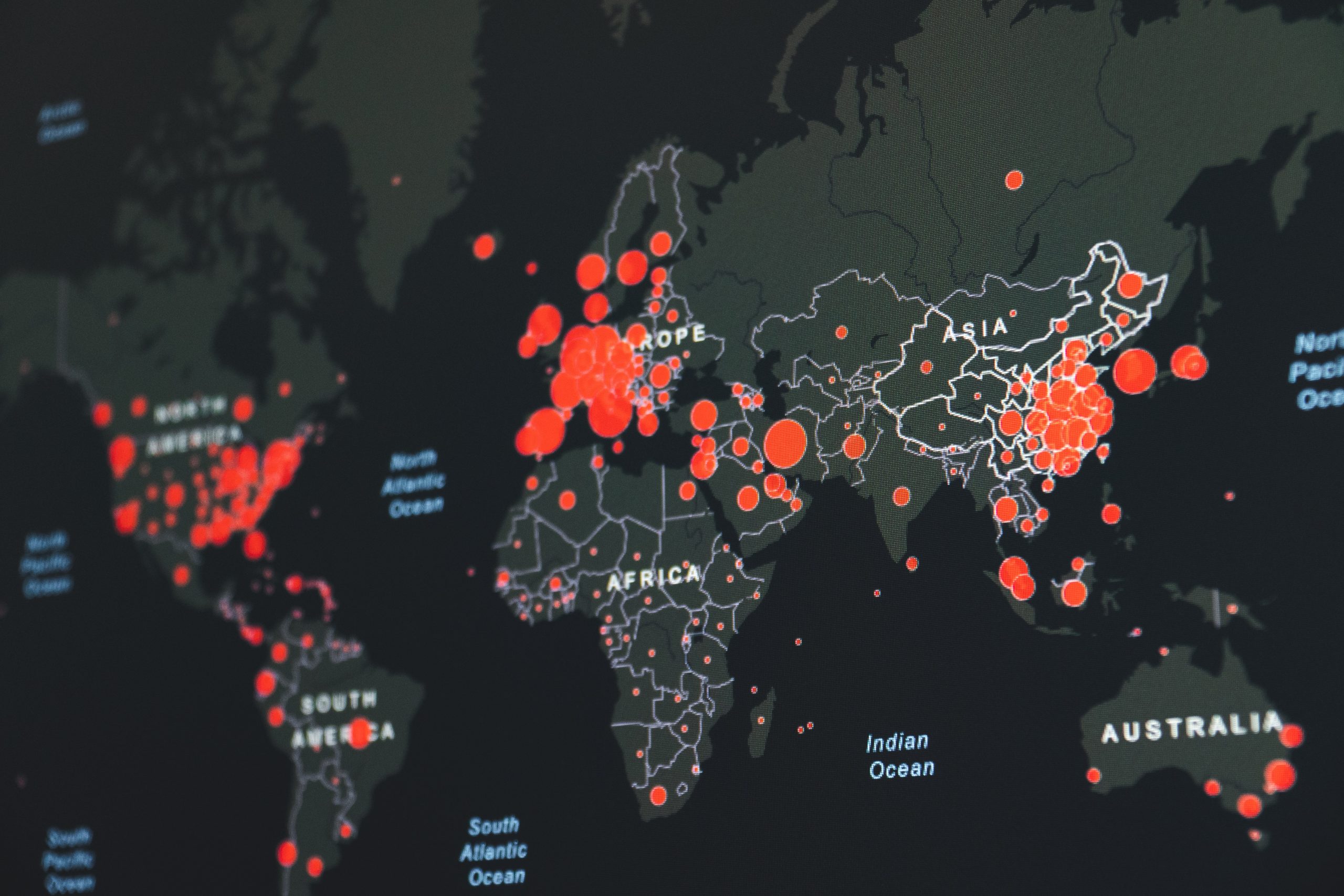

Thanks to the 24/7 news cycle, we are all aware of the ever-present threat of emergencies, whether natural or manmade. But, as the coronavirus pandemic continues, inequalities in emergency planning have been exposed.

Disaster or emergency preparedness refers to the measures undertaken by governments, organisations, individuals or communities to improve response to and cope with the aftermath of a disaster.

While other countries live with the constant threat of tornados, tidal waves or hurricanes, flooding is the natural hazard which most affects the UK. Nor is the UK a stranger to manmade emergencies, such as terrorist attacks or chemical, radiological, biological or nuclear incidents.

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, the government has been criticised for failing to protect all groups equally, with disproportionately high Covid-related deaths devastating disabled people and minority ethnic groups.

To find out whether the UK is really preparing for emergencies with equality in mind, we looked deeper into the issue.

What Does Emergency Preparedness Look Like In The UK?

Credit: Chris Gallagher / Unsplash

In the UK, the Cabinet Office regularly produces documents on current threats. The publicly available list is called the National Risk Register, covering environmental hazards, societal risks, major accidents, human and animal health, risks overseas and malicious attacks.

The government analyses these risks to establish how to respond and to categorise the threat level they pose. EachOther spoke to a former senior leader within UK counter terrorism policing to gain an insight. The source has been instrumental in the development of national counter terrorism doctrine and policy at both tactical and strategic levels and requested not to be named.

“The Cabinet Office constantly scans and reviews the globe for legitimate and credible threats to the UK,” they said. “For example, a marauding terrorist attack (MTA): they constantly scan the globe looking at attacks that may fall into the bracket ‘MTA’ or ‘active shooter’ to map out what an attack may look like in the UK, if it were to happen here.”

The source continued: “They ask: what sort of weapons may be used and what sort of ammunition? How many rounds may they carry? What sort of injuries based on that ammunition are likely? How many people will die immediately? How many people will bleed out in 30 minutes? How many people will bleed out in an hour, two hours? Will there be fire? Will there be smoke? Will that be purposely caused or will it be a consequence of the attack?”

Credit: Artiom Vallat / Unsplash

Identifying the risks is only the first step. The government then carefully assesses the likelihood of each threat and prioritises how to prepare for it.

“It’s a bit like any other risk approach, which is that you look at the likelihood of something happening and then you look at the potential impact,” said Lord Toby Harris, chair of the National Preparedness Commission, established in 2020 to consider and promote improved emergency preparedness. “Some of these are very difficult to quantify, what the likelihood is, the impact also is very difficult.”

He added: “There’s no precision: you’re investing money to try and prevent or mitigate something which may not happen or may not happen in the immediate future, but might happen in the future or might happen tomorrow. It’s often not visible. And if you never need it, it looks like wasted money.”

Due to a long history of managing threats to national security, the UK’s disaster preparedness is among the best in the world.

“I believe I am uniquely placed to say that the UK does have the best disaster preparedness in the world,” said the anonymous source. “The police, the fire, the ambulance, and UK special forces, who all work together domestically, are all trained, equipped and resourced, to deal with the same incident.”

What Did The Pandemic Expose?

The Covid-19 pandemic has hit communities hard across the UK but shortfalls in preparedness meant some groups faced the brunt of it, particularly those from minority ethnic groups and disabled people.

Disabled people have, so far, made up 60% of Covid-related deaths in the UK and deaths among minority ethnic groups have been disproportionately high. Despite the higher mortality rates in these groups, messaging has not been adapted to include them.

Throughout the pandemic, press briefings and informational materials were distributed without sign language interpreters, closed captions or image descriptions. One disabled woman brought a judicial review against the Department of Health and Social Care after receiving inaccessible communications from the government, over which the department later backed down.

“We need to make sure that public broadcasts are accessible,” said Lorraine Wapling, an independent researcher and consultant on inclusive international development. “What about visually impaired people and physically impaired people who need more assistance or people who are using carers to carry out basic activities of daily living, where are they in the briefing? It’s not like people don’t know that these things are needed.”

Wapling added: “I think basic principles still need to be talked about: this is a human rights issue. It’s about making sure people realise that disabled people have equal rights to access information services.”

Is Emergency Preparedness Equal For All?

Credit: Mufid Majnun / Unsplash

Due to the overwhelming number of potential emergencies, devising plans that encompass all possible eventualities is a monumental task, which the National Preparedness Commission works on breaking down.

“Often the mitigations done at government and national level are not granular enough to look at what you would do in terms of a local plan,” said Lord Harris. “For example, floods: how do we deal with disabled people? How do we deal with people who have got limited ability, older people and so on?”

Typically, such preparations are handled on a local level by local resilience forums (LRFs), which identify potential risks and produce emergency plans to prevent or mitigate the impact of incidents in their local communities. LRFs became a statutory requirement following the Civil Contingencies Act 2004.

However, some LRFs have more experience in managing emergencies than others. Harris says “they vary quite widely” and although many are well-developed, others have a more “ad hoc” approach to preparedness.

Credit: Billy Wilson / Flickr

Emergency preparedness takes many forms, varying from preparing individual buildings to ensuring emergency services are prepared to handle any situation. Making these preparations effective for everybody is a substantial task.

The government’s risk register identifies the likelihood of risks and the potential fallout of their occurrence. Some of the government’s response and prevention tactics are publicly available but preparedness also relies on individual organisations and businesses.

“Protective security includes how to protect or target-harden people, places, buildings and events,” said our anonymous source. “This could involve determining what sort of glass you use in windows or which bollards you use when considering hostile vehicle mitigation within your protective security plan. It can also include upskilling those people who work inside the venues to make sure that they are better aware of what is going on around them, and what to do if something was to happen.”

There is still a lot of work to be done on making responses inclusive

He continued: “The bigger questions are: is it the role of the police, fire and ambulance services alone to resolve a manmade crisis? My contention would be it’s not – it’s the responsibility of us all to resolve that problem.”

When it comes to protecting vulnerable groups in emergencies, such as disabled people, places or areas which are deemed to be under particular threat are relied upon to have pre-prepared plans to ensure everyone is taken care of equally.

“There’s no getting away from it, protective security and preparedness cost money,” said our anonymous source. “If you’ve got a world with a contracting economy, the last thing you want to be doing is spend money on ‘what-ifs’. Everyone deserves to be looked after – disabled or otherwise. I worry that sometimes cost plays a role in determining what should be done to keep everyone safe.”

One of the major difficulties of emergency preparedness is its financial implications. With the prospect of re-election always looming, it can be difficult for politicians to justify injecting funds into preparing for situations that may never happen.

Credit: Martin Sanchez / Unsplash

“The focus on getting re-elected is not necessarily the same as preparing for these disasters,” agreed Lord Harris. “There isn’t some shiny new thing to open, there isn’t some immediate benefit for people now. However, the government’s first task is to keep people safe.”

Wapling believes that to make emergency preparedness more equal and inclusive, there needs to be a significant shift in attitudes and improved awareness of disability.

“There’s a sense that it’s very individual impairment-focused, so a lot of disaster response is still geared towards helping people who’ve been injured or disabled during a crisis,” she explained. “That’s very much about providing medical support and stuff like that, which is essential but that’s not an inclusive disaster response.”

She continued: “There is still a lot of work to be done on making responses inclusive, which include making sure whatever you’re delivering is physically accessible, but also to do with information and relevance. There’s still a lot of work to be done on including disabled people in the decisions that are made around what gets delivered, who gets resources.”

While disabled people are protected from discrimination under the Equality Act and the Human Rights Act, there is no specific legislation outlining how to approach inclusive emergency planning and protect vulnerable people from discrimination when it comes to the country’s preparedness for disasters.

Harris said: “What you would hope is that any mitigation plan, any disaster plan, would be taking that into account. There isn’t anything specific, other than general disability legislation, that says you shall do this. Indeed, there is very little which says what you should be doing about any of these things.”