Spaces of human rights are constantly shifting – as we’ve seen with all the change in the world recently – and so we’ve launched a new mini series of explainers on current human rights issues to revisit some history and address new issues. (Part 1 looked at human rights themselves while part 2 asked what is the link between social justice and human rights? )

The third part of our human rights explainer series takes us through some of the ways the COVID-19 pandemic has affected our rights:

-

Right to life (Article 2)

-

Right to education (Article 26)

-

Freedom of assembly (Article 11)

-

Right to vote (Article 21)

-

Right to freedom of religion (Article 9)

-

Right not to be discriminated against (Article 14)

As United Nations secretary-general Antonio Guetteres recently said, the pandemic is “fast becoming a human rights crisis” and responses to the crisis must place “people and their rights…front and centre.” However, since February 2020, only three out of 400 COVID-19-related questions asked in the Prime Minister’s Questions were related to human rights. Parliament has been criticised for failing to pay sufficient attention to the issue.

In March 2020, the UK government fast-tracked the Coronavirus Act in four days. The Act contained emergency powers that enable public bodies to swiftly respond to the pandemic including powers to stop mass gatherings. The Act also puts individuals’ human rights at significant risk.

Here are a few, of many, case examples of how changing legislation in the UK has affected our human rights:

Right to life

Just as much as the Coronavirus Act has given the government extra powers, in the case of care homes in the UK, they perhaps didn’t do enough. By the end of May 2020, 16,000 residents of care and nursing homes had died, compared to 3,000 in Germany and 0 in Hong Kong.

Professor Martin Green, chief executive of the industry association Care England, blames the death on neglect from the very agency charged with looking after people – the Department of Health and Social Care [DHSC]. “In every crisis [the DHSC] go into overdrive about the NHS and forget social care.”

Credit: Unsplash/Dominik Lange

In late January 2020, The Care Providers Association asked the DHSC if specific action should be taken, and were told that there was nothing to advise. Finally, government guidance on 25 February came but was still relaxed; face masks did not need to be worn by staff and there were no blocks on visits.

By 27 March, the government had ordered 15,000 hospital beds to be emptied. Many patients were discharged without testing. Care homes, which lacked clinical expertise and medical equipment, were filled with possibly infected patients. With staffing absences and a lack of protective equipment, infected numbers quickly soared: 33 outbreaks in the first week of March quickly turned into 793 by the end of March. Those who died in care homes didn’t have their right to life protected.

EachOther’s founder and human rights barrister Adam Wagner’s thoughts about the pandemic’s effect on the right to life:

As I said at the beginning, the human rights framework gives no easy answers. But one thing is crucial to understand: the right to life (Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights) is at the heart of human rights. Without it, there are no other rights! /12

— Adam Wagner (@AdamWagner1) March 15, 2020

Right to education

Subsequent lockdowns have led to repeated school closures over the past year, and children and schools across the UK turned to their digital devices to gain access to education. However, many children did not have access to electronic devices and were restricted in their right to an education.

A lack of electronic equipment wasn’t the only issue. Getting online was also not something that everyone could do. Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that four percent of the UK’s estimated 27.8 million households did not have access to the internet in 2020, creating a ‘digital divide’.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that the government would do “everything possible” to support the move to home learning and that 560,000 devices were given out in 2020. However, in Tiverton Primary School in Haringey, where 50 percent of pupils do not have computers at home, only seven laptops were offered.

Credit: Unsplash/Ralston Smith

The pandemic revealed that online learning may become more likely in future, should another crisis occur, and at the same time revealed that such crises significantly impact the right to education. In addition, we’ve learned that in today’s world, the internet may be considered a necessity to uphold human rights.

Freedom of assembly

Lockdowns may have restricted our freedom of movement, but it hasn’t stopped the population’s need to campaign for social justice over the last year. Thousands showed up during multiple Black Lives Matter protests in June 2020, vigils for Sarah Everard in March and ‘Kill The Bill’ protests earlier this month.

However, the impact of the pandemic upon the right to protest remains unclear. The first restrictions imposed in 2020 contained exemptions that still allowed socially distanced protests to go ahead. When these exemptions were removed, nothing explicitly prohibiting protest gathering was added.

Credit: Unsplash/Max Letek

This left it to the courts to determine whether, or how, a protest was permitted. The courts said that whilst lockdown persisted, the police would determine whether a protest could go ahead. This ruling has been criticised for giving too much power to the police without parliamentary scrutiny.

This has led to a significantly unbalanced restriction upon the right to protest. While the Clapham Common vigil was restricted, outdoor gatherings for Armistice Day commemorations were not. There are fears that the Police, Crime and Sentencing Bill now being debated in parliament, which gives police further discretion to intervene in protests, will transfer current restrictive approaches to freedom of assembly and protest to a post-pandemic era, limiting the right to protest at all times.

The UK-based advocacy group, Liberty, took action against the government’s treatment of protest rights:

🚨BREAKING🚨

Liberty's lawyers, @BigBrotherWatch and 60 cross-party MPs & Peers have written to the Home Secretary:

YOUR TREATMENT OF PROTEST RIGHTS IS ILLEGAL

FIX IT NOWhttps://t.co/FLBgpNPDPw— Liberty (@libertyhq) March 20, 2021

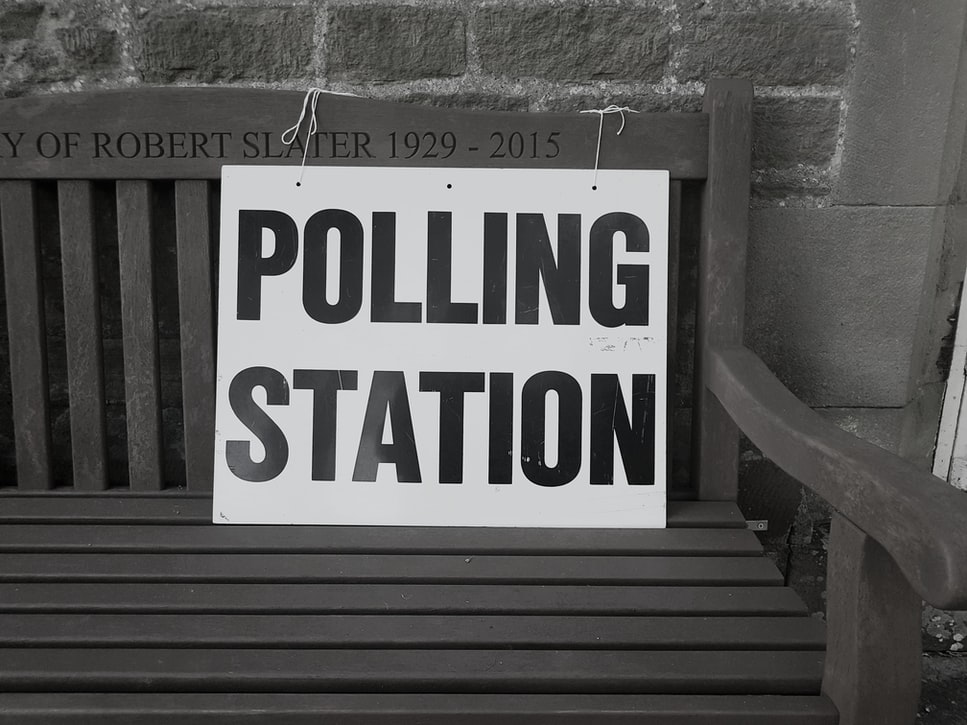

Right to vote

The May 2020 elections for the Scottish and Welsh parliaments, English local councils, local authority mayors, city mayors and police and crime commissioners are now due to take place in May 2021 after being delayed under the Coronavirus Act. This decision has also impacted the right to stand for election, as those running for election will be in office for three years instead of the usual four.

Due to the ongoing pandemic, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said the issue is being kept “under review.” Some commentators blame this delay on a failure to prepare and state that delaying the right to vote ‘puts democracy on hold.’

Credit: Unsplash/Steve Houghton-Burnett

Right to freedom of religion

Actions once seen as unquestionably communal such as worship, funeral ceremonies and religious festivals were restricted during lockdown. Churches, synagogues and temples were closed and communal worship was banned.

By the start of the second lockdown, England’s most senior faith leaders challenged the government’s decision to ban communal worship, citing freedom of religion enshrined in Magna Carta extending to public worship as the basis of their challenge against the government. They said that there was no scientific basis that linked places of worship with increasing illness rates.

Credit: Unsplash/Gabriella Clare Marino

Adding its voice, the Muslim Council of Britain, Britain’s largest Muslim umbrella organisation, described the government’s decision as “poor engagement with faith communities”. It stated that the new restrictions, which said places of worship must close for congregational worship but open for individual worship, was not practical.

Right not to be discriminated against

In March 2020, a person with a disability challenged the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for NHS clinicians about which patients should be admitted to hospital and referred to critical care. They argued that the guidance encouraged doctors to assess adults according to the Clinical Frailty Scale for Frailty Assessment (CFS), which only assesses physical difficulties. This discriminated against people with learning difficulties or mental health issues.

In response to this challenge, NICE changed its guidance in April 2020 to specifically state that the CFS should “not be used in young people, people with stable long-term disabilities, learning disabilities or autism. An individualised assessment is recommended in all cases where the CFS is not appropriate.”

Credit: Unsplash/Macau photo agency

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has unquestionably affected our human rights. They have made our access to its freedoms more vulnerable and increased the government’s power in order to reduce the spread of the virus.

The pandemic has also revealed significant structural weaknesses in the delivery of public services and the endangering heavy-handedness of security services. Often, these oversights lead to restrictions of multiple human rights; the neglect of social care reveals a negative effect of both the right to life and the right to protection from inhuman treatment.

As restrictions slowly lift, restrictions on our human rights may also begin to reduce. However, the effect of the pandemic on our human rights has served as an essential warning system — highlighting who is suffering most, and what can be done about it.

The COVID-19 pandemic has unquestionably affected our human rights. They have made our access to its freedoms more vulnerable and increased the government’s power in order to reduce the spread of the virus.

Part Four will discuss the future of our human rights. You can read Part One: The History of our Human Rights and Part Two: What is the link between Social Justice and Human Rights? here.

Follow Adam Wagner’s thread to access further analysis on how human rights are being affected by the pandemic:

I don't know where we will end. Nobody does. But as emergency laws are ratcheted up, and more extreme measures implemented, we need to critique the state response in a way which is both responsible and robust. People will say we are a nuisance. That's fine. That's democracy. /22

— Adam Wagner (@AdamWagner1) March 15, 2020