Karolina Piras was awarded ‘Best Human Rights Story’ by EachOther’s judges at the annual Student Publication Awards this month for this article which was first published by Sane Magazine. The views expressed in the article belong to the author and do not necessarily represent the views of EachOther.

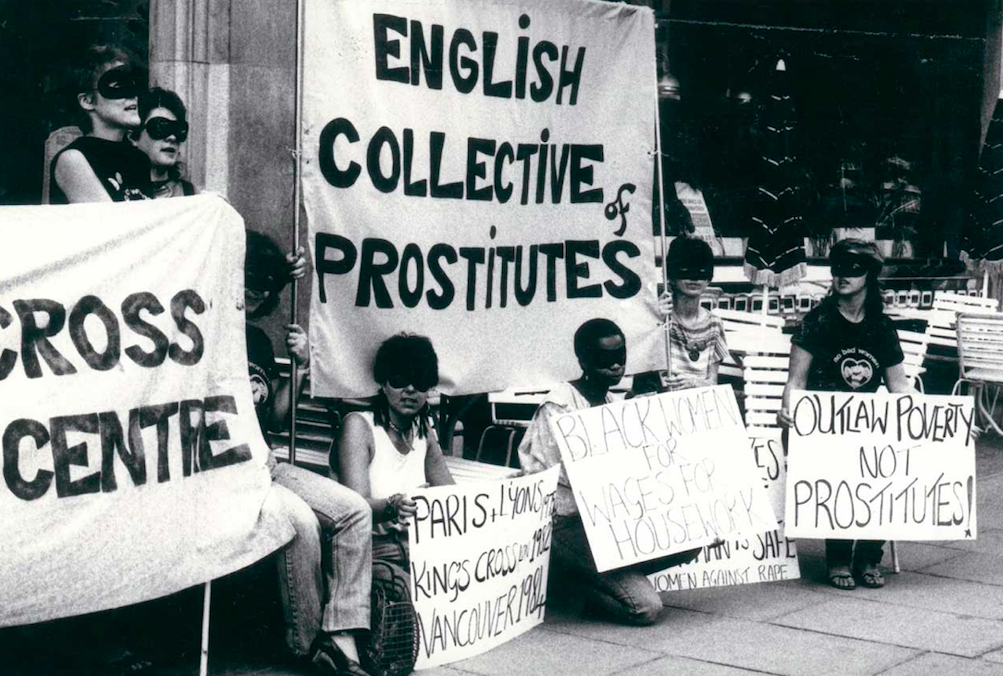

We had a chat with Carrie Mitchell, spokeswoman for the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), an organisation of sex workers with a national network, campaigning for the decriminalisation of prostitutes, sex workers’ rights and providing resources to enable people to get out of prostitution if they want to. “Most of all, we campaign for poverty, because women right now are experiencing real poverty.”

ECP has been around since 1975, quite a long time. “Sex work is about poverty, and about money,” stated Mitchell.

“Mostly for women, mostly mothers, mostly single mothers, to bring food on the table to their family, not only in this country but in other countries, especially a lot of migrant women supporting their families overseas.”

Another commitment of the organisation is to find lawyers and legal support and advice for women who are in need. “They may have been arrested or prosecuted, whether they were working outdoors or indoors.”

The laws are hurting sex workers and do not safeguard them, and, in the UK, rules and regulations are very hard on migrant sex workers.

Mitchell explains that health and safety laws for prostitutes and sex workers are basic and necessary now, especially considering the pandemic: “Health and safety are the basis on which we get organised here.”

Forgotten amid the Covid pandemic

One of the biggest issues, highlights Mitchell, was that during the pandemic sex workers were not entitled or had the chance to apply for benefits. They were left with nothing, despite the global situation that was going on. Some of them, couldn’t even access the most basic form of support.

Of course, due to the pandemic, sex workers stopped working and that meant they had absolutely no money.

Many of these women, migrant ones, were earning money through prostitution to support their family, so you can imagine the struggle of a woman finding herself without a penny to put food in their kids’ belly, not supported or helped by the government, and left without any entitlement for financial benefits. It’s like being an outcast.

“On the word of a single police officer, if they find you, you will get arrested straight away and you will have a record of a sexual offence. Once you have that, you can’t get another job,” explained the spokeswoman.

Mitchell mentioned the case of two sex workers’ living in a flat and working together when someone living on the same premises reported them to the police.

“At the moment of their arrest, they chucked their money away that they were about to send home to their families. The police simply took their money.”

For these reasons, the English Collective of Prostitutes has been playing a fundamental role in the fight for sex workers’ rights by actively getting involved in the political and legal side of the issue, by bringing petitions to the Crown Prosecution Service for wrongful convictions of sex workers, writing to MPs and more.

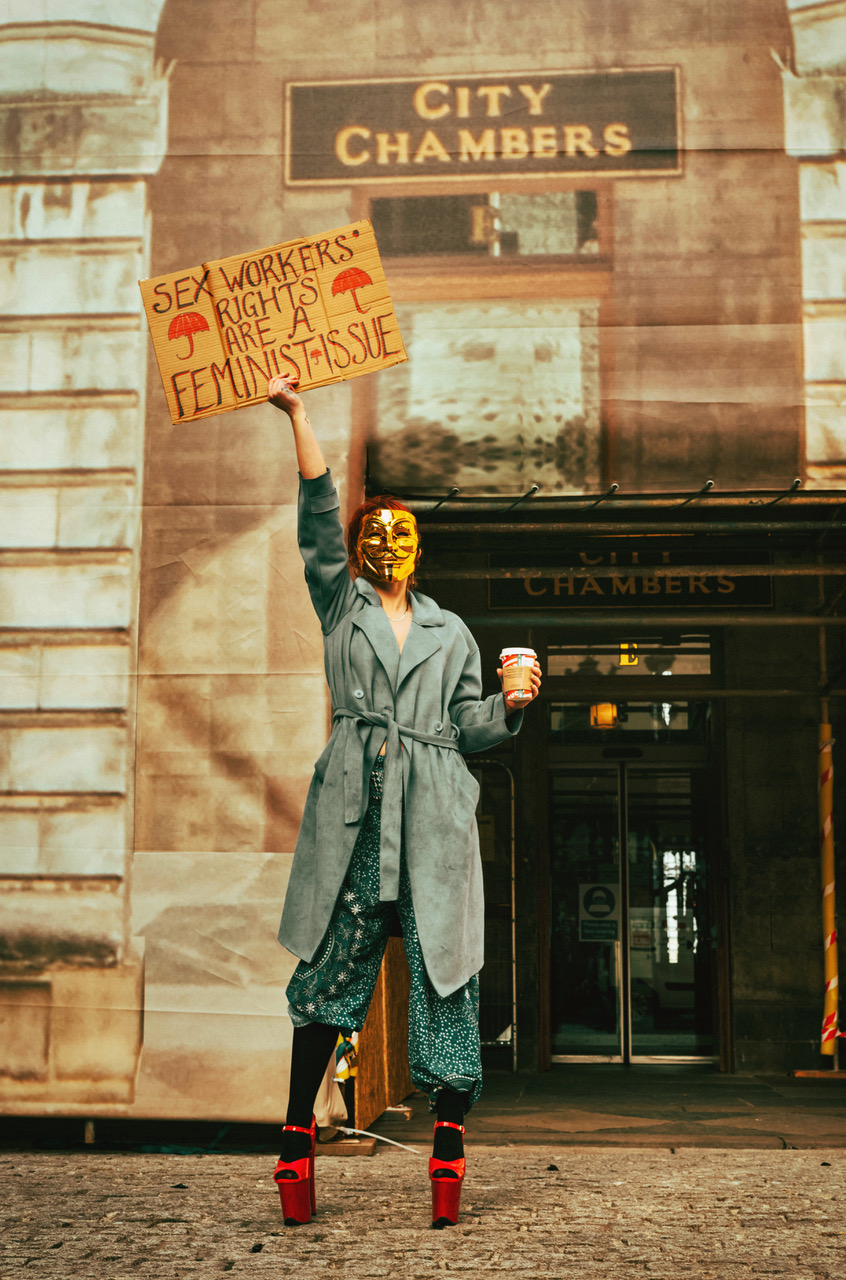

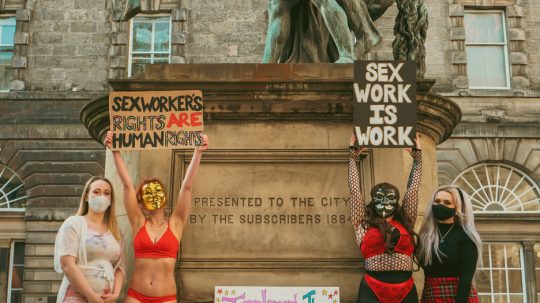

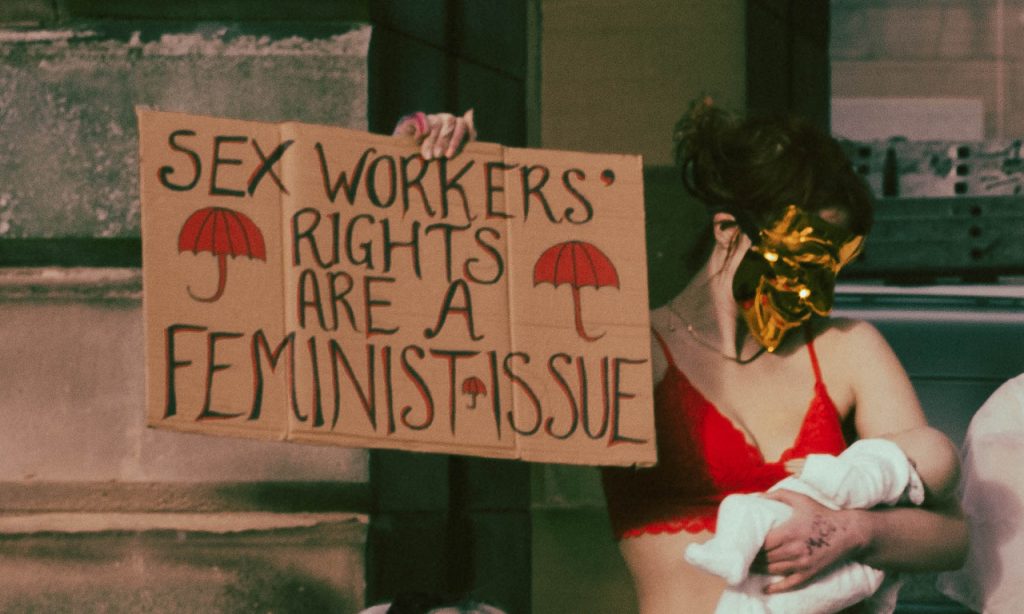

Credit: Mina Karenina (USW)

The legal situation in the UK

Diane Johnson, MP for Hull, was trying to bring in a bill called Bust The Business Model, that would criminalise sex workers and prostitutes. “But it does not do any of these things,” claimed Mitchell. “It doesn’t stop sex workers and they are still prosecuted by the police.”

Although it aims to bust the business model of sex trafficking and to put an end to exploitation, we need to shift our thinking to the fact that the criminalisation of sex workers, all over the world, has proved to be a failure, as it only bringing them underground and increasing the risk they are exposed to.

In addition, laws would become tighter on them and migrant sex workers, instead of progressing to safeguard their rights.

Both in the UK and other countries, as for example the US, the criminalisation of sex workers has doubled the violence and even ‘normalised’ violence as the sex worker is three times more likely to experience violence from the client whereas the trade is criminalised, data from The Guardian showed.

Mitchell actively calls for action on sex workers’ human rights: “Every single place where this kind of law has been introduced, violence has increased, stigma has increased, brought them even more underground.”

Mitchell stresses the number of sex workers that get killed every day, and how easy is to “get away with murder”, evidence of laws that do not take into consideration the human rights of sex workers and do not put safeguarding regulations in place.

Mitchell also referred to the known case of Romina Kalachi, 32, which was stabbed to death in Kilburn, in May 2017, one of the most recent sex workers to be murdered in the UK.

Despite this and the struggles that sex workers are still experiencing due to the pandemic, there is “a strong women movement against violence,” said Mitchell.

Lisa’s story: “I lived for months looking over my shoulder”

Lisa, a 26-year-old sex worker, who asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons, told us about an experience during the last year.

“As the pandemic restrictions were finally starting to ease, I got my business back on track and activated my accounts again. Instagram too, I did not use it for a while, so I activated one of my two accounts – the one for my job.”

“During a sunny Thursday like any other, I posted a story of the view from my flat, which looks very nice by the way. There is a particular detail in that view that someone apparently recognised.”

A man around his 40s, who saw Lisa’s Instagram story, signed up on the linked page she had in her bio. “That’s when the stalking started,” she said.

The man started following Lisa on alternate days, sending at first treats that she never replied to, moving to threats, anonymous phone calls, and tailing her to her home, gym and other places.

Lisa admitted she was hunted day and night by this man and had no idea what to do, as she was living alone and couldn’t always have friends coming over: “I lived for months looking over my shoulder. He would never stop. He would also book sessions with me on my page, to then cancel it.”

“The most hurting, disappointing thing is that when I went to the police station, I was simply rejected and told in a very subtle way that if I was a sex worker, I should have sort of expected that from clients.”

Lisa added: “I was also told that if nothing happened, there was as well nothing they could do to protect me.”

“It’s funny, because despite the fear you come forward to a system that has never protected you or cared about you, and they literally tell in your face: until you get murdered or you come bleeding to the station, we’re sorry but there’s nothing we can do”.