When the Human Rights Act came into force 17 years ago it was hard to imagine the hostility it would face.

In the early 2000s there was a hope that it would empower the users of public services and become embedded into society. Yet by the time the Act turned 14, plans were already released for its repeal and politicians spoke openly of the UK withdrawing from the Human Rights Convention. Where do we stand now it’s turned 17?

We Must Look at the Root of the Arguments

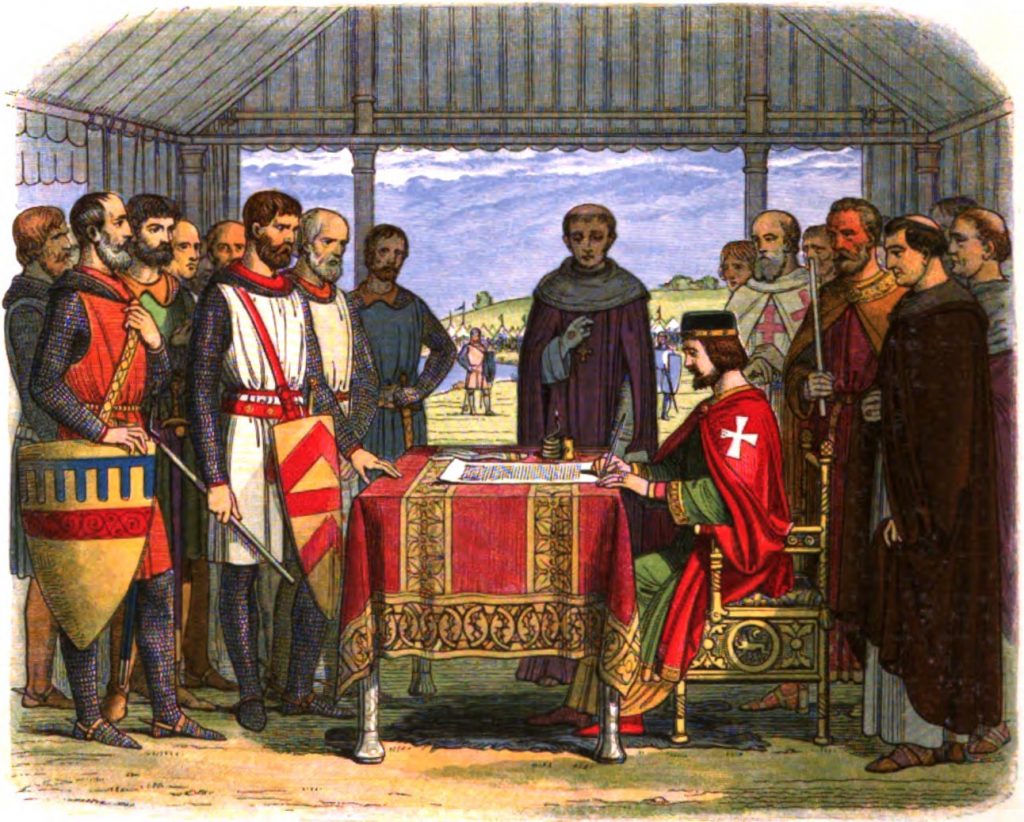

A later recreation of King John signing Magna Carta. Image Credit: Public Domain / Wikimedia

A later recreation of King John signing Magna Carta. Image Credit: Public Domain / Wikimedia

To understand how this happened it is important to look at the why the arguments against the Human Rights Act (HRA) have such force. Constitutional traditions and instruments such as Magna Carta afforded some limited protection of rights prior to the HRA.

This made it easy for opponents to claim that it was alien to British tradiations, even though the Constitution is constantly evolving

Classic writers on the British Constitution in eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such as Jeremy Bentham and William Burke, were heavily sceptical of the notion of abstract rights, seeing them as the antithesis of common law and parliamentary democracy. This made it easy for the HRA’s opponents to claim that it was unnecessary or alien to British constitutional traditions, even though the UK’s Constitution is constantly evolving.

Attacks Which Miss the Point

Some critics claim it has given more power to judges – not politicians. Image Credit: Aron Van de Pol / Unsplash

Some critics claim it has given more power to judges – not politicians. Image Credit: Aron Van de Pol / Unsplash

Critics of the HRA have also highlighted the way it expanded the role of judges in interpreting legislation as proof of its democratic illegitimacy. These attacks on the HRA often miss the point – bringing the Human Rights Convention into UK law the gave British judges the power to interpret human rights in UK courts.

Parliament remained sovereign; judges could not strike down laws as they could in the United States. The Human Rights Court, far from dictating the law, engaged in a judicial dialogue with national courts, allowing for considerable divergence over how rights were implemented in different countries.

A Skewed Public Perception

An overblown narrative in newspapers? Image Credit: Roman Kraft / Unsplash

An overblown narrative in newspapers? Image Credit: Roman Kraft / Unsplash

It is clear from polling on the HRA that the constitutional case against it has had far less impact on public opinion than the perception that ‘undeserving’ claimants, such as immigrants, prisoner’s, terrorist suspects and welfare claimants are using the Act unfairly.

There was never a broader national conversation on the importance of fundamental rights

Some of this has been based on overblown newspaper coverage of certain high profile cases. But, this reaction has deeper roots. When the HRA was being drafted the then Home Secretary briefed that it was a ‘tidying-up’ exercise, there was never a broader national conversation about the importance of fundamental rights.

The 2012 Commission of a Bill of Rights Report noted that whilst the Act had broad support in some areas of the UK there were some deep-seated negative perceptions of human rights. This has been exploited by those hostile to the Act – for example in the Reilly case (where the Department of Work and Pensions acted unlawfully in its administration of a back to work scheme) some politicians blamed the courts for engaging in ‘rights inflation’ and newspapers attacked the claimants for using the HRA to stay on benefits.

These perceptions appear to have been cemented in 2007-2009 when there was a barrage of sensationalised reports about criminal and immigration cases using the HRA and both major political parties backed critical policy documents on human rights. With Brexit and the rise of anti-immigration sentiment the broader social and political context reinforced hostility to the Act. Although, as often pointed out in the pages of this blog, EU law and the Human Rights Court are two very different things the broader scepticism about supranational courts and the seeming lack of democratic control characterising anti-EU sentiment fed into the case against the HRA.

Stronger Political Foundations Are Needed

Theresa May has backtracked on plans to scrap the Act. Image Credit: Number 10 / Flickr

Theresa May has backtracked on plans to scrap the Act. Image Credit: Number 10 / Flickr

Although the Human Rights Act’s defenders can often point to the popularity of certain rights, such as the right to a fair trial, the process often involves tolerating a set of trade-offs about what rights are and whom they should protect.

Earlier this year the government abandoned plans to repeal the HRA and replace it with a new Bill of Rights -not because the case against the Act had in any way diminished but because of the legislative difficulty in doing so whilst also leaving the EU.

Therefore whilst the HRA will have a few more anniversaries to come it remains more tolerated than revered. Weak as some of the arguments against the HRA may be from a legal standpoint, they gain the traction they do in the popular imagination because of the Act’s fragile political foundations.

This is a summary of the research presented in Cowell (eds.) Critically Examining the Case Against the 1998 Human Rights Act which has just been published by Routledge