hate crime cases it reviewed, the police’s response was inadequate.

Furthermore, the College of Police have now developed standard operational guidance for police investigations of hate crimes. The Met Police describes hate crime as one of its “highest priorities”, and has deployed over 900 specialist hate crime investigators in communities across London.

Yet, in the current social climate, there has been an increase in recorded hate crimes. From 2017 to 2018, an estimated 76% of recorded hate crimes in England and Wales were racially motivated. The police also need to develop a more consistent approach towards tackling hate crimes. A 2018 report from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary found that in 89 out of 180 hate crime cases it reviewed, the police’s response was inadequate.

The Inquiry Called For Reform Of Police Use Of Stop And Search

Credit: Eye DJ Flickr

Credit: Eye DJ Flickr

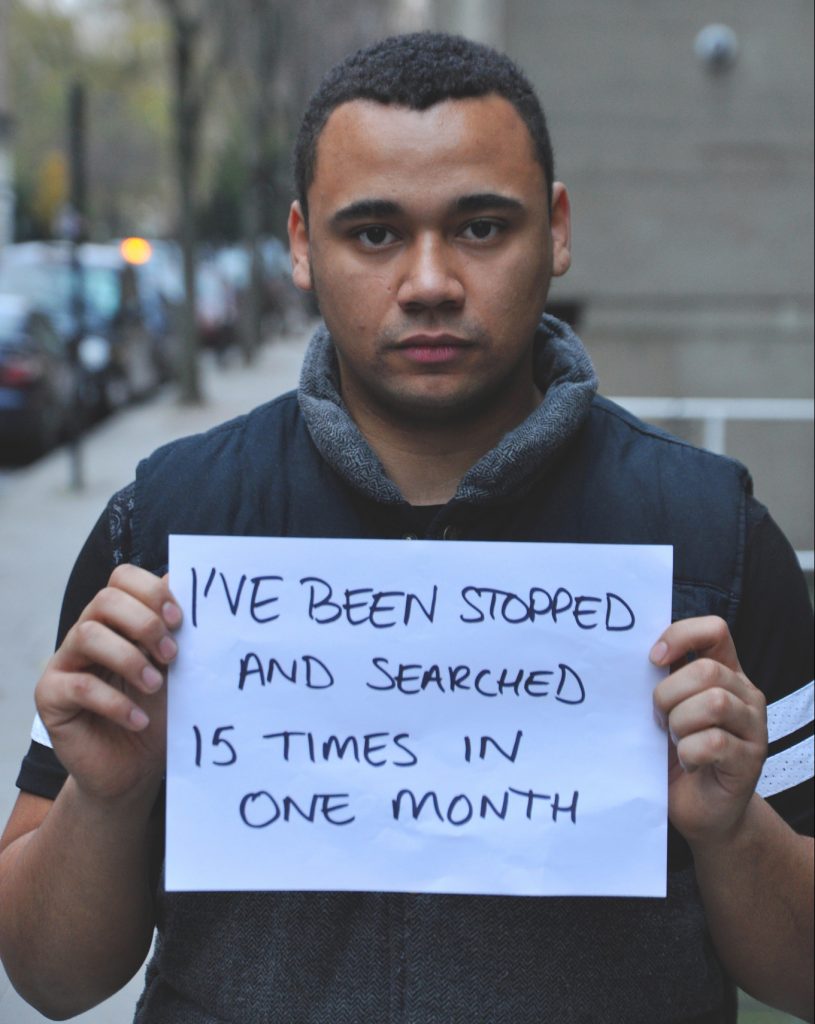

Stop and search is a critical human rights issue. Stop and search practices by the police interfere with a person’s privacy. Under Article 8 of the Human Rights Convention, everyone has a right to have their private life respected. It means a person’s privacy can only be interfered with in limited circumstances. There must be appropriate safeguards in place to ensure the police do not abuse their power.

The Inquiry recognised the black community’s feelings of “distrust and loss of confidence” caused by the Met Police’s disproportionate and racially discriminatory searches.

The Inquiry noted that stop and search had a “genuine usefulness” in preventing and detecting crime. However, it also recognised the black community’s feelings of “distrust and loss of confidence” caused by the Met Police’s disproportionate and racially discriminatory searches. The Inquiry therefore recommended that the police take measures to reduce the amount of discriminatory stop and searches they carry out.

In particular, the Inquiry recommended that the police record all stops and stops and searches, monitor the records of stops, and ensure that the statistics are published.

Some progress has been made. A report from the Equality and Human Rights Commission in 2016 found that the overall use of stop and search powers had decreased between 2010-2015. As of 2016-2017, the use of stop and search in England and Wales fell to a record low of around 304,000. Nonetheless, disproportionate stop and search rates still persist. In 2016-2017, in England and Wales, black people were almost nine times more likely than white people to be stopped and searched by the police.

Supporters of stop and search argue that it is an important tool to tackle crime, especially those involving knives and gang violence. For these reasons, in the case of Roberts v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis and Another, the UK Supreme Court asserted that young black and minority ethnic people would benefit most from the police’s use of random, “suspicionless” stop and search powers.

The police and the government have not done enough to reduce disproportionate stop and searches against the black population in London and the UK.

However, current statistics challenge these claims. In 2017, researchers from the Centre of Crime and Justice Studies found there was limited evidence that stop and search was effective in reducing crime. Furthermore, a report from the Guardian published in 2019, showed that police searches of black people in London – particularly for carrying weapons – were statistically less likely to result in an arrest than those police searches of white people.

Meanwhile, government measures such as the voluntary Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme launched in 2014, have struggled due to the police’s failure to comply with its requirements. In light of this, black people in England and Wales have statistically lower levels of confidence in their local police than other ethnic groups. The general picture remains unimpressive 20 years after the Inquiry. Both the police and the government have not done enough to reduce disproportionate stop and searches against the black population in London and the UK.

The Inquiry Highlighted Education As Key In Preventing Racism

Stephen’s mother Baroness Lawrence giving evidence to the Home Affairs Committee this week

The Inquiry also addressed the prevention of racism through education. The Inquiry acknowledged that eradicating racism was not just the responsibility of the police, but also of the education system. The Inquiry observed: “Improved understanding and attitudes will certainly help to prevent racism in the future…”

Therefore, the Inquiry made recommendations aimed to amend the National Curriculum in valuing cultural diversity and preventing racism.

Education is a vital human right. Protocol 1, Article 2 of the Human Rights Convention guarantees people the right to an education, free from racial discrimination. Under that Convention, disadvantaged and vulnerable ethnic minorities are entitled to have special protection for their education rights.

The UK government has made little progress in building an anti-racist curriculum.

Unfortunately, the UK government has made little progress in building an anti-racist curriculum. The National Curriculum framework in England requires pupils to learn about “diverse national, regional, religious and ethnic identities” and the “need for mutual respect and understanding”. Still, this provision is very general, and only applies to citizenship lessons at Key Stage 4, when pupils are aged between 14 and 16. There are no detailed measures for anti-racism education in the National Curriculum from Key Stages 1 to 3.

Meanwhile, discrimination is alive in schools. Reports of hate crimes in schools across the UK increased by 89% during the Brexit campaign in May 2016. Black Caribbean pupils are three times more likely to be permanently excluded from schools than other children. Pupils of a Gypsy/Roma and Traveller background were around six times more likely to be excluded compared to all pupils.

The disparities in the treatment of ethnic minority pupils, along with the rise in reported racist incidents, should be of great concern to us. How young people learn to treat each other, and in turn how they are treated by educational authorities, will profoundly affect their perspectives as adults. The UK education system therefore can take a more active role in preventing the growth of racist attitudes between pupils and teachers alike.

Twenty Years On: Still No Justice For Stephen

Twenty years ago, the Home Secretary Jack Straw stated that he wanted the Inquiry’s report to act as a ”catalyst to permanent and irrevocable change” across the whole of society. Twenty years later, the effects of the Inquiry have been mixed. The Inquiry’s report increased the public’s awareness of institutional racism and its grave effects on ethnic minorities.

We have also seen an overhaul of human rights and equality legislation. However, disproportionate stop and search policies persist, and police accountability for deaths in police custody remains poor. Furthermore, the education system has not truly fostered an anti-racism strategy for future generations of British children.

Above all, three of Stephen’s suspected murderers have not been convicted for their crimes.

Until they are tried and convicted, then justice for Stephen Lawrence will remain incomplete. Until the problems that the Inquiry raised about our institutions are solved, then racial equality in British society is a work-in-progress.

Featured image credit: Telegraph video report on Stephen Lawrence’s murder via YouTube