In the aftermath of a terrorist attack, when people are frightened and in need of reassurance, it’s common for governments to propose a tough response and new laws.

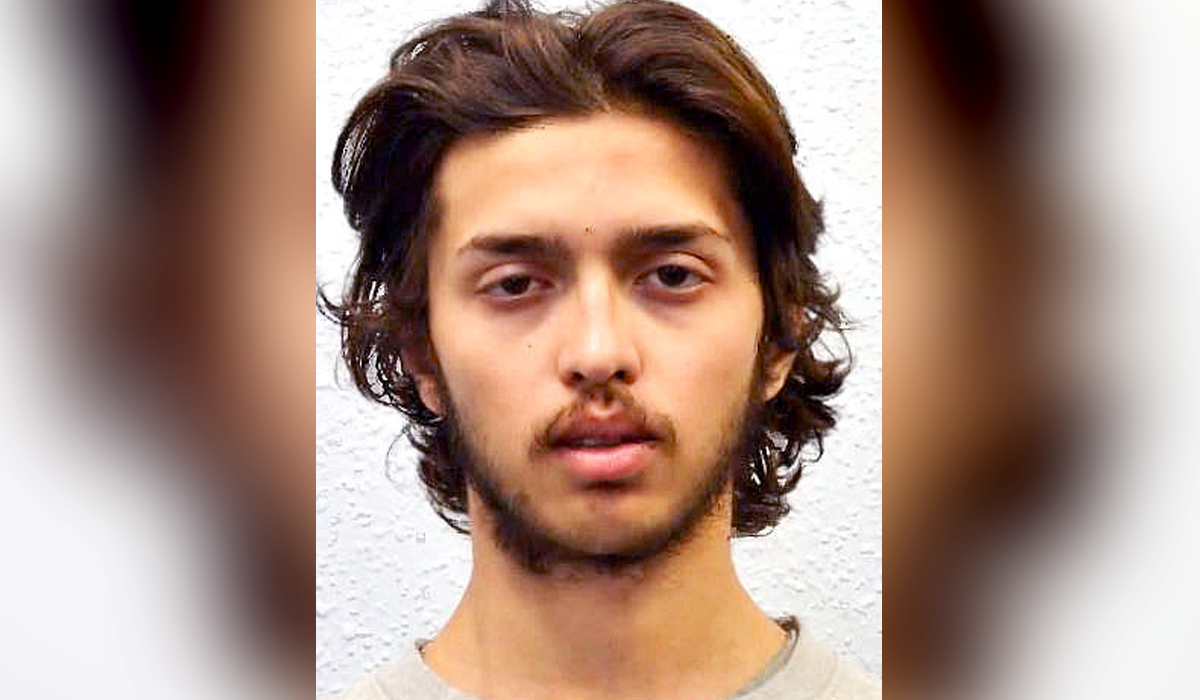

This is what recently happened in the UK after an attack in Streatham, London, by convicted terrorist Sudesh Amman. On Streatham High Road, Amman stabbed two people before being shot dead by police. He had been under police surveillance since his release from prison in January 2020 for terror offences.

Since the attack, the UK government said emergency legislation would be introduced to end the automatic early release from prison of terror offenders after they have served half of their sentence. Instead, they will be required to serve two-thirds of their sentence.

But there is a major issue with this proposal: it’s not at all clear that such a move would stop people committing these types of atrocities in the first place. And it also raises significant human rights concerns.

‘Rehabilitation rarely works’

This latest attack follows another recent incident in London where two Cambridge University graduates were stabbed to death and at least three other people were seriously wounded by convicted terrorist Usman Khan.

In the aftermath of the Streatham attack, Boris Johnson boldly stated that rehabilitation for convicted terrorists “rarely works”. So by his own admission, it seems the plan to increase the length of time terrorists will serve by 17 percent will also fail.

That said, there are no statistics in the UK to either back up or refute the prime minister’s claim. The former independent reviewer of terrorism legislation and now member of the House of Lords, Lord Anderson, recently asked the Ministry of Justice for figures on how many convicted terrorists commit further terror offences when released from prison. It remains to be seen what the answer is.

Credit: Pixabay.

There is some evidence from elsewhere that deradicalisation programmes in prisons can work to some extent. But care is needed when comparing different state programmes and different groups labelled as terrorist.

Evidence from Sri Lanka, for example, looks at deradicalisation with a group of Tamil Tigers – who sought to secure an independent state of Tamil Eelam. In this instance, the group had a distinct goal that could be identified and engaged with. Likewise, the conflict in Northern Ireland came to an end with the peace settlement of the Good Friday Agreement. It was this, rather than any deradicalisation programme that ended the violence there.

My research, however, has shown that a key factor to the endless “war on terror” is the idea that Islamic extremist terrorism has no feasible goal – so there is nothing to negotiate with.

This raises the question of whether rehabilitation programmes would work on Islamic extremist terrorists or the ever increasing numbers of far-right extremists in UK prisons.

Retroactive punishment?

The proposals to change terrorist sentences also raise enormous human rights concerns. Article 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights prohibits retrospective criminal laws. This means a person cannot be punished for something that was not a crime at the time they committed an act and that if the act was already criminalised, they cannot be made to suffer a harsher sentence.

So it may be the government’s proposals to change the automatic release dates will be found by the courts to amount to retrospective punishment. In some cases people will have pleaded guilty on the basis they would be released at the halfway point of their sentences.

Retrospective criminal punishment was a notorious tool used by Nazi Germany to target their enemies. The stigma attached to retrospective criminal laws is so strong, the European Convention on Human Rights does not even allow states to use this during a state of emergency. So it’s inevitable that a challenge to these laws will end up before the courts – and may set the stage for a future clash between the UK government and the European Court of Human Rights.

Restrictions and relocation

The UK already has some of the most robust counter-terrorist laws in the world. Indeed, the home secretary, Priti Patel, has the power to place an array of restrictions on a person she suspects is involved in terrorism-related activity.

Known as TPIM (Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures), this can include electronic tagging, periodic reporting to a police station, house arrest for certain periods of the day, excluding a person from certain areas and restricting their electronic communications. In certain instances, people can even be subjected to forced relocation orders, requiring them to move away from their home address.

Police had been following Sudesh Amman closely since his release, as they believed he posed a high risk of committing an attack. But the home secretary did not make him subject to a TPIM. This seems an oversight given his risk of re-offending was thought to be so high that police were monitoring him closely in the lead up to the attack. This also raises further questions: when are TPIMs being used and how often?

Eroding democracy

Two attacks by recently released offenders would suggest terrorists re-offending is a genuine issue. But without the statistics to show how many convicted terrorists commit further terror offences when released from prison, it’s hard to know the scale of the problem. And going by the available evidence, it’s difficult to say whether such changes in law would make us safer.

Yet with every new attack and the new counter-terrorist laws that follow, what is certain is that human rights are being eroded further still. This is not to take away from the suffering of victims, but governments must think very carefully before sacrificing those very human rights that give the state its identity and democracy.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.