Last week, the government revealed its proposals to reform the Human Rights Act (HRA) into a new Bill of Rights – a move which has sparked concern from civil society groups and lawyers.

Justice secretary Dominic Raab said that the “common sense” proposals would prevent abuses of the system and bolster “typically British rights like freedom of speech and trial by jury”. However, critics have warned that the reforms could weaken human rights protections in the UK.

The HRA establishes a legal obligation for the government and public bodies to uphold the human rights of everybody living in the UK, so that they are treated with respect and dignity.

Ultimately, there are fears that the government is seeking to replace the act with a new Bill of Rights

A statement signed by more than 60 civil society organisations branded changes to the HRA as “unnecessary and damaging”. Among the signatories were the British Institute of Human Rights (BIHR), Runnymede Trust, Amnesty, LGBT Foundation and Fawcett Society.

The government announcement follows the publication of the Independent Human Rights Act Review panel’s (IHRAR) long-awaited report on the HRA, spanning 580 pages.

A three-month consultation has been launched, seeking views on the government’s proposals.

What is the Human Rights Act?

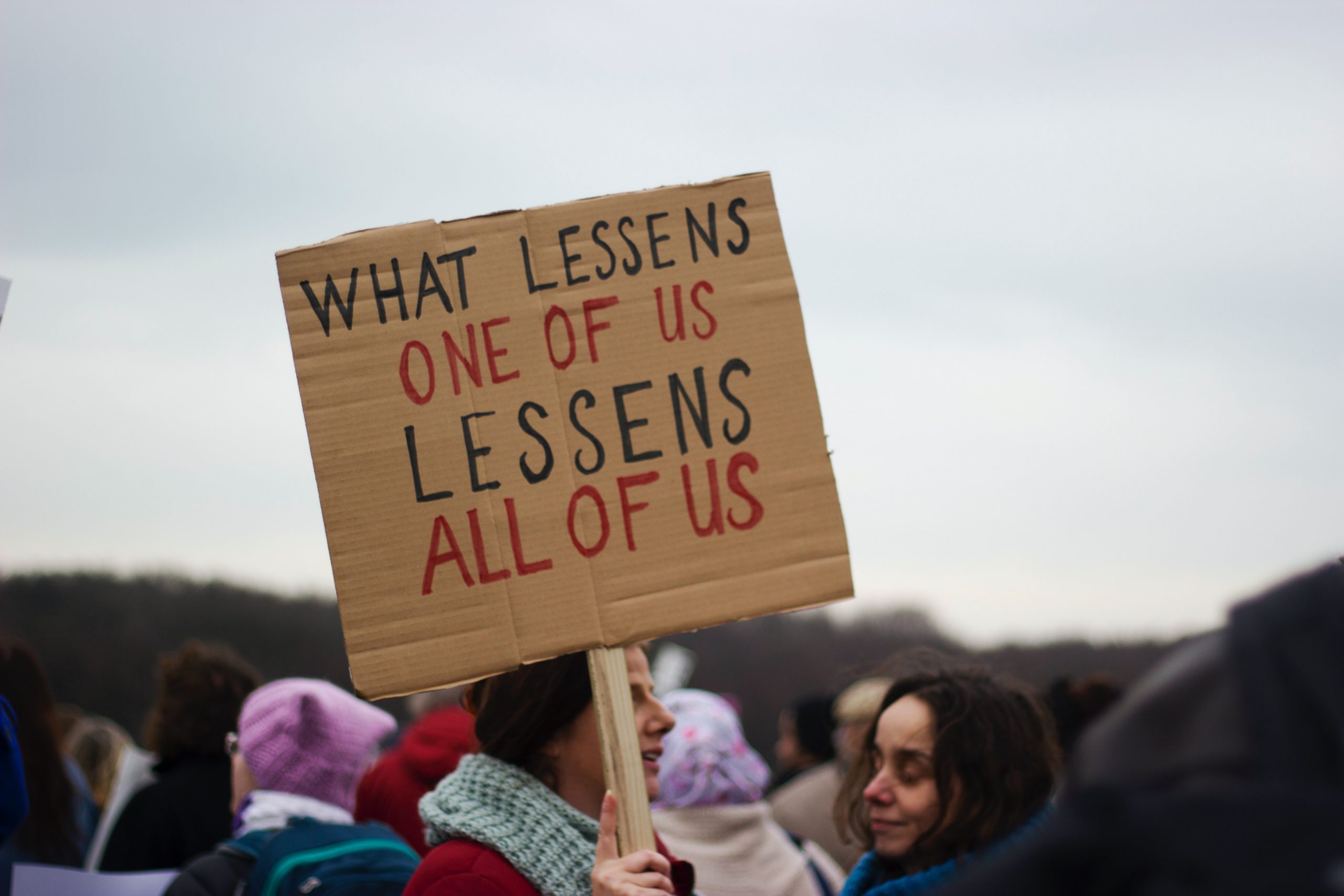

Credit: Andrea De Santis / Unsplasb

Passed in 1998, the HRA gives everybody living in the UK the ability to hold the government and public bodies to account if they fail to uphold their human rights.

If these human rights are breached, the Act means that people can take their case to a UK court and ask a judge to enforce them. A judge may also award them with compensation if their rights have been violated.

The HRA incorporates most of the rights enshrined under the European Convention on Human Rights, including the right to life, the prohibition of discrimination, freedom from torture, and the right to a fair trial.

Before the HRA came into force in 2000, people whose rights had been breached had to take their case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg – a time-consuming and expensive process.

Why is the Human Rights Act important?

Credit: Logan Weaver / Unsplash

The HRA has made an enormous difference to the lives of ordinary people by giving them the ability to stand up to those in power.

For the families of 96 victims of the Hillsborough disaster, the Act helped them to get a proper inquest into the circumstances surrounding the deaths of their loved ones.

The Act enabled two victims of rapist John Worboys to take the Metropolitan Police to court in 2014 for failing properly to investigate their rape claims. They won their case: the judge ruled that their human rights had been breached by the police, and that they were subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment under Article 3 of the Act.

“In 1995, when 18 year-old army recruit Cheryl James died from a gunshot wound to the face at Deepcut Barracks, witnesses weren’t called, medical records went uninspected and evidence was ignored in the initial police investigation,” said Martha Spurrier, director of Liberty. “The initial inquest into her death lasted less than one hour. It was only in 2011, when we invoked the Human Rights Act, that key evidence was finally produced and Cheryl’s family were able to get a proper inquest to get real justice and find out what really happened to their daughter.”

In 2015, the family of Cameron Mathieson, a disabled child, won a landmark appeal in the Supreme Court meaning that the families of sick and disabled children can keep receiving benefits regardless of how long they have to stay in hospital. Previously, the state cut off these benefits 84 days into a hospital stay, as had happened to Mathieson.

The HRA also helped Falklands veteran Joe Ousalice to get back his military medals earlier this year, without which he was unable to claim the pension earned from his service. He was stripped of the medals in 1993 after being forced out of the Royal Navy because of a ban on gay people serving in the army.

Other court rulings made using the protections in the HRA found that councils have a duty to provide adequate housing for disabled people, and resulted in the Ministry of Defence apologising to the families of 37 soldiers who died in Iraq and Afghanistan for failing to equip them properly.

What will the government’s proposals mean?

Credit: UK Government / Flickr

The government has announced plans to reform the HRA following the publication of the IHRAR’s report, which looked at how the legislation has worked over the past two decades.

However, human rights lawyers and campaigners are concerned, as these proposals go further than the recommendations of the report, which itself acknowledged that the “vast majority of submissions received by IHRAR spoke strongly in support of the HRA”.

Ultimately, there are fears that the government is seeking to replace the act with a new Bill of Rights which could dilute the protections enshrined in the current legislation.

As part of the announcement, the government opened a three-month consultation, seeking views on these reforms. The consultation will look at five areas, paraphrased below:

- Making sure our common law traditions and Parliamentary sovereignty are respected, and strengthening the role of the UK Supreme Court

- Providing a sharper focus on protecting fundamental rights

- Preventing the incremental expansion of rights without proper democratic oversight

- Emphasising the role responsibilities within the human rights framework

- Facilitating a dialogue with Strasbourg, while guaranteeing Parliament its proper role

What do the plan’s critics say?

There are a number of reasons why human rights campaigners are exercised. For example, the British Institute of Human Rights has said, among its concerns, that the first of the above five points could lead to UK courts only looking at previous decisions made in the UK, instead of taking into account relevant cases in the European Court of Human Rights. This, it says, could “narrow the interpretation and application of the HRA”.

Both the BIHR and Liberty have voiced concerns about the second of the government’s five points, which they say could introduce a new “permissions stage” for all human rights cases. This would mean people have to show they have faced “significant disadvantage” as a result of their human rights being breached, including gathering evidence ahead of a trial.

The government’s consultation on the reforms closes on 8 March 2022

“Evidence would need to be provided before a trial, meaning you would need to get evidence of the said abuse from your opponent, which in this case could be the British state,” added Spurrier. “That is a huge barrier to even getting your case heard.”

Another cause for alarm revolves around the third of the five points listed above, as the government has indicated it could change the law to restrict the human rights protections available to foreign criminals who are about to be deported. Migrant rights campaigners have argued that without the protections in the HRA, such as the right to respect for private and family life, this could lead to children growing up in the UK without their parents if they are deported.

“It’s important to note that, in the UK, we have a careful balance of power in place for a reason,” added Liberty’s Spurrier. “It’s to make sure when governments get things wrong – as they inevitably do – we have a way of holding them to account.

“This balance ensures that power is held in check and that nobody is above the law. The government’s long-held ambitions to overhaul the HRA puts all of that at threat, by tinkering with the details that will affect all of us.”

What happens next – and how can you take action?

Credit: Howard Lake / Flickr

It is important to note that no changes have been made to the HRA as yet: it still exists, the same as it has done since its enactment in 2000.

The government’s consultation on the reforms closes on 8 March 2022. You can fill it out here, so that your views on the importance of the Human Rights Act are included in the process. After this, the government will publish a report summarising the consultation results, alongside impact assessments on how the proposed changes could impact different groups of people, before drawing up a new bill.

For Liberty’s Spurrier, the government’s plans fundamentally threaten our human rights in this country. “While the language is about ‘correcting’ certain parts of the Act, we should be under no illusion – some of our most basic rights are at risk,” she explains. “This is, after all, a Government intent on making rules that only apply to us – not them”.