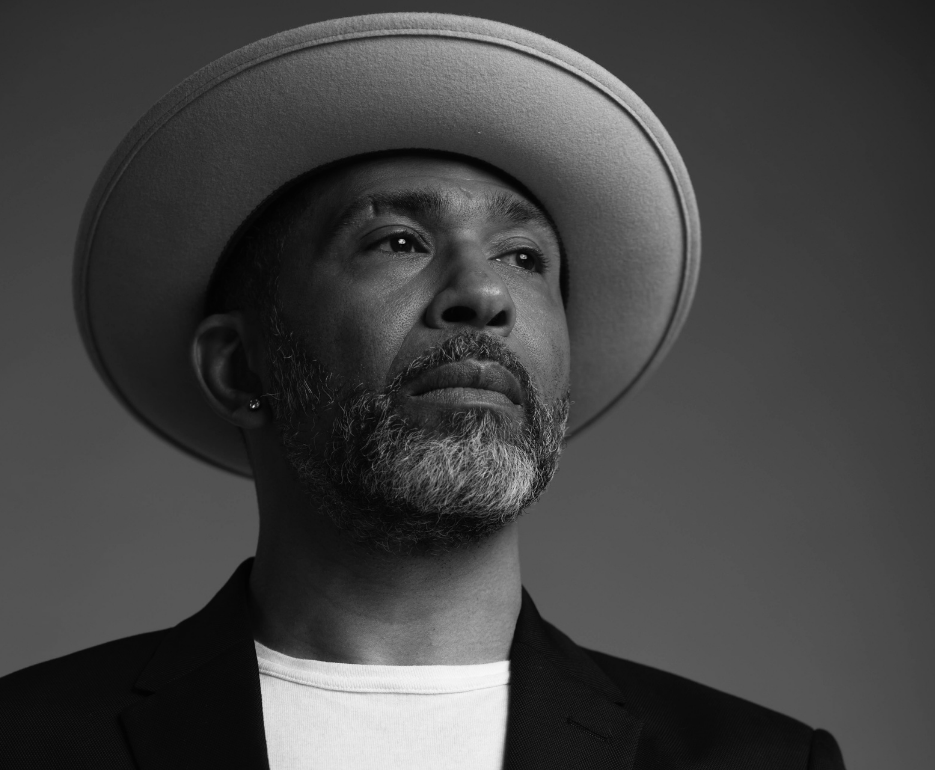

For over 30 years, Marc Thompson has campaigned for HIV awareness including, to make pre-exposure medication (PrEP) available on the NHS. Now, alongside charities, Marc calls for inclusivity and explains how as a society, we can begin to break down barriers to ensure those left out of the conversation are included.

Speaking about broadening the lens on conversations around HIV, Thompson said:

“I went to a couple of events. And I was struck by a couple of things: I was usually one of the only people of colour, telling the story from a historical perspective. And there were usually only one or two women if any at all. That really frustrated me because I knew that there were these really rich narratives that didn’t just belong to cisgendered white men of a certain age: as much as I know that those stories are important. I wanted to broaden the lens.”

Fulfilling this ambition is Thompson’s podcast, We were always here. It started as an oral history project, but has since become a digital tapestry and flagship for inclusivity in conversations around HIV. We were always here looks at the history of HIV and human rights in the UK from new perspectives.

Thompson stated: “My idea was really simple. I wanted to tell the story through voices that have just never been heard. So women, people of colour, young people who are born with HIV, the trans community and sex workers, everybody that was usually on the edges are included.”

The podcast has been recognised for including the stories of people who were affected whilst fighting the epidemic, such as clinicians and volunteers.

He added: “It’s about telling stories so that we have a richer perspective of everything that happened, it’s really important to honour those people.”

Access to healthcare

Across health and social care, in the UK, like many public institutions, systemic racism and sexism, continue to play a major role in people’s health and their experiences when accessing healthcare.

Thompson explains that systemic and institutionalised racism must be acknowledged, to make progress.

Thompson said: “We can’t address HIV stigma until we address the fact that HIV stigma is very often wrapped up in racism, homophobia, sexism, and misogyny. And so until we tackle it from a much more adult, radical view, we’re getting nowhere at all.”

Women of colour, including migrants, have been particularly stigmatised and continue to face barriers when trying to access adequate healthcare in the UK.

In 2002 the Department of Health introduced new regulations to block failed asylum seekers and undocumented migrants from receiving HIV treatment from the NHS. In 2005, the House of Commons Health Select Committee intervened with recommendations that the restrictions should be lifted. However, barriers to healthcare remain the main factor in HIV treatment.

Thompson stated: “In the UK Black women are the second largest group impacted by HIV. They experience higher rates of stigma, due to the intersection of race and gender and continue to be at the bottom of reproductive health charts, you know, all of these things impact people’s lives today.”

The right to health is protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), to which the UK is a signatory. This means the UK is bound by international law to protect the right to health.

Breaking down barriers

Thompson is dedicated to cultivating spaces that hold voices and allow them to be heard. Speaking to EachOtherabout We were always here, he explained how barriers are systemically embedded in our society:

“It wasn’t just about hearing the stories of these women with HIV, but it also then to answer questions like: why are there not more women in leadership roles? Why are there not more women running organisations in this country, around HIV and in other health settings? Women are still pigeonholed into working only on women’s health issues. And we needed to change that.”

The UK government has stated that it is dedicated to eliminating HIV transmission by 2030, but this depends upon sustaining prevention efforts and further expanding them to reach all at risk.

The UK Health and Security Agency (HSA) said: “Thanks to modern antiretroviral treatment, people with HIV can expect to live long healthy lives. However, too many people are diagnosed with late-stage HIV infection which means they have been living with undiagnosed HIV infection for around three to five years. These people have a tenfold risk of death within a year of diagnosis compared to people diagnosed promptly.”

The HSA has previously spoken about its concerns that additional barriers could have for people trying to access healthcare during the coronavirus pandemic and now, in a post-Covid environment.

Speaking about the global goal to end transmission, Thompson said: “In the next 40 years, we are still going to have people who are living with HIV and they will still have needs and requirements. Even if we end transmission in the UK, there will still be transmissions elsewhere, whether that be in Eastern Europe, Africa, or parts of South America. We need to ensure that there continues to be equity around the response globally, especially around access to safe medications.”

We live in a hostile environment

In the UK the NHS is under pressure from Covid-induced backlogs and threats of privatisation, but it is clear that to make progress, the UK needs accessible services, including sexual health.

“We operate in a hostile environment around migration. As a migrant person or person of colour, you could be worried about going to sexual health services, you don’t understand the NHS, you think it might not be free of charge,” Thompson said.

He continued: “And then we also have a sexual health service, which is under immense pressure and one that is facing budget cuts. We have an NHS that’s on its knees. So, all of these factors come together to increase the barriers, which enable those who are most vulnerable to access, health care, and then sexual health care.”

The HSA’s pledge to end transmission by 2030 focuses on preventing, testing, treating and retaining, to ensure fair access to and uptake of HIV prevention programmes. The government has promised to scale up HIV testing in line with national guidelines and has stated that those testing positive must receive rapid access to care and treatment. Another priority will be to retrain staff so that everyone receives the support they need to remain in treatment. This includes improving the quality of life for people living with HIV and addressing the stigma through awareness raising and education.

Speaking about the future beyond 2030, Thompson said: “By then we may not have a cure, we may have injectables, we may have all-new treatments, but in the next 40 years I want to ensure that those people that need the most have first access to them.”

For more information and useful resources on HIV and human rights in the UK, check out our spotlight on the topic here.