The so-called ‘Heartbeat Bill’, successfully pushed through the Texas legislature in September 2021, is the end of already weak legal protection for women’s fundamental rights in the American state.

While many may believe such challenges to reproductive rights could not be replicated here in the UK, our domestic legislation on abortion remains patchy, paternalistic and lacking in power. At best, UK law has successfully made abortion a safe, affordable procedure. At worst, it violates people’s rights under the Human Rights Act to be free from discrimination, enshrined in Article 14, and inhuman or degrading treatment, protected under Article 3.

Global evidence suggests that the actual rate of terminations remains the same, whatever the law on abortion. Where harsh laws exist, this simply means more women die from the complications of an illegal or unsafe termination. One in seven maternal deaths is caused by complications from an unsafe abortion, and in countries with strict abortion laws, this figure rises to 50% for all maternal deaths. This is despite evidence from the World Health Organisation (WHO) that legalisation and regulation can render it one of the safest possible medical procedures.

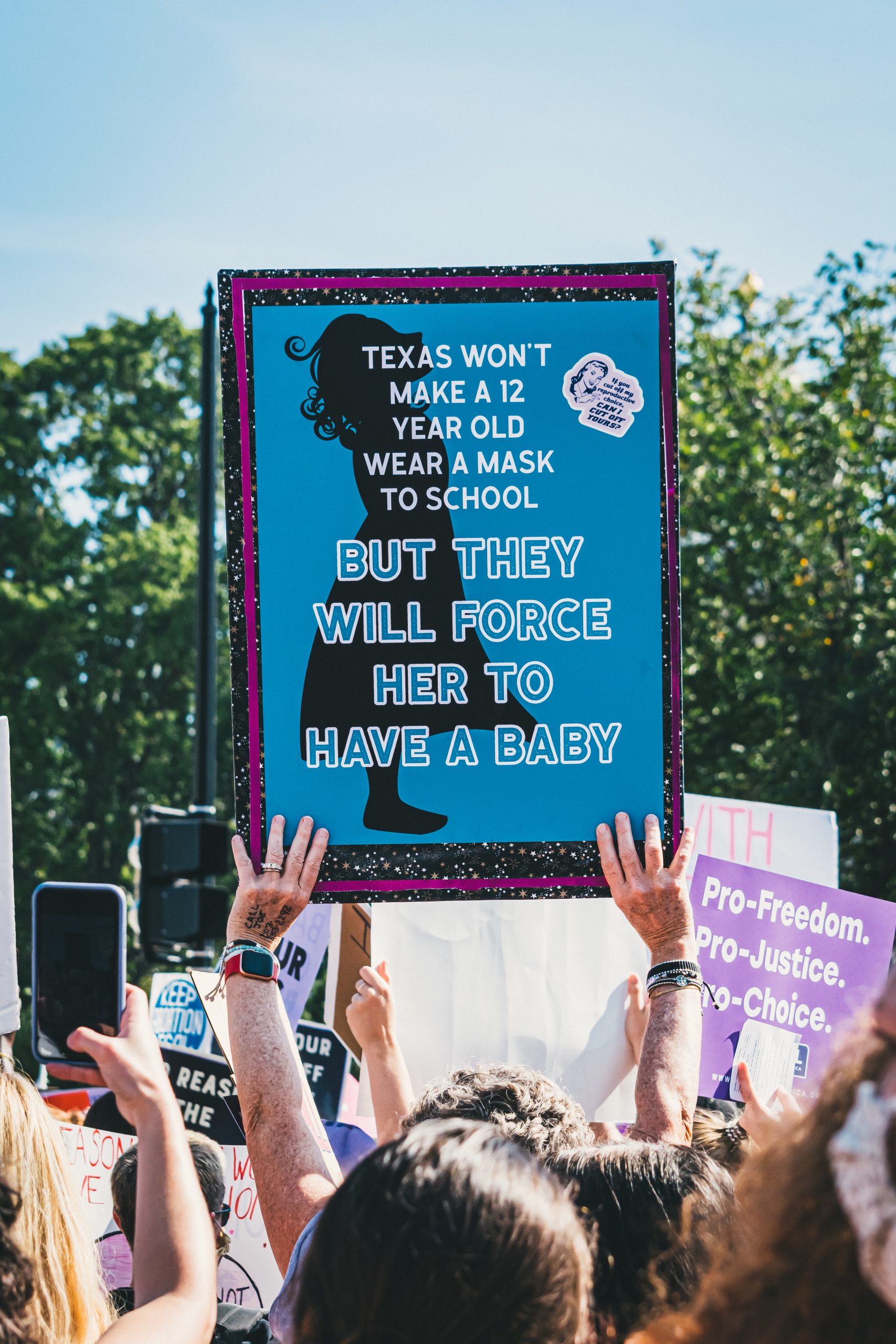

While an anti-abortion movement promoted and funded by the evangelical right has taken off in the US, in the UK we may believe our laws would prevent such opposition to people’s right to choose. In fact, the legal protection of the right to an abortion in the UK is neither immune from challenge nor beyond backlash. This is evidenced by the emergence of a visible anti-abortion protest movement outside UK abortion clinics, emboldened by its US counterparts.

History of UK Abortion Law

Credit: Francisco Venancio / Unsplash

‘Procuring a miscarriage’ was punishable by up to a lifetime’s penal servitude under the Offences Against the Persons Act 1861. After a period of increasing deaths at the hands of back-street abortionists, the passing of the Abortion Act in 1967 put an end to draconian punishments for people performing and accessing terminations. Though this allowed for some progress, it still offers relatively little legal protection to those choosing to terminate a pregnancy. The legislation exists to protect the doctor who performs the abortion, as long as he or she believes that the need for the procedure complies with the law’s specified conditions.

One in three women in the UK will have an abortion in their lifetime, making it one of the most common medical procedures a woman can undergo. Despite this, doctors retain legal status as the ‘gatekeeper’ of terminations. Two doctors must agree for the procedure to be in compliance with the law and any doctor may conscientiously object, unlike any other medical procedure.

Abortion is the single medical intervention presented in law as a moral quandary – despite the fact that in the over 90% of cases where terminations occur before 12 weeks of pregnancy, it comprises only taking two tablets. A so-called early medical abortion is a demonstrably safe procedure, and certainly safer than carrying a pregnancy to term – one of the most unsafe things a woman can do.

Credit: Gayatri Malhotra / Unsplash

Credit: Gayatri Malhotra / Unsplash

It may come as a surprise to some that women in the UK do not have the right to a termination on demand. There is perhaps a presumption that, despite the wording of the law, very few doctors would refuse a termination – meaning abortion access may naturally drift towards liberalisation.

Texas, Alabama, Idaho, Ohio and Tennessee in the USA are our warnings. The right to choose an abortion will not be fulfilled until it is available on request, without consideration for what lawyers and doctors believe may be an acceptable precondition for not carrying a pregnancy to term.

Although the Abortion Act put a stop to the scourge of unsafe ‘backstreet’ abortions, 54 years on its continued presence in the criminal code makes for stigmatisation and discrimination, in violation of women’s fundamental rights.

Since medical and technological advances have made abortion a simple and affordable procedure, the best abortion law would fully empower women to access a termination when they choose.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.

About ‘The Inspired Source’ Series

This series is part of our work to amplify the voices of aspiring writers that are underrepresented in the media and marginalised by society. Each piece examines a human rights issue by which the author or their community is affected. Where possible, authors outline a position on how we might begin to address the issue. Find out more about the series and how to send us a pitch on this page.