Amid the concerning increase in pupil expulsions in England and Wales, there have been calls to make our education system more compassionate. EachOther takes a closer look at what this means in practice and how British schools are making it a reality.

At south London’s Surrey Square Primary School, around 15% of children live in temporary accommodation and more than a third (36%) are eligible for free school meals (FSM). So when one pupil was repeatedly sent to co-headteacher Nicola Noble’s office for disruptive behaviour, having missed out on hours in the classroom, her response was not to simply issue harsher punishments.

In time it emerged the pupil was homeless and hungry, sleeping on a church floor with his family. The school provided them food bank vouchers, clothes, an inflatable mattress and eventually supported them to find more suitable housing. The boy’s behaviour was soon “transformed,” reducing his risk of being excluded.

Surrey Square, and its willingness to help pupils in ways that go beyond a school’s traditional remit, is included among a number of case studies in a 2020 report by the Royal Society for the Arts (RSA) on preventing exclusions.

“If something in your home life is affecting your ability to learn, then we need to do something about it,” the school’s family worker, Fiona Carrick-Davies, told the RSA.

Last year, schools in England issued 7,894 permanent exclusions – 60% higher than five years ago. The most common reason for exclusion was “persistent disruptive behaviour,” indicating that some pupils are consistently coming into conflict with the boundaries of their school’s rules, norms and expectations. Yet, according to England’s children commissioner, “there is no evidence behaviour patterns have changed”.

Multiple reports, by MPs and experts, have suggested that England’s surge is at least partly due to so-called ‘zero tolerance’ approaches to dealing with misbehaviour in some schools. In response, youth campaigners have called for “a more compassionate education system”.

In Scotland, there were three permanent exclusions last year. This summer, EachOther visited Glasgow’s St Roch’s secondary school while filming its forthcoming documentary ‘Excluded’.

In a video interview with headteacher Stephen Stone, it was apparent that compassion and an inclusive ethos – backed by Scottish government-funded programmes – were key to preventing exclusions at the school.

So, how do we ensure compassion – the “concern for the sufferings or misfortunes of others” – is at the heart of the education system?

Well, fortunately, a growing number of reports have produced numerous clear, evidence-based recommendations for reducing exclusions. These include studies by the RSA, Centre for Social Justice, the House of Commons Education Committee, The Children’s Commissioner, JUSTICE, and the Timpson Review. However it appears that action on these recommendations is slow.

EachOther looks at five ways British schools are preventing exclusions by adopting a more compassionate approach, as well as further steps that can be taken.

Ensuring behaviour policies do not discriminate against pupils

Compassion in schools is key to a good education. Credit: Unsplash

It is clearly important for schools to minimise disruptions to learning. But evidence suggests some mainstream schools have adopted overly-strict approaches leading to pupils being excluded for incidents that could be dealt with in school.

Young people from black, Asian and minority ethnicity communities interviewed by the RSA said they had been punished by their school for actions like “spudding” (or “fist bumping”). In 2019, experts warned that an east London academy’s rule of giving two-hour detentions to pupils who kiss their teeth risks “racial harassment” by unfairly targeting black students. Equivalent actions, such as “tutting,” carried no sanction.

Discipline procedure for a school in London.

How many more schools use similar?

How can schools possibly think this approach will ‘improve behaviour’? pic.twitter.com/zRIrGcsTma

— Dr Muna Abdi #JusticeForShukri (@Muna_Abdi_Phd) October 13, 2019

In 2018, MPs were also warned that a “zero-tolerance mindset” could lead schools to dismiss their duty to make reasonable adjustments for pupils with special educational needs or disabilities (SEND), such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) – which causes impulsiveness.

“We need reasonable adjustments,” James Daulby, director of literacy charity Driver Youth Trust said. “Zero tolerance, unfortunately, does not seem to … recognise reasonable adjustments, and they see them as excuses as opposed to reasons.”

Public bodies, such as schools, have a duty under the Equality Act 2010 not to harass or otherwise disadvantage people based on their protected characteristics, such as race and disability. The Act also places a duty on schools to make reasonable adjustments for people with disabilities.

Research by the children’s commissioner suggests that the strictest behaviour policies are present in a minority of schools. In London, 10% of schools were found to be responsible for 88% of exclusions in 2019.

Parliament’s education committee has urged the government to issue schools with guidance to ensure their behaviour policies are in line with international commitments on children’s rights.

The RSA recommends school leaders check their behaviour policies do not discriminate on grounds of gender, race, SEND or other protected characteristics, pointing to EqualiTeach as an organisation that can provide support.

Every pupil has a relationship of trust with at least one adult

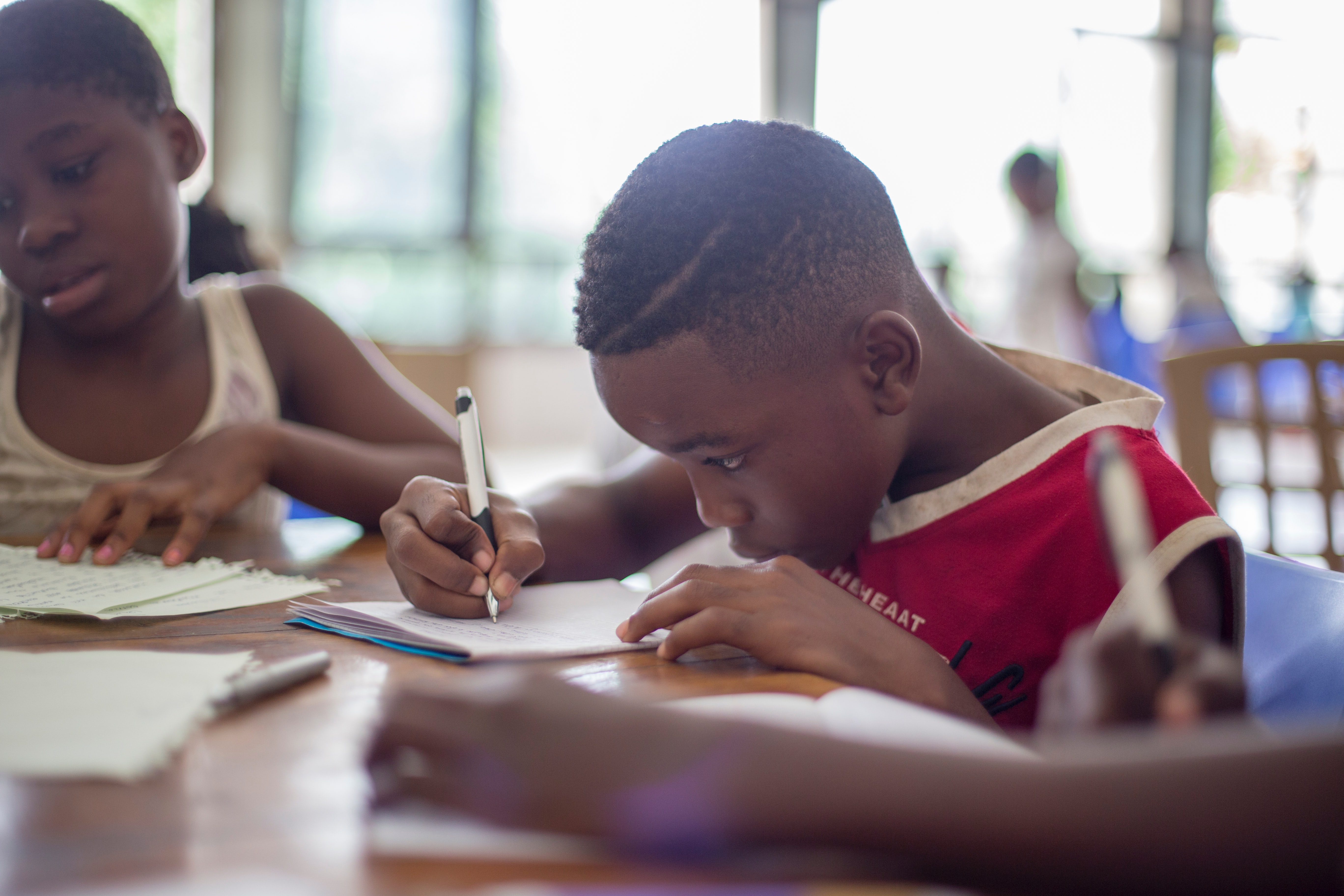

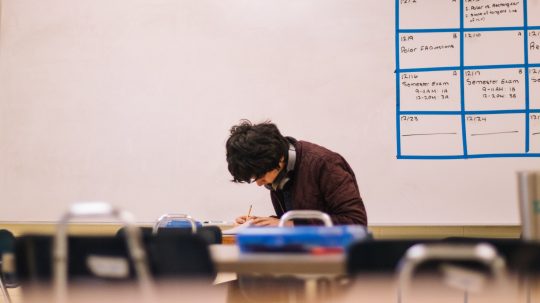

A teacher builds a trusted relationship with pupils. Credit: Motion Array / Pressmaster

The RSA has found that ensuring each child has a relationship of trust with at least one adult at school is a key condition for preventing exclusions.

This relationship enables the adult to become aware of problems in the child’s life which may lead to bad behaviour, and take action before any incidents happen which could lead to exclusion.

However, the report also outlines how England’s schools have faced funding cuts, leading to reductions in the number of support staff. Policy changes have also increased teachers’ workloads, leaving them less time to form relationships.

Nevertheless, amid these challenges, Leeds’ Carr Manor Community School is highlighted as taking an innovative approach to boosting pastoral care.

The school – which has a higher number of SEND pupils and children eligible for FSM than average – runs a coaching programme.

All adult staff, teaching and non-teaching, are ‘coaches’ for groups of around 10 students, who have check up meetings three times a week.

One student described her group as her “second family” while another explained that “you get to know one teacher really well… if there’s a problem you don’t want to speak to anyone at home about, you have that trust”.

The RSA recommends that the Department for Education should take steps to ensure that the importance of this pastoral work is recognised in how school staff progress in their careers.

Assessing children’s needs and providing additional support

More care needs to be given in assessing children’s needs. Credit: Pexels

Official figures show 17% of children excluded in England had a social, emotional or mental health (SEMH) need in the most recent year for which data is available.

Earlier this week campaigner and writer Emmanuel Onapa, in an article for EachOther, spoke of how he felt he was excluded from multiple schools on the count of not being able to articulate mental health issues he faced as a teenager.

Nevertheless, funding constraints have undermined teachers abilities to assess and meet all pupils needs. A 2018 survey conducted by the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) revealed that 94% of head teachers reported that they found it harder to resource the support required to meet the needs of pupils with SEND than they did two years ago.

Nevertheless, the RSA found examples of schools in England that had greatly reduced their exclusions by having mental health, social care, speech and language professionals on school grounds.

Among them is Reach Academy, in Feltham, west London, where almost half (44.9%) of its 900 students have been eligible for free school meals in the past six years.

The school has positioned itself as a hub for families in the local community to access support around antenatal care, mental health and adult education and employment.

By registering as a charity, the school has been able to access funding it was previously ineligible for.

In Scotland, Glasgow City Council has helped pupils through the Nurture programme, which has been credited with helping reduce exclusions in the city by more than 87% since 2006.

At St Roch’s, specially-trained staff support children whose home lives may be “very challenging” or who find school life challenging and could use extra help.

“They come in the morning, maybe have some breakfast, the chance to relax a wee bit before school, and to get themselves into a good frame of mind to learn and to have a positive frame of mind to learn for that day,” headteacher Stephen Stone told EachOther.

“[Or] it may be that there are some subjects that some pupils find extremely difficult or too much of a challenge … and we can withdraw them from certain subjects and give them extra support in certain other subjects where they will do well with that wee bit more support.”

An “enhanced transition programme” is also offered to those pupils who are struggling with the move from primary to secondary school.

This can include a series of visits where they come into school on an individual basis with a parent or carer – enabling them to tap into whichever part of the experience is worrying them, be it the size of the building or a particular subject.

Fostering an inclusive ethos

Some schools greatly reduced their exclusions by having specialists on the ground. Credit: Unsplash.

According to the RSA’s research, a child who is fully ‘included’ – given a sense of belonging and opportunities for success – is far less likely to behave in a way that would lead to an official exclusion from school.

To this end, an inclusive ethos, spearheaded by a committed leader, can contribute to preventing exclusions.

Conversely, measures to assess schools performance have created perverse incentives – which have resulted in pupils being informally excluded (or ‘off-rolled’) to improve performance in league tables.

The importance of an inclusive ethos was clear in our interview with St Roch’s headteacher Stephen Stone.

He explained how disruptive incidents at the school do happen – as they do in any school of almost 600 teenagers – but they “are few and far between”.

And the reason for this, he added, is largely down to school’s positive culture and atmosphere.

“Most schools have got a motto or a phrase that looks great … but it doesn’t actually have any impact on what happens in [the] school on a daily basis,” the head teacher added.

“Ours is short and simple, and it’s: ‘help others’.

“And that’s all about what we’re about as a school. And we are constantly reinforcing in our young people – the need that they have to help others.”

Experts have called for England’s education regulator Ofsted to ensure inclusion carries explicit weight in its school inspection gradings.

Working with families as partners in education

A mother and son stand by the sea front. Credit: Unsplash

The RSA also highlights that parental engagement in a child’s education is a contributor to success at school, and can also protect against exclusion.

By understanding a family’s situation, and any adversity they are facing, schools can intervene before a child is at risk of exclusion. Meanwhile, lower levels of parental support for learning are strongly associated with exclusion, which may be due to children becoming disengaged with their school.

Aforementioned funding cuts and resource constraints have limited many schools ability to foster relationships with families.

However, Pears Family School, an alternative provision in north London, is highlighted by the RSA as being innovative in this area.

For example, their ‘Parental Learning Hub’ brings together teachers, parents and therapists to discuss each child’s needs and offers training in areas like trauma and attachment.

Parents enthusiastically described the opportunity to share and problem solve as a group as a “support network”.

The school also invites parents to join classroom lessons on certain days of the week, allowing them to feel part of their child’s learning and progress.

Due it size and its specialism in catering to students with behavioural issues, the intensive support Pears’ offers “is difficult to achieve in a large mainstream setting”.

However, “staff and families stressed the importance of adopting elements of their approach, such as incorporating a focus on mental health into the curriculum and equipping staff and families alike to understand the impact of trauma on behaviour”.

___________

Excluded: EachOther’s forthcoming documentary

On 10 December 2020, Human Rights Day, EachOther will release ‘Excluded’, a documentary with a difference focussing exclusively on young people’s perspectives on school exclusions.

Young people have the right to education (The Human Rights Act, Article 2, Protocol 1). They also have a right to express themselves on issues that concern them, be listened to and taken seriously (UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 12).