When 30-year-old Shauna Gauntlett gave birth to her son, it was supposed to be the happiest time of her life. However, following complications after the birth, she found herself in a situation she’d never thought she’d be in – she was unable to afford the sanitary pads she needed.

Speaking to RightsInfo she explained: “It was 18 months ago and I hemorrhaged because my stitches had burst. I was in so much pain I couldn’t even get out of the house. I’d had my son on the seventh of the month, after we’d paid all our bills, and then had extra bills to pay for since we changed electricity supplier. I had to rely on family and friends to buy maternity pads for me.”

Sadly though, Shauna’s experience of period poverty isn’t unique. A recent investigation by RightsInfo found that thousands of women were relying on food banks every month in order to cope with their monthly periods, while a report from Freedom4Girls discovered girls were also being forced to skip school for up to a week.

‘I Wouldn’t Ask For Pads – I Would Go Without Food Instead’

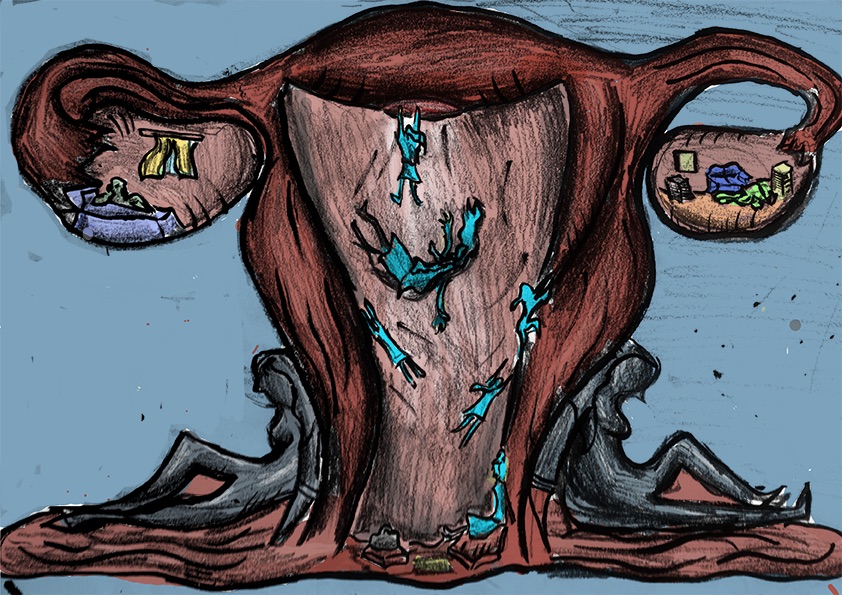

Women are often forced to choose between food and sanitary products. Image Credit: Skye Baker / RightsInfo

It’s an issue which touches on the very core of our human rights – dignity. It also affects other rights too – we all have a right to education, while a right to health is also a key human rights principle, enshrined in both the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Being able to hygienically and safely deal with your periods isn’t a luxury – it’s a basic expectation for every woman – and it certainly shouldn’t mean you end up missing school.

Hollie was just 13 when she first encountered period poverty. Living with an alcoholic step-dad there was limited cash for decent pads, so she went to the GP to sign herself up for the pill and saved up money from a paper round to pay for her own. Eventually, it all got too much and she left home at 15.

I would buy the cheapest pads I could get my hands on. They often leaked so I would avoid going anywhere.

“I was living off approximately £45 a week,” she told RightsInfo. “Out of that, I had to pay for a laundrette, electricity bills and food. I was often short for pads and tampons, or I couldn’t afford to wash my bedding after a leak, so I would run my pills back to back if I couldn’t afford to have a period. This was common amongst the ladies I shared a house with, it was grim.”

After she was accepted for a place at university things weren’t so bad – thanks to her student loan she could bulk buy products at the start of the term. However, when she graduated and gave birth to her child things worsened. “A suspected blood clot meant I could no longer use the pill, so I would buy the cheapest pads I could get my hands on. They often leaked, so I would avoid going anywhere.”

For Hollie though, the stigma surrounding period poverty was the worst thing. “You are blamed for getting into the crappy situation, then somehow blamed for not managing money effectively. The blame is all on you and there is shame in asking for pads. I can’t remember ever asking for pads when I needed them. I went without food instead.”

‘I Was So Humiliated. I Felt Like I Had Failed’

Image Credit: Skye Baker / RightsInfo

The shame of period poverty also resonated with Elle Rudd. Now 23 and a successful journalist, she found herself struggling after taking on an unpaid internship as part of her university course. “I would work from 8pm to 5am and then go to my unpaid internship five days a week,” she explained to RightsInfo.

To be crude, it came to the point where I used makeshift tampons and towels out of loo roll.

“I was paid in cash and it was a real struggle. I ended up being hospitalised with exhaustion twice after collapsing in public and lost two dress sizes while working. My daily diet consisted of just one bottle of Lucozade and one tray of £1 chips. To be rather crude and honest, it came to the point where I used makeshift tampons and towels out of loo roll. My card got declined when I was buying the cheapest tampons in the store.”

Calling her mum to ask for five pounds to help, she found herself bursting into tears. “I just felt so embarrassed,” she said. “I analysed everything I had bought that week that I didn’t *need* – a coffee, my bus fare when it was raining… It felt the most unfair. I was working my arse off and I couldn’t afford to take basic care of myself. I felt like everyone knew and was looking at me, judging me.

“When I look back on that horrific moment of not being able to care for the most base and involuntary act of being a woman, I should have just asked to borrow a quid from a colleague. But I was so humiliated. I felt like I had failed, that I was dirty and unclean and that people would judge me.”

As the campaign to end period poverty grows, with a #FreePeriods protest this week and more and more backing from MPs and political parties, for Elle, it’s all about finding a solution that keeps people’s dignity intact.

“It is utterly unforgivable that people are having to go through this. In what world is a period a luxury? Sure as hell didn’t feel luxurious as I did the walk of shame out of Asda with loo roll in my pants because I couldn’t afford to buy tampons.”