Misogyny – the hatred of, aversion to, or prejudice against women – is becoming ever more common within our society, yet little is being done to tackle it effectively.

With 86% of women in the UK aged 18-24 experiencing sexual harassment, it’s clear to see that misogyny is rife. But despite its prevalence, misogyny is still not classified as a hate crime. Hate crimes are defined as crimes committed against an individual because they are part of or perceived to be part of a certain demographic. Currently, protected characteristics covered by hate crime law include race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, and transgender identity, but not sex and gender.

The omission of these categories remains glaringly obvious after calls to add them to the list of protected characteristics covered by hate crime law were denied in the wake of Sarah Everard’s murder, which re-ignited the conversation around women’s safety and gender-based violence.

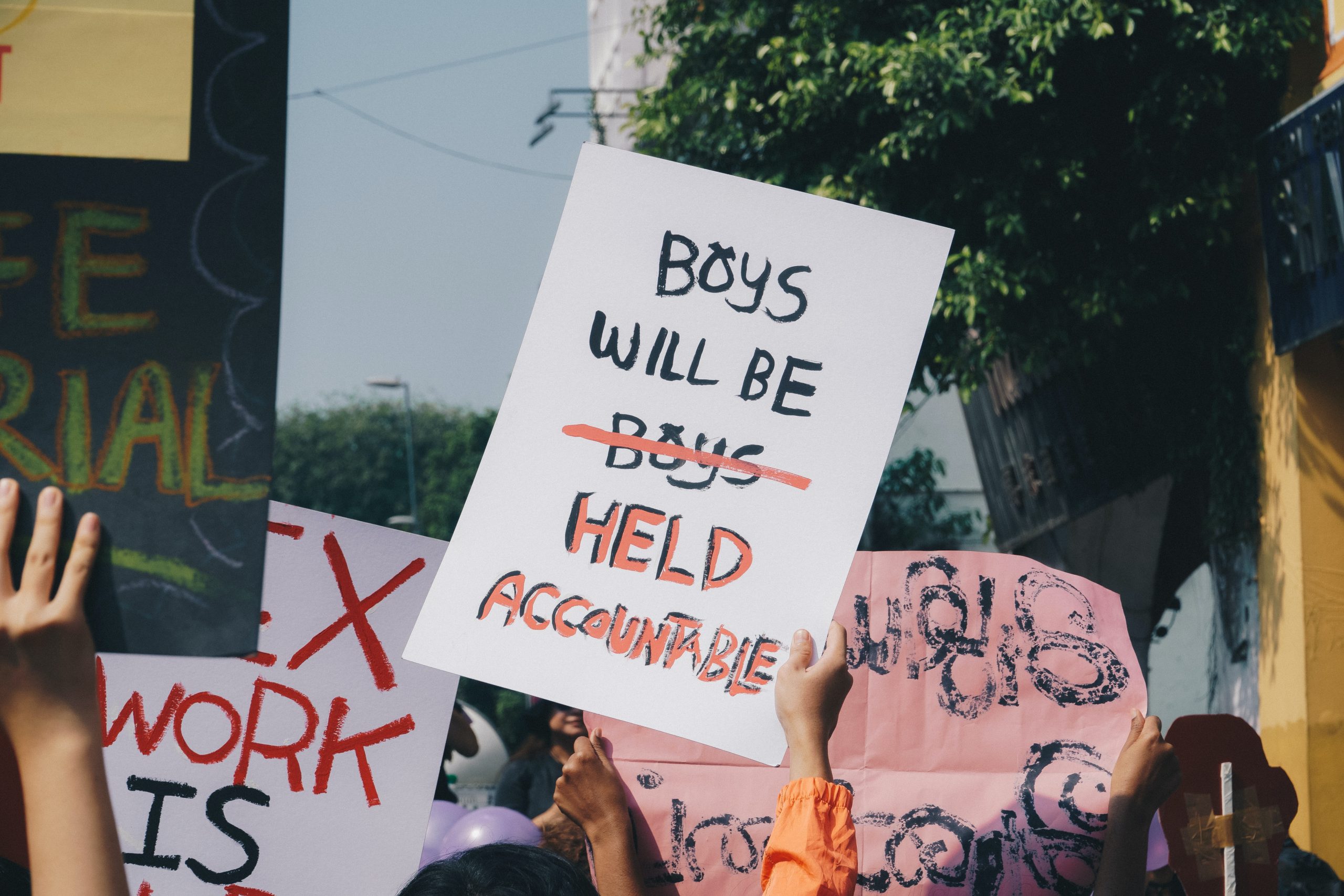

Credit: Kai Pilger / Unsplash

It’s wishful thinking to believe that misogyny neatly stays within the confines of being catcalled in the street or being groped on the bus or tram. Misogyny infiltrates every part of our society and touches the lives of women everywhere.

Even the Metropolitan Police, the service responsible for enforcing justice in the capital, is facing scrutiny for what critics like Sue Fish (former Nottinghamshire police chief) and MP Dianne Abbott describe as a culture of institutionalised misogyny. These concerns come after the prosecution of multiple officers for rape, reports of racist and sexist online chats between officers, and the prosecution of two officers for taking and sharing pictures of the bodies of murder victims Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry “for their own amusement”.

Women are often unsafe at the hands of the police, but what is disturbing is that, for many young women today, misogyny is also entrenched in schools and universities. Following the death of Sarah Everard, more than 54,000 testimonies of abuse and harassment in educational institutions filled the website of the anti-rape movement Everyone’s Invited. This movement later inspired a BBC documentary, featuring Love Island’s Zara McDermott, who discussed her experiences whilst interviewing girls up and down the country.

Credit: Markus Spiske / Unsplash

During my own years in high school, it was not uncommon to face misogynistic comments. In the midst of a conversation about female astronauts going to Mars, a boy sardonically remarked, “We want to build an actual establishment up there, not a kitchen”. This sentiment was easy to find among many boys who would tell me and a number of my female peers, who also happened to be women of colour, that there was “no point” in getting an education, given that we would “end up at home with a husband and kids”.

It was always clear that, for many boys, the intent behind these comments was to exercise a sense of control and entitlement over girls in the class by making us feel intellectually inferior and guilty for daring to participate in our education. But the underlying racism hidden in a lot of these remarks often went unnoticed.

Having a South Asian heritage means that I often have to contend with a lot of stereotypes. Frankly, it’s exhausting. I have to reckon with people’s prejudices in regard to my gender as well as my ethnicity. However, I have noticed disparities in the ways in which racism and misogyny are handled – both within a school environment and more generally in society. Whilst it’s true that allegations of racism can be dismissed or handled incorrectly, they are typically treated with more seriousness than allegations of misogyny.

Credit: Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona / Unsplash

When girls speak up about mistreatment, they are often told that they are being too emotional or sensitive. It’s ingrained within the culture too. Girls, from a young age, are told that if they are teased or taunted by boys in the playground, it’s because “he fancies you”. Those influencing and enforcing our laws often downplay the seriousness of misogyny and dismiss the dire need to tackle it.

In 2018, Sara Thornton, the then chair of the National Police Chiefs’ Council, said that the focus should be on “core policing” due to “overstretched” police resources, rather than tackling misogyny. Dame Cressida Dick, who stepped down as commissioner of the Metropolitan Police yesterday, supported Thornton by saying: “In terms of misogyny, we have hate crime legislation currently. We have aggravating factors, racially, or race hate. We have specific statutes and offences, we don’t have those in relation to gender-related crime or misogyny and, in my view, we should be focusing on the things that the public tell me they care most about.”

This idea that misogyny is not as important as racism trivialises the issue, and further plays into the mindset that women are troublemakers for taking a stand. The reality is that both issues desperately need to be tackled effectively because they are frequently interlinked. Making misogyny a hate crime would put the much-needed and long overdue support of the law behind women.

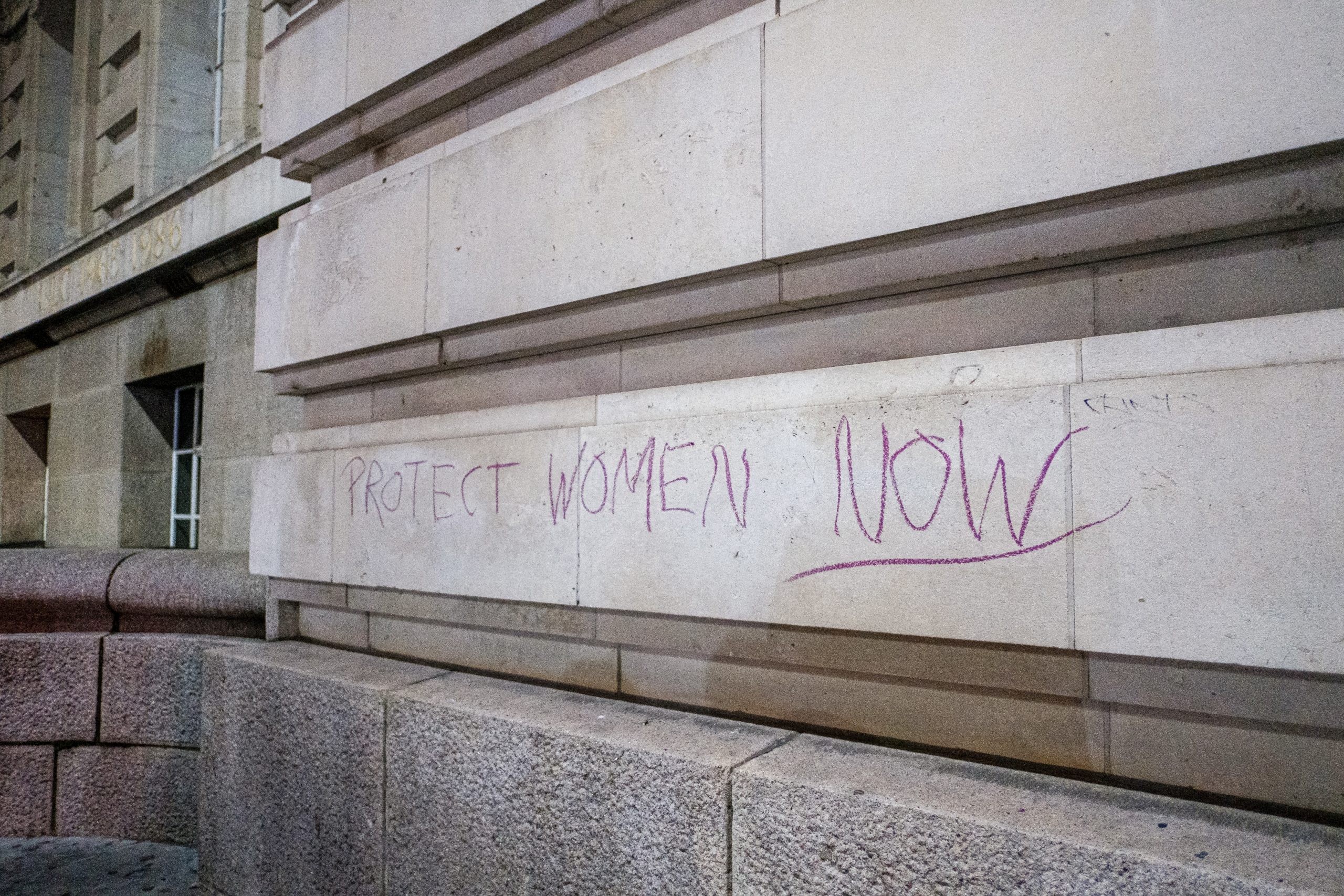

Credit: Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona / Unsplash

Article 14 of the Human Rights Act (HRA) sets out the right to freedom from discrimination. Just as with issues like racism or ableism, misogyny is fundamentally born out of discrimination (in this case based on gender or sex) and there is no valid reason why it should be less deserving of criminalisation.

Misogyny not only facilitates foul and sexist language but also makes for gender-based violence in the long term. Such violence has claimed the lives of countless women over the years. Femicide Census, an organisation providing ‘comprehensive information about women killed in the UK’, reports that a woman is, on average, killed by a man every three days.

Whilst an endless number of cases never make the news, some recent, high-profile incidents include victims like Sabina Nessa, sisters Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman, Julia James and Ashling Murphy. Article 2 of the HRA pertains to the right to life. The threat of gender-based violence infringes on it. That is exactly why misogyny, its root cause, desperately needs to be made a hate crime.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.

About ‘The Inspired Source’ Series

This series is part of our work to amplify the voices of aspiring writers that are underrepresented in the media and marginalised by society. Each piece examines a human rights issue by which the author or their community is affected. Where possible, authors outline a position on how we might begin to address the issue. Find out more about the series and how to send us a pitch on this page.