The Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition Censored! Stage, Screen, Society at 50 explores censorship in the arts and freedom of expression in creative spaces as it marks 50 years since the Theatres Act 1968 came into force, abolishing censorship in the theatre.

It might be difficult to imagine now, but between 1737 and 1968 no play could be staged without first being approved by the Lord Chamberlain – the most senior member of the Royal household.

A Thin-Skinned Prime Minister

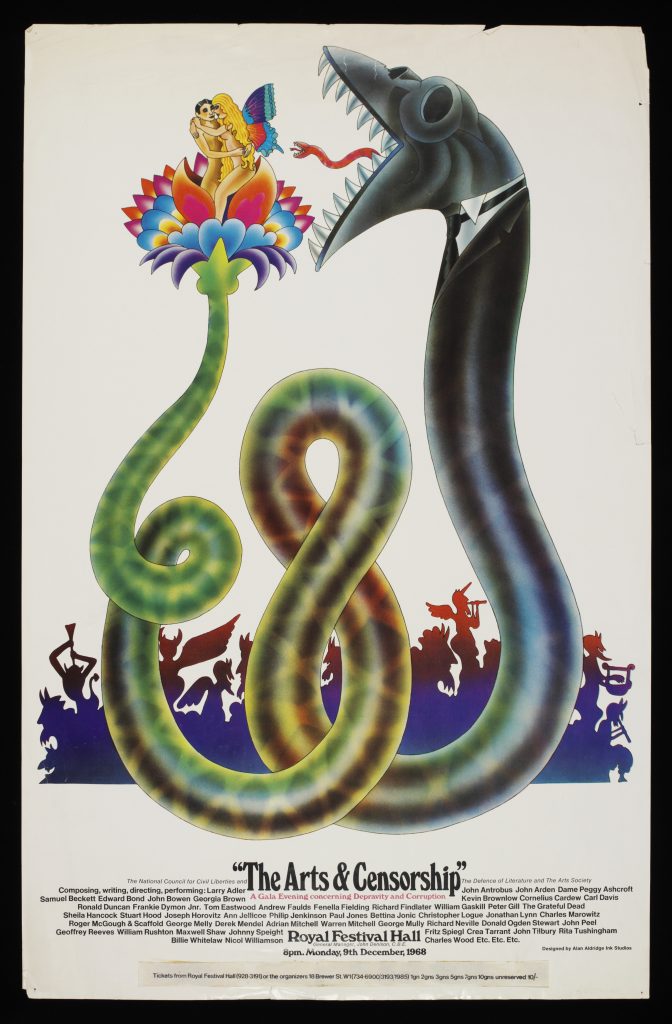

Poster for The Arts & Censorship gala at the Royal Festival Hall, 1968 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Poster for The Arts & Censorship gala at the Royal Festival Hall, 1968 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Looser forms of censorship predated 1737 but as the V&A explains, the impetus for the tough new law was an opera by John Gay, The Beggar’s Opera.

The opera repeated well-known accusations of corruption against incumbent Prime Minister Robert Walpole. The thin-skinned Prime Minister responded by introducing the Licensing Act 1737, essentially censoring what could be said about the government on stage.

As a member of the Royal household, the Lord Chamberlain was particularly concerned with preventing the monarch and government being mocked or ridiculed. He (and it always was a he) also removed references to sex – especially homosexuality.

By the mid-20th century censorship in the theatre was itself being mocked and ridiculed. A parliamentary report in 1967 recommended – against the wishes of the Lord Chamberlain – that censorship in the theatre be abolished, and the Theatres Act 1968 soon followed.

No ‘Arses’ or ‘Sods’

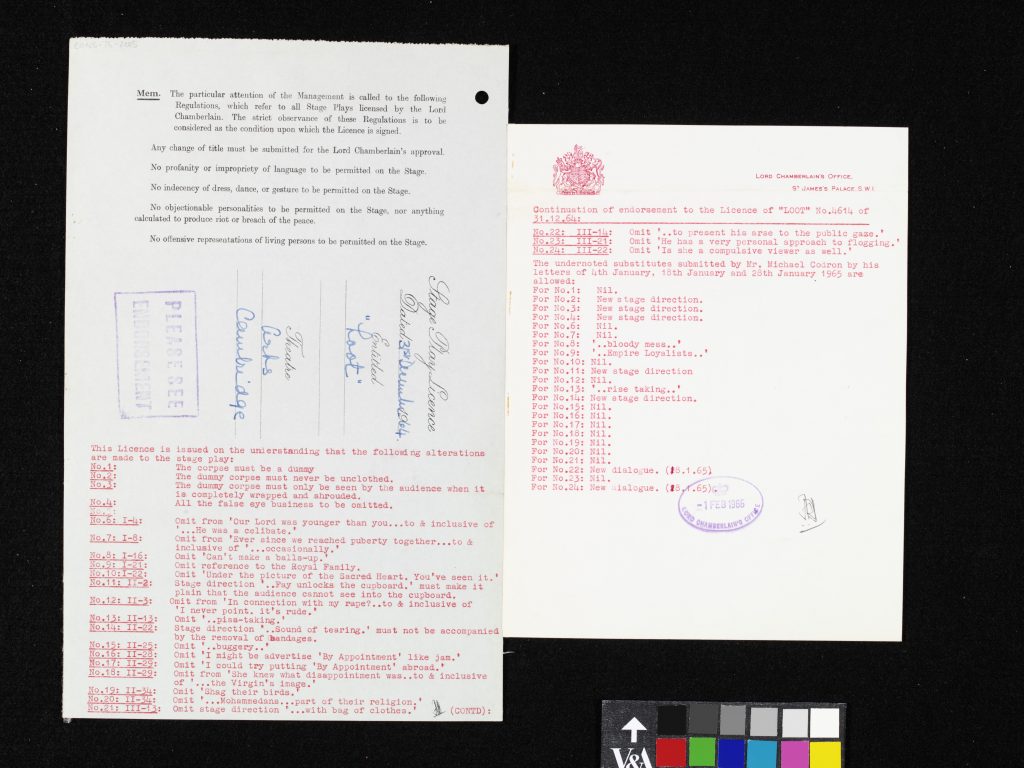

Licence from the Lord Chamberlain for Loot by Joe Orton, 1964 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Licence from the Lord Chamberlain for Loot by Joe Orton, 1964 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The display at the Victoria and Albert Museum includes a number of fascinating artefacts – including a letter from the Lord Chamberlain explaining he would not allow the use of words including ‘arse’ or ‘sod’ in the 1965 play Saved.

In total the Lord Chamberlain required over 50 amendments to be made to the script. The playwright refused to cut two scenes, leading to the play being banned. It was however, performed in private.

The display also reminds us that censorship in the arts persists beyond 1968.

The Theatres Act 1968 didn’t completely end state control of the performing arts. In fact, it created two criminal offences: giving an obscene performance of a play contrary to section 2 Theatres Act 1968; and of provoking a breach of the peace by giving a public performance of a play, under section 6 Theatres Act 1968.

There is a defence against the section 2 offence on the basis that the performance in question is justified as being for the public good on the ground that it was in the interests of drama, opera, ballet or any other art, or of literature or learning.

the BBC refused to play the single because its lyrics highlighted violence against gay people.

Music has also been subject to censorship over the years. The display features the cover art from Tom Robinson’s single: Glad to be Gay.

It reached no.18 in the UK Singles Charts in 1978 but the BBC refused to play it because its lyrics highlighted violence against gay people.

Censorship of Theatre Happens in 21st Century Britain Too

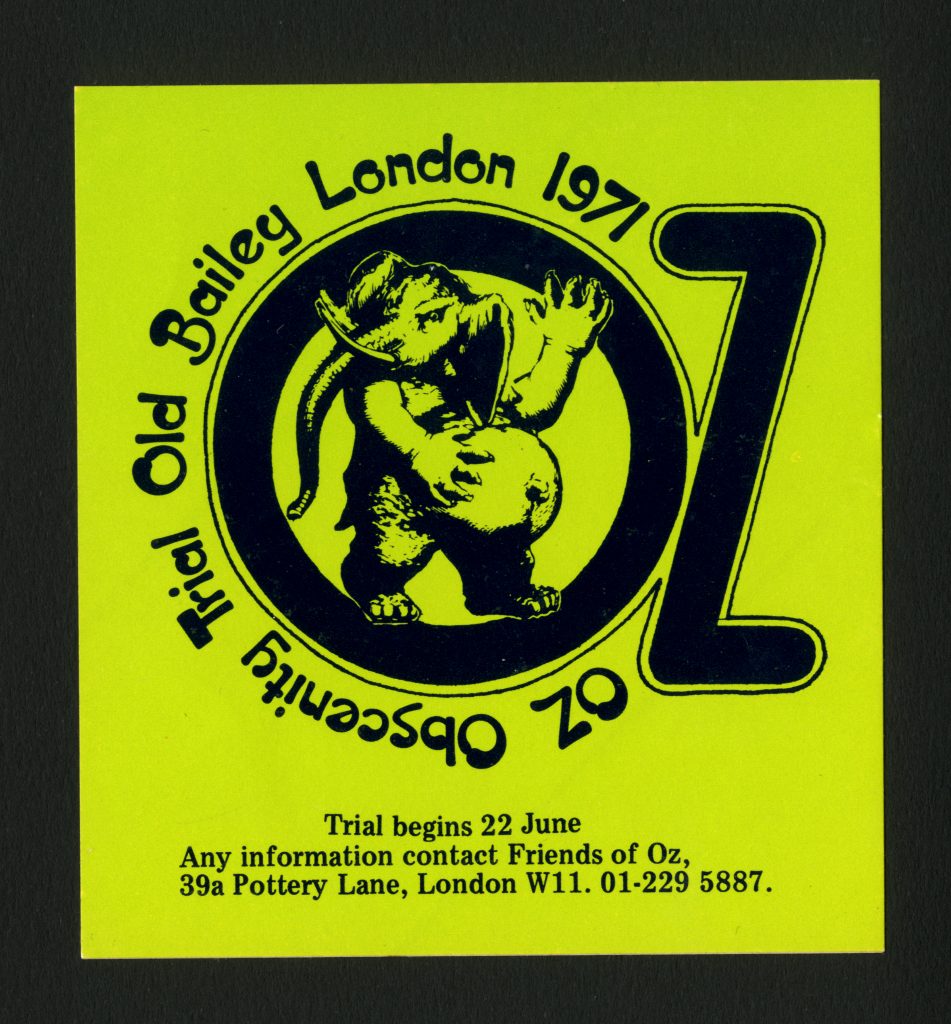

OZ magazine obscenity trial flyer, 1971 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

OZ magazine obscenity trial flyer, 1971 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

More informal censorship of the theatre persists today, as the display makes clear.

The display highlights Behzti – a play depicting a rape in a Sikh temple, which was cancelled in 2004 following a riot.

And Exhibit B – a live installation designed to highlight the violence of slavery was withdrawn by the Barbican in 2014 after protests and accusations of racism.

In summer 2017 the play Homegrown – about radicalisation of young Muslims was cancelled amid ‘safeguarding concerns’ and worries about how it would be received on social media.

Of course censorship is not a uniquely British phenomena: the display notes that in the USA last year, a performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Ceasar was disrupted by protestors and lost corporate sponsors after depicting the assassination of a Roman emperor who bore many similarities to President Donald Trump.

I would have liked the V&A’s exhibition to have given a taste of censorship in other parts of the world too. For example, the film Christopher Robin has been banned in China because of President Xi Jingping’s sensitivity over jokes comparing him to Winnie the Pooh.

But, as an introduction into censorship in the arts in the UK, Censored! Stage, Screen, Society at 50 is excellent.

Censored! Stage, Screen, Society at 50 is at the V&A until 27 January 2019

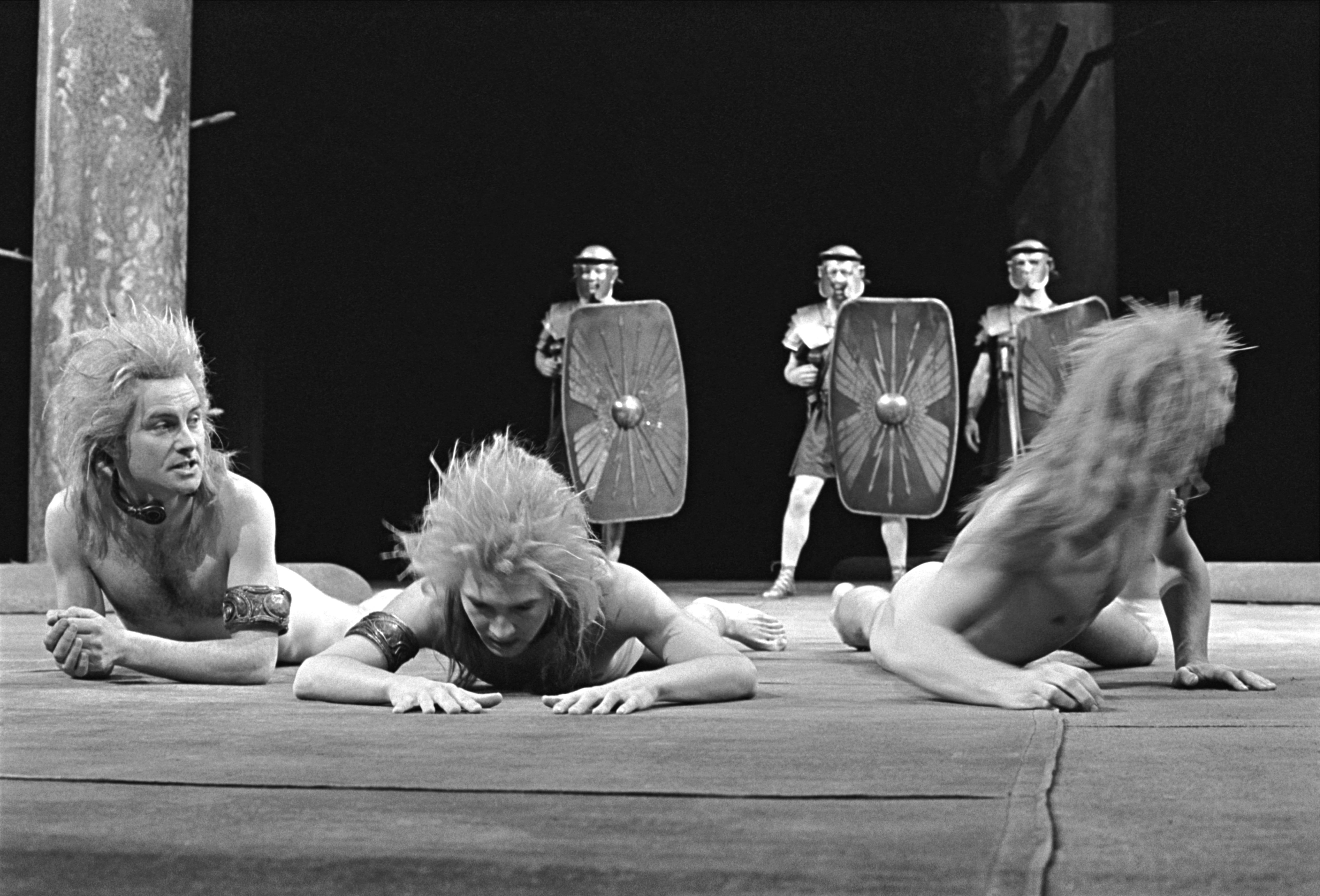

Featured image: Production photograph of The Romans in Britain, National Theatre, 1980

Credit: Douglas Jeffery Image copyright: © Victoria and Albert Museum