At the youth centre I go to, there is a memorial plaque for Rashan Charles: a young black man who died in 2017 after being chased by police into a nearby shop and restrained on the floor.

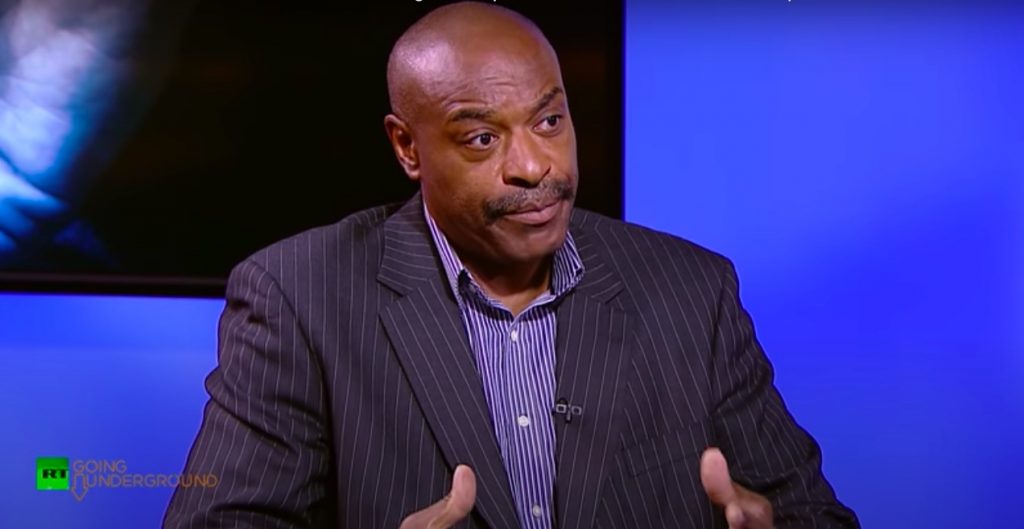

A post-mortem examination found that the 20-year-old went into cardiac arrest after choking on a package containing caffeine and paracetamol. The police, who claimed that they “sought to prevent [Rashan] from harming himself”, were cleared of misconduct, but found to have fallen short of “expected standards”. But retired chief inspector Rod Charles, who is Rashan’s great uncle, said CCTV evidence of the incident contradicts their claims and that the officers involved should face trial.

For me, the plaque symbolises how my community, like many others across the country, is overpoliced and underprotected.

The phrase ‘knife crime’ has dominated the headlines over the years. Through a regular stream of news reports, it has become a racially-coded way of referring to incidents of serious youth violence involving black people. There is rarely much context or explanation offered for the systemic or structural factors behind the rising count of “knife deaths”. Each tragedy is portrayed as a senseless act of violence, often motivated by petty rivalries.

Rod Charles, who is Rashan’s great uncle, said CCTV evidence contradicts officers’ claims. Credit: YouTube/Going Underground on RT

Black people 40 times more likely to be stopped and searched in UK

The Home Office has sought to address so-called “knife crime” by expanding use of stop and search. This has led to the targeting, profiling and mistreatment of black people, who in 2019 were more than 40 times more likely to be stopped without suspicion in the UK than their white peers. This is despite the fact that the majority of knife possession offenders under-25 in England and Wales were white only a couple of years earlier. In the year to March 2019, data shows that only 15% of stop and searches (58,251) in England and Wales under Section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act resulted in arrests – with the majority being for drugs, not weapons.

Stop and search is not only ineffective, its aims are flawed. It attempts to remove knives from the streets but not from people’s minds – failing to address the reasons behind why more young people are carrying weapons.

My community, like many others across the country, is overpoliced and underprotected

Tapiwa Cronin

We need to urgently recognise and address these real causes, which are likely to be made worse by the economic impact of the coronavirus. Poverty is expected to increase – with that already being a motivating factor for knife crime, it is coupled with educational challenges such as the lack of internet and mental health issues. Young people are more likely to find education difficult and disengaging and, during a time of personal financial troubles and a national economic crisis, unrewarding.

The preventive support that wasn’t reaching enough young people before the pandemic, such as mental health provisions and youth outreach, is struggling to be of use now. Many more young people can be expected to be vulnerable to knife crime.

Statistics show a sharp rise in the cases of youth violence as funding for schools and youth services have decreased. Between 2010 to 2018, the City of Westminster had a 91% decrease in funding and a 47% rise in youth violence as part of a wider £750 million cut to youth services in England.

A vigil for Rashan Charles in east London in 2017. Credit: Flickr/Alan Denney

We need to re-evaluate our approach to solving serious youth violence

The movement to defund the police reflects a frustration at the government for throwing money at an institution that is failing communities, while services they relied on are left depleted and disregarded. In January, the government announced the police would receive a £1.1billion funding boost for 2020/21 – the biggest increase “in a decade”. What we need is investment in youth services, education, schools, and we need this to reflect the value assigned to our lives and futures.

The movement to defund the police reflects a frustration at the government for throwing money at an institution that is failing communities

Tapiwa Cronin

We only have to look to Scotland to see evidence of the effectiveness of more holistic approaches. Glasgow was once known as the ‘murder capital’ of Europe – with a homicide rate of 2.7 people per 100,000 in 2012. But between 2013 and 2017, violent crime fell by 30% – a change credited to the country’s Violence Reduction Unit (VRU). As recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the unit took a “public health” approach to serious youth violence – treating it as a “disease” whose root causes it sought to analyse and develop solutions for.

Black Lives Matter is not a moment. With the pandemic set to increase economic hardship, we need to re-evaluate our approach to solving serious youth violence. Lasting change means investing in the heart of our communities.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.

About ‘The Inspired Source’ Series

This pilot series is part of our work to amplify the voices of aspiring writers that are underrepresented in the media and marginalised by society. Each piece examines a human rights issue the author or their community is affected by and preferably have a position on how we might begin to address it. This is a brand new series, so we are likely to adapt and refine it as things progress. Find out more about the series and how to send us a pitch on this page.