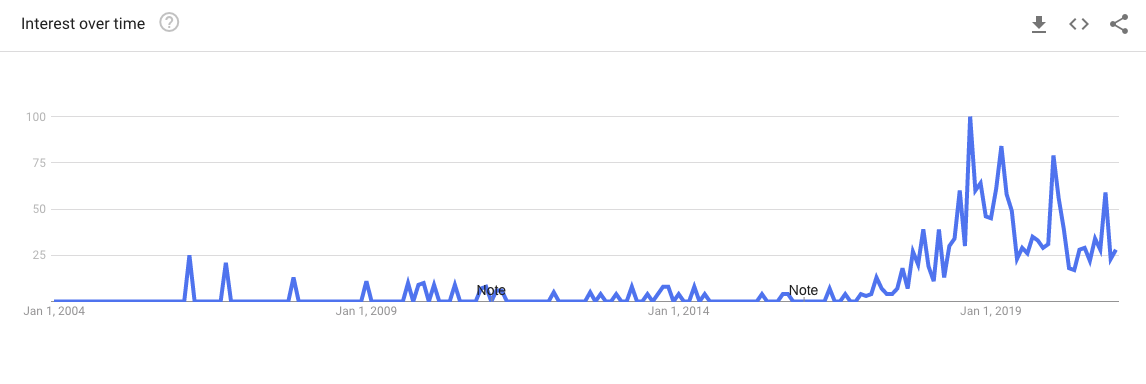

Before 2016, the term ‘period poverty’ was almost unheard of and Google searches for the phrase were pretty much non-existent. It wasn’t until a report came out from charity Freedom For Girls in March 2017 that the issue finally started leaking into the public consciousness – despite the fact academics say the problem has existed as long as poverty itself.

The report found that pupils in the UK were routinely missing school when they were unable to afford period products – or, in some cases, using toilet paper and sellotape or old socks as substitutes to simply get through the day. Touching on rights such as education, dignity and health, the question has always been one of human rights.

A lot has changed since 2017 – including a lot in the last few weeks alone. As of 1 January 2021, the so-called ‘tampon tax’ no longer applies, meaning that VAT will no longer be applied to period products. A fortnight later, a bill spearheaded by MSP Monica Lennon received Royal Assent, meaning local authorities and schools must now make period products available free of charge to all those who need them. The move follows commitments to make free products available in schools in Scotland, England, and Wales. However, despite the significant progress, both campaigners and academics say there is much more to be done.

A graph from Google Trends shows how searches have increased since 2004. (Image Credit: Google Trends / Screenshot)

While recent developments are undeniably steps in the right direction, many people who menstruate are still left without vital products – especially refugees, asylum seekers, and those who are homeless to name but a few. “I think the problem is that there isn’t country-wide policy or legislation about how people should be able to get access to essential products,” explains Gabby Edlin, the founder of Bloody Good Period, a charity which has provided products to asylum seekers since 2016.

“It all relies on people who can’t afford products knowing that there is a charity like ours, and the charity having the funds or products to provide them. And, generally, people who are seeking asylum or are refugees are forced into really unstable states. They might be moved around, they have very low funds. And, at the moment, it’s even worse, of course, because so many centres they might access regularly are closed.”

You are blamed for getting into the crappy situation, then somehow blamed for not managing money effectively. The blame is all on you and there is shame in asking for pads. I can’t even remember asking for pads when I needed them. I went without food instead.

Hollie

And, even if women are aware of the help available to them, stigma will often play a huge role in stopping them from accessing it. Speaking about stigma, Alison Briggs, who has written a paper on lived experiences of period poverty, said it can have a “hugely harmful effect on how people see themselves and how they believe others see them”. And, when it comes to periods, she says the stigma is a “double whammy”.

Firstly looking at food banks, which, as we revealed in 2017, have become a growing lifeline for those who need period products, “there’s a stigma attached and associated with food bank use”. “All sorts of moral judgements are made about people who have to depend on food aid in order to eat,” says Alison. Add to that the “prevailing taboos around periods” and how society has “determined that periods should stay hidden” and it becomes a “complex experience, [which is] humiliating and shameful, as well as the actual physical discomfort”.

A person puts period products into their bag. (Image Credit: Pexels)

It’s a narrative echoed by Hollie, who previously spoke to EachOther about her lived experiences with period poverty. After leaving home at 15, she had just £45 a week to live off. “Out of that I had to pay for a laundrette, electricity bills, and food. I was often short for pads and tampons, or I couldn’t afford to wash my bedding after a leak, so I would run my pills back to back if I couldn’t afford to have a period. This was common amongst the ladies I shared a house with. It was grim.

“You are blamed for getting into the crappy situation, then somehow blamed for not managing money effectively. The blame is all on you and there is shame in asking for pads. I can’t remember ever asking for pads when I needed them. I went without food instead.”

If you’re struggling to afford food, you’re going to be struggling to afford to heat your home. And you’re going to be struggling to afford other products as well.

Alison Briggs

For many, the reality is that period products will always get pushed to the bottom of the list. “You’ve got food poverty, you’ve got fuel poverty, you’ve got hygiene poverty – it intersects with all of those other dimensions,” explains Alison. “Essentially, if you’re struggling to afford food, you’re going to be struggling to afford to heat your home. And you’re going to be struggling to afford other products as well.

“But I think it’s important to focus on it as a distinct form of poverty, because of its corporal and gendered nature – the way it’s felt and the way it’s experienced. Food is the most elastic part of the household budget – you’ll find that mothers in particular will have employed various strategies to make their household food budget stretch, and indeed, the household budget.

There is a kind of hierarchy of ‘well I don’t need this, do I absolutely need to buy this month’s pack of tampons, or can I get away with not? And women are constantly having to make those really difficult decisions.”

Even without VAT, period products are still out of reach for many. (Image Credit: Wikimedia)

Again, these circumstances are echoed by many others who’ve spoken to EachOther. When Shauna Gaunlett gave birth to her son five years ago, she never expected to find herself unable to afford basic products. “I haemorrhaged because my stitches had burst,” she told EachOther. “I was in so much pain I couldn’t even get out of the house. I’d had my son on the seventh of the month, after we’d paid all our bills and then had extra bills to pay for since we changed electricity supplier. I had to rely on family and friends to buy maternity pads for me.”

For others, there can also be additional hurdles in place, thanks to societal attitudes to gender. Erin Campbell, a Member of Scottish Youth Parliament for Midlothian North and Musselburgh has been campaigning for free period products since 2019, as well as giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament Committee.

Initially, Erin was “shocked because it was so close to home,” and has since set up a ‘period packs’ initiative in their own school. “The reaction has been hugely positive, but it definitely has shown me that periods aren’t yet seen as normal and people are very quick to deny the experience of trans and non-binary people who also menstruate. This is a massive issue I want to help tackle.”

It has definitely shown me that periods aren’t yet seen as normal and people are very quick to deny the experience of trans and non binary people who also menstruate.

Erin Campbell, MSYP

Like everything else, it’s also an issue which has been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, with one study finding that almost 700,000 people had been driven into poverty. The team at Bloody Good Period also found they were giving out six times more products than before the crisis. And, while they put some of this down to people discovering who they were, it also indicates a growing need for access to essential products.

It’s clear that despite numerous steps forward over the past few years, there’s still a lot to be done. For Gabby, ultimately the answer lies in legislation. “I think the problem is that there isn’t countrywide legislation about how people should be able to get essential products,” she tells EachOther.

A protest by Bloody Good Period. (Image Credit: Jem Collins)

“That’s not to undermine the great work that we and other charities do, but they are, fundamentally, a bit rickety. Because they rely on public funding, they rely on capacity. But your period doesn’t care about someone else’s capacity and somebody else being able to get products.”

She points to their current campaign Bloody Free, which calls on the Government to follow Scotland’s lead on making period products free across the UK. “That basically demands free products for everybody who needs them. I think it needs to be a government funded initiative, I think it needs to be in legislation. I don’t think it can be something that we’ve already seen with the schools. With the schools provision, because it’s policy, the government was sort of chopping and changing with it.”

“Our real, legitimate ambition is that we don’t deliver period products in the next few years, because it’s taken care of by the Government,” she adds. “It can’t rely on a group of small charities, it just can’t. We need change not just charity. This isn’t just some frivolous thing that we’re trying to do; this is really about people’s self esteem and their bodily health as well.”

This isn’t just some frivolous thing that we’re trying to do; this is really about people’s self esteem and their bodily health as well.

Gabby Edlin, Bloody Good Period

When asked about how realistic she feels a timeline of three years is to see the end of her charity, Gabby says she “really does believe it’s possible”. “I never set it up with the intention of having a big, long-running charity: it was always a project that will be closed down once we’ve completed what we need to do. I think it’s doable – it’s just going to take the action of the public and putting pressure on the Government to care about this stuff – or act like they care.”

For Alison, solving period poverty only comes with tackling the root of the problem itself. “[Recent legislation] has been a step in the right direction,” she tells EachOther. “It addresses an immediate need, as do food banks. But what we need to ensure is that we address the root causes of food poverty, period poverty, hygiene poverty – all that. We need to campaign for a living wage, for an end to low-paid insecure jobs, and a properly functioning social security system that’s able to support people when they need it.

“It’s addressing those underlying issues, the root causes – and it tracks back to the same thing. But I think in the short term, having free products is a step forward and an important step forward. And that hasn’t happened in this country (England now provides free products in schools, but not more widely).” “I would definitely love to see the rest of the UK follow Scotland’s lead,” concludes Erin. “We’ve proven that making sure people have access to these products is not only a human rights issue, but an achievable one too.”