People say that a picture paints a thousand words, but even after the #MeToo movement surged to global prominence, it seems there is still an air of silence surrounding image-based sexual violence. Being a victim of image-based sexual abuse myself, I have begun to wonder if we, as a society, truly understand its prevalence.

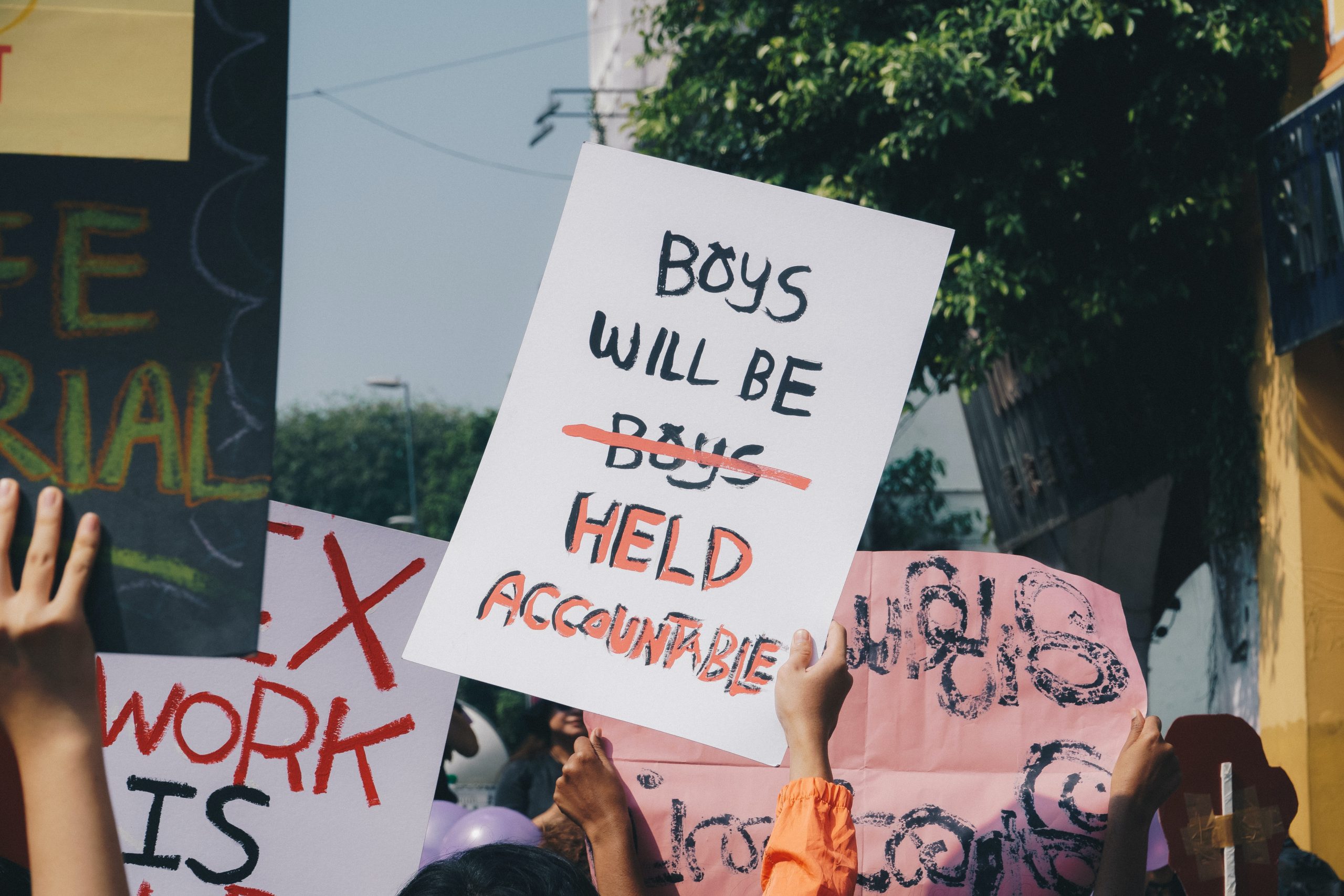

In 2017, #MeToo began trending on social media platforms, with the movement itself having begun in 2006, started by survivor and activist Tarana Burke. Through the hashtag ‘#MeToo’, people – primarily women – stood together sharing their experiences of sexual assault and harassment. Consequently, the world was forced to confront the sheer magnitude of the problem.

In terms of human rights, sexual violence is a violation of one’s right to a private life, as expressed in Article 8 of the Human Rights Act (HRA). But, as it disproportionately, although not exclusively, affects women, it also impacts the right enshrined in HRA Article 14, which outlaws discrimination.

Credit: Michelle Ding / Unsplash

While organisations like the World Health Organisation have published reports highlighting sexual violence as a serious public health and human rights issue, it seems like the #MeToo hashtag did something else equally powerful. The hashtag worked to humanise those who have experienced such violence. Survivors were able to use social media as a channel to challenge directly the silence that surrounds sexual violence. I would love to say that the story ends there. Sexual violence, though, still impacts the lives of many, with more than 80% of young women in the UK having experienced sexual harassment. We have also seen a rise in sexual violence of a digital nature.

Just as sexual violence pervades our society, the digital sphere is not free from it either. There, we have seen the rise of a distinct kind of sexual violence: image-based sexual abuse. According to data attained by the BBC from a range of police forces across the UK, between 2015 and 2018 there was a 78% rise in cases of image-based sexual abuse. This type of sexual abuse was formerly referred to as ‘revenge porn’, a term that has since been criticised for suggesting that such acts are simply about revenge. Unlike the term ‘revenge porn’, the term ‘image-based sexual abuse’ refers to a wide range of harms centred on ‘the non-consensual creation and/or distribution of private sexual images’.

Image-based sexual abuse is far more than just the sharing of private sexual images, motivated by revenge. As highlighted by Birmingham Law School, the term also covers:

- the non-consensual creation of sexual imagery through upskirting, forms of voyeurism and sextortion;

- the recording of sexual assaults; or

- instances where perpetrators threaten to share images.

Prior to becoming a victim of image-based sexual abuse, I, like many others, had no idea what it was, let alone the range of acts to which it refers.

Credit: Chad Madden / Unsplash

The day I found out that I was a victim of such a crime, a bubble burst. I felt violated. Confused. Used. Not only did this person commit an act of image-based sexual abuse against me, but they also took away my privacy. As I struggled to come to terms with my experience, questions have since rushed around my mind. Why didn’t I know that this was such a serious issue? Is wider society even aware of the gravity of the problem?

I believe that our awareness may be clouded by a lack of education on image-based sexual abuse, coupled with a wider normalisation of sexual violence. Unfortunately, what happened to me was not my first experience of sexual violence. I was first sexually harassed when I was 15 and I was first sexually assaulted at the age of 19. Now, aged 22, I realise that for most of my teen and early adult years, I made sense of these experiences by blaming my own visibility, trivialising instances that caused me great harm. I am not alone in doing so.

As a society, we tend dismissively to blame the victim. For example, a survey carried out for The Independent found that 55% of male respondents subscribed to the view that wearing revealing clothes makes someone more likely to experience unwanted sexual advances. Additionally, it found that 41% of female respondents held the same view. But why do people feed and buy into such narratives? And, importantly, how may this be affecting our awareness of image-based sexual abuse?

Credit: Markus Spiske / Unsplash

According to David B Feldman, a professor of counselling psychology at Santa Clara University, “our tendency to blame the victim may originate, paradoxically, in a deep need to believe that the world is a good and just place”. Like others, I wanted and still want to believe that the world is good and just, and though I am naturally quite sceptical, I still cling onto this hope by a thread. But this desire, coupled with an ignorance towards matters of sexual violence, seems to create a culture of silence within our society. This is reflected in the fact that, as estimated by the Office for National Statistics, only around 15% of those who experience sexual violence report it to the police. In looking at the issue of image-based sexual violence, victim-blaming narratives might limit the extent to which we are aware of the scale and severity of the issue.

In my experience, I was initially reluctant to speak about what had happened to me, as I feared that people would judge me or blame me for what happened. Honestly, I blamed myself. I didn’t want to believe that something so bad could happen without me being at fault. But it wasn’t my fault, and it is never the victim’s fault. However, our tendency to direct blame onto the victim affects our willingness to hear and accept victims’ experiences. This may simultaneously curtail the extent to which people speak up when acts of image-based abuse do take place.

Today, I, like many others, have chosen to speak up, despite my fears. I needed to give myself a voice. I hope that, in doing so, I motivate people to acknowledge and educate themselves about the harm that image-based sexual abuse can cause.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.

About ‘The Inspired Source’ Series

This series is part of our work to amplify the voices of aspiring writers that are underrepresented in the media and marginalised by society. Each piece examines a human rights issue by which the author or their community is affected. Where possible, authors outline a position on how we might begin to address the issue. Find out more about the series and how to send us a pitch on this page.