A right to internet access might sound trivial to some, but for many people access to the internet continues to provide a lifeline. Even after national Covid-19 restrictions have been lifted, many people remain dependant on the internet as a means of accessing medication, food, an education and a source of income.

In the last two years, the internet has been a platform on which people have flocked to demand and defend rights such as the right to health, the right to food , the right to education and the right to a family life.

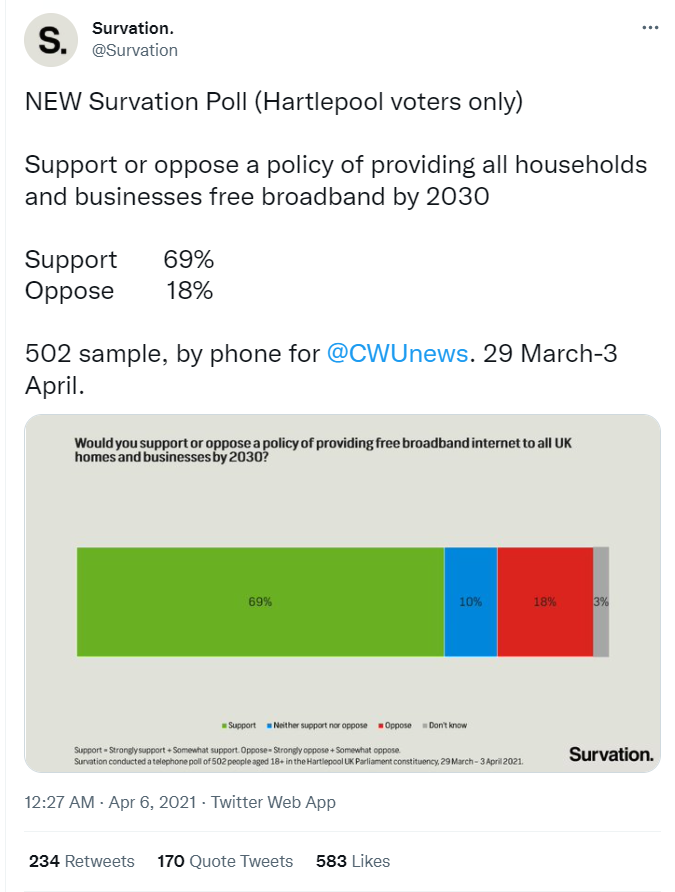

In 2019, ahead of the general election, then Leader of the Opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, was labelled a ‘crackpot-communist’ for calling to part-nationalise internet companies like BT. The Labour Party at the time unveiled plans to provide high-speed broadband fibre optic internet to every household and business in the UK by 2030.

The move was heavily criticised by internet providers like BT, while sceptical MPs derided it as unaffordable or claimed it would be illegal under EU law. Its reception among the general public, however, both at the time and subsequently, appeared much warmer.

Credit: Survation via Twitter

A lifeline for vulnerable people

In 2020, the UK entered its first Covid-19 national lockdown, with extensive restrictions, including isolation rules which were only lifted last month, after two years. However, as hospital cases now begin to rise again, many vulnerable people who have not stopped shielding will likely continue to self-isolate. For the most vulnerable in our communities, access to the internet can be a lifeline.

People who live away from their family or who continue to shield can be dependent on the internet as a tool to access basic human rights. Without it, for individuals during national lockdowns as well as those who continue to shield, the internet has become a crucial medium through which to invoke and uphold the right to health, the right to food and the right to a family life.

Credit: Andre Ouellet/Unsplash

When we say ‘internet dependent’, we are not talking about a right to play video games or watch Netflix. What we are talking about, often, is the most vulnerable people in our communities relying on access to the internet to access other vital resources. In the past two years, the idea of a right to internet access has appeared less trivial, as we have witnessed people in our communities struggle to access medication, to secure food for their families, as well as to provide children with an education at home.

Dr Julia Grace Patterson, the Founder and Chief Executive of Every Doctor, took to social media this week to remind us that we must continue to think of those most vulnerable in our communities who continue to shield:

COVID-19 case numbers are escalating very fast in the UK, it’s really really important that we consider the vulnerable people in our communities🚨

💙 Pls RT if you’re wearing masks 💙

— Dr Julia Grace Patterson💙 (@JujuliaGrace) March 15, 2022

The tweet received hundreds of responses from elderly people living alone, as well as families with vulnerable children, who said that they will continue to limit the extent to which they leave their homes.

MPs call for change

We spoke to Siobhain McDonagh MP, who has campaigned for children to have access to the internet, as well as a device at home, so they could access education during the pandemic. McDonagh told EachOther:

“When schools closed, children were asked to log in and learn from home. But those children on the wrong side of the digital divide – without the data and devices required – were unable to join their classmates.”

One of the main issues during the first national lockdown was that the government’s scheme to roll out laptops and IT equipment to schools took longer than anticipated, meaning children were unable to enjoy their right to an education, denied to them essentially because of their families’ economic standing. A child’s right to education was effectively dictated by their family’s ability to afford internet access, as the cost of living continued to rise. This issue was raised to McDonagh by a key worker:

“This problem was brought to my attention by Debbie, a local health visitor visiting homeless families. She was worried that the children she was visiting would fall even further behind, and I realised that this was a nationwide issue.”

Credit: Thomas Park/Unsplash

The digital divide

In March 2020, following discussions with the Government, the UK’s major internet service and mobile telephony providers agreed temporarily to remove data allowance caps on fixed line broadband services and added free extras to customers’ plans because of the pandemic. Mobile network operators removed data charges for accessing NHS websites offering information on COVID-19 and for using the NHS COVID-19 app. But internet companies did not waive caps on accessing education portals, pharmacies or supermarket sites.

McDonagh told us how she took action into her own hands to try and bring about change in her community. She stated:

“The Government’s rollout of laptops was far too slow. And so, I contacted all of the major tech companies and network providers to ask if they could help. Some were extremely generous, including Tesco Mobile, Three, O2, Ebay and Lycamobile – all who donated either devices, sim cards or funds. These were distributed through my local schools according to need.”

While the children in her local constituency benefitted from these donations, McDonagh realised that the digital divide was not confined to her community, and that there were thousands of people struggling to access basic needs across the UK. McDonagh told EachOther:

“Whilst my community rallied to support those children without the kit and connectivity required, this was clearly not an issue confined to my constituency. And so, in Parliament I lobbied the Department for Education, brought the issue to the attention of the Prime Minister, and introduced a Bill to campaign for all children entitled to free school meals to have access to the internet and an adequate device at home.”

Credit: Compare Fibre/Unsplash

Post-lockdown

The digital divide is the gap between people in society who have full access to digital technologies (such as the internet and computers) and those who do not. Concerns about the digital divide were voiced during the Covid-19 pandemic, because of the vital role that digital services have played in allowing people to access services which are intrinsic to their human rights.

However, the digital divide did not vanish when coronavirus restrictions began to lift across the UK. Still today, many are dependent on the internet to maintain an adequate standard of living. McDonagh insists that we must learn from the struggles we experienced during times of national lockdowns.

When schools closed, the move to remote learning highlighted the digital divide in our society.

But there are still pupils without the kit and connectivity required and for those still on the wrong side of the digital divide, every click widens the attainment gap.

Watch my Q! pic.twitter.com/QuUcb8Z2BK

— Siobhain McDonagh MP (@Siobhain_Mc) March 14, 2022

Earlier this week, McDonagh brought the digital divide to the attention of parliament once again. Speaking to EachOther, she expressed concerns that while many more children are back in schools, the digital divide itself has not vanished overnight:

“Whilst schools have reopened, so much is now online. Homework, research, catch up – every click widens the attainment gap for those who aren’t online. The days of pen and paper are long gone and the technological age we now live in is here to stay. The consequence for those children on the wrong side of the digital divide is that they are now even more disadvantaged than before.”

Credit: Alexander Dummer/Unsplash

Are there concerns about ‘trivialising’ rights?

Not everyone thinks that a right to internet would advance the cause of human rights. Barrister Sailesh Mehta told us that the right to internet would be too ‘encompassing’ and would raise questions about access to entertainment and pornography. Mehta stated:

“The right to education, which includes access to information, are important rights. However, a right to access to the internet is far too wide and encompasses other things that the internet is more used for – entertainment and pornography. This would have the effect of trivialising rights generally.”

Mehta also reminded us that, while access to the internet would be useful, there are other ‘basic’ things we need that have not been protected under the Human Rights Act (HRA). He added:

“About 60% of the world’s population already has access to the internet. This is growing by the year. It would be useful if everyone had internet access. It would make a difference to the lives of those who cannot afford access – but better access to water, food, unpolluted air and medicine would make a much greater difference and should take greater priority.”

Credit: Surface/Unsplash

‘You would find few who would support the move’

While Mehta states that there would be limited legal barriers, he claims that the economic barriers to realising such a right would be large and that it may be easier to subsidise the ‘few’ who cannot afford it.

Mehta told EachOther:

“There would be no legal barriers, but there would be economic barriers. The state would have to pay very large amounts of money to internet companies (upon whom the burden would be placed), or to set up a network, which would be even more costly.”

According to Mehta, not only may it be less of a economic strain to increase state benefits or reduce tax for those who cannot afford regular access to the internet, but it would be hard for people to support making internet access a legal right.

“Almost everyone in the UK has internet access. Those few that cannot afford it could receive a small increase in state benefit or tax discount – this would be a relatively modest amount and could be afforded by the state. It would not be beyond the wit of man and lawyers to make access to the internet a legal right – but you will find few who would support such a move!”

One of the main arguments for not making internet access a human right is the notion that it is not essential for survival, or not considered inherent to being human. For many though, the internet is a tool for survival that can be used to access food and medicine, to invoke the right to education, to earn a living and sometimes to offer the only contact they have with the outside world. There is an argument that in today’s post-pandemic society, people depend on the internet as a tool to access basic needs and that, as such, there is a case for considering what it would mean to make it a human right.