In just a few days time, MPs will vote on whether the government should retain its “unprecedented powers” under Coronavirus Act 2020 for another six months. A lack of proper scrutiny threatens our democracy, could cost lives, and could allow conspiracy theories to dominate the narrative, writes Nadine Batchelor-Hunt.

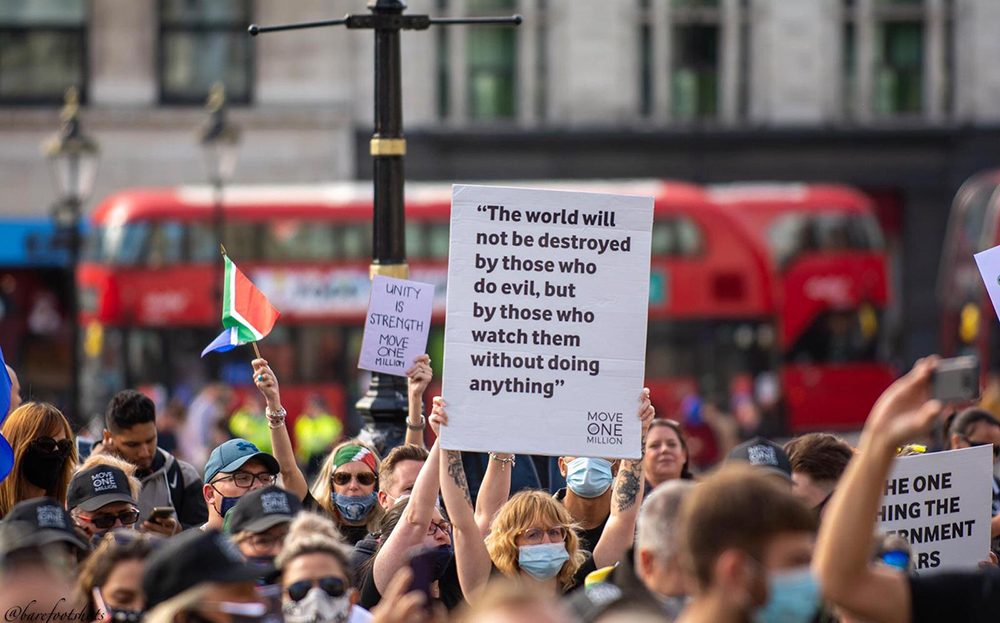

In recent months there have been growing media reports of anti-lockdown protests, supported by conspiracy theorists, in which demonstrators have made bizarre and outlandish claims. The conspiracies – unsupported by scientific evidence – are often couched in terms of “civil liberties” and “freedoms”.

They speculate that Covid-19 is part of an insidious plan designed to control the population. Be it the anti-5G movement, anti-vaxxers, or the sinister rise of QAnon, many among them have argued that the government’s actions on Covid-19 are nothing to do with a virus which has claimed more than 40,000 lives in the UK.

Debates about other restrictions are also rife among fringe right-wing groups – who have managed to politicise the wearing of masks, some going as far as to suggest mask-wearing is the start of another Holocaust, despite the fact scientific evidence shows mask wearing helps prevent the spread of the virus. Rightly, these ideas have generally been debunked and dismissed – although, disturbingly, some seem to be gaining steam in the UK.

However, it is possible to acknowledge these conspiracy theories are baseless while also recognising that concerns about restrictions on our civil liberties are valid.

As highlighted in a recent report by parliament’s joint human rights committee, the right to life has been “central” in the government’s response to the pandemic. Although it raised concerns over the government’s record of protecting disproportionately affected groups, such as older people, people with disabilities, and Black, Asian and minority ethnicity (BAME) communities.

Under Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the UK government and other public authorities have a legal obligation to take positive steps to protect people whose lives are at risk, including from Covid-19. However it is not an “absolute” obligation, which means the state may not always be able to fulfil it due to limited resources.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has introduced tougher restrictions. Credit: Number 10

What is patently clear, is that restrictions have curtailed many of the rights that, less than a year ago, we saw as immovable – including the right to protest, and the right to an education.

You now risk getting a £10,000 fine for organising a protest; the fine is unappealable, and an utterly life-changing figure for the average person. While I may fundamentally disagree with anti-vaxxer Piers Corbyn, the fact he was arrested and slapped with a £10,000 fine for protesting scares me.

The fact that our neighbours are being encouraged by the government to spy on us, which could result in gross invasions of our privacy, scares me. The fact that the government can make it illegal for us to see our loved ones scares me.

The fact that Prime Minister Boris Johnson, nonchalantly and with very few details, tells the nation the military may be rolled out to back up the police if we don’t follow the rules, scares me. The swift and unilateral implementation of curfews at the drop of a hat scares me.

Does that mean I don’t care about the virus? Of course not; to suggest that concerns about the virus are an either or game – you either back authoritarianism or you don’t care about Covid-19 – is a false dichotomy, and a dangerous one.

Police can hand out hefty fines for gatherings larger than six. Credit: fungaifoto

The government can lawfully take proportionate steps to interfere with a number of our rights – such as our right to liberty and our freedom to assemble – if necessary to protect lives amid the pandemic.

But all of this is happening with little, if any, scrutiny. I did not vote for this, and nor did you – yet we are having it forced upon us, for another six months or more. And, while some may celebrate this, I do not – that is not how a democracy works.

The legislation is rushed through so quickly MPs don’t even have a chance to ask questions about it. Nor has there been chance for proper debate regarding proportionality; life changing fines and criminal records for exercising what were, just a few months ago, basic civil liberties should not be passed without accountability or debate. Yes, there is an argument the government must move quickly in making laws to hinder the virus’ spread. But more than six months in to the pandemic, with no end in sight, we cannot afford to do away with scrutiny. And there has been little talk of the abuse of those powers by the police, nor on its shortcomings.

Police were found abusing their powers at the beginning of the pandemic, using drones to spy on citizens walking in secluded areas, and police enforcement of coronavirus restrictions has disproportionately affected BAME people. Not only this, but working-class people are seeing their livelihoods getting smashed up over and over again as we sink into the biggest recession in history and the furlough scheme winds up. And, while Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced another package of financial support, it is far less generous than the furlough scheme – and he said he “can’t save everyone”.

The UK is sinking into the biggest recession in history. Credit: pxhere

Which leads us onto the trade offs. As well as the human rights impacts of the pandemic response, the significance of which is hard to convey, the social and economic toll of Covid-19 restrictions are already beginning to show their effect.

Mental health issues have skyrocketed, and there are growing fears that cancers are being missed with around 350,000 fewer patients than normal referred for urgent cancer investigation.

Deaths at home are significantly above average for the same period last year, with over 10,000 excess deaths since mid-June, and NHS waiting lists have soared after treatments were cancelled in anticipation of the NHS being overwhelmed. Domestic violence reports have grown, and poverty is on the rise – with extreme poverty predicted to double by Christmas.

It is becoming clear that, in many areas of life, the consequences of the virus restrictions will last far longer than the virus. And, while for many sacrificing these areas is a cost they’re willing to take, for some it’s not: and their voices should be heard. There must be open and honest debate about these issues if we are to continue to call ourselves a democracy, and it is absolutely human – and fair – to have reservations about the government’s strategy.

There is growing pushback by some MPs, which is some comfort; the Joint Human Rights Committee, chaired by Harriet Harman, are pushing for amendments to the Coronavirus Act. Some of the amendments would include national and local lockdown regulations expiring within a week after being introduced unless approved by MPs and peers, new lockdown rules having a “proportionality assessment”, and fines and Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs) only being introduced if they can be appealed. But, elsewhere, peers in the House of Lords have expressed concern that the government have been ignoring their questions for months.

Social and economic strains could impact more people than the virus. Credit: Garry Knight

Ultimately, what was the best strategy when it comes to dealing with the virus will only be shown with time and hindsight in the years to come. Whether the long-term social, economic, and health trade-offs for the short-term will balance out in the long-term is simply impossible to know.

But we don’t need hindsight to know that preserving democracy should be a timeless and inalienable right, and can never be tossed away. Because the minute human rights become a privilege, not a right, we enter dark territory – and set dangerous precedents. And you don’t have to be a hard-right libertarian, or a 5G conspiracy theorist, to see that.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.