“Whether it’s being denied flexible working and having to work fewer hours as a result, or finding out you’re paid £3,000 less than a white man with the same job title and fewer responsibilities; it’s always crushing being treated worse than your peers.”

Those are the words of Sophia Moreau, who has experienced unequal pay repeatedly throughout her late teens and early 20s. The journalist and campaigner said that she has come to a “sad realisation” that, as a black woman, she cannot expect fair treatment.

Sophia Moreau, journalist and campaigner. Credit: The Equality Trust

“Coming to terms with how common and systematic unequal pay is for us has made me more prepared to challenge the individual battles as they arise,” she said. “It helps to remember that each time you refuse to accept an injustice, you’re making things easier for others who walk the same path.”

Moreau’s story is one of dozens gathered by charity the Equality Trust to mark the 50th anniversary of the Equal Pay Act – whose obligations are now contained with the Equality Act 2010.

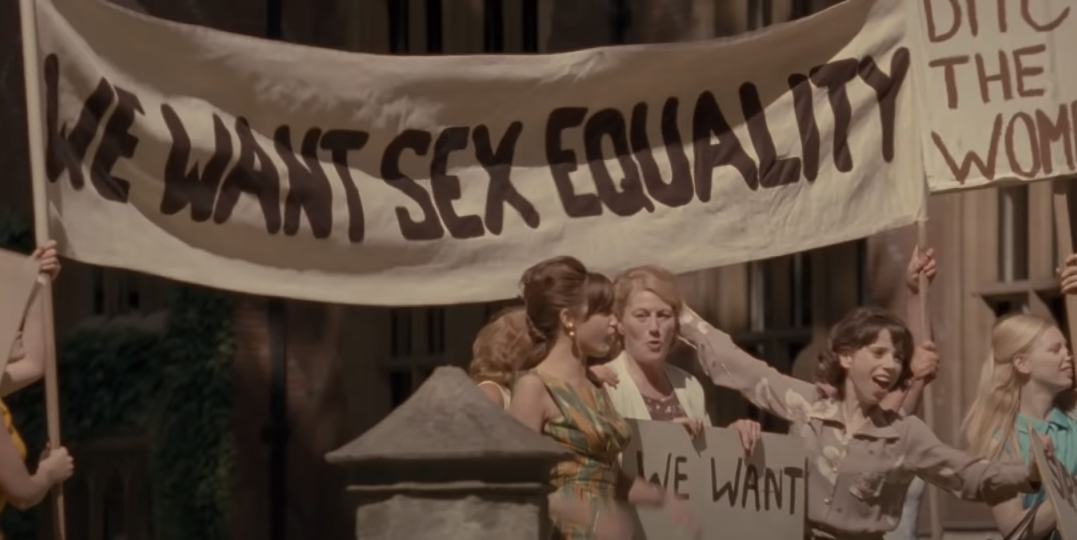

The Act was a landmark in labour relations and came off the back of three years of strike action instigated by the woman workers of the Ford factory in Dagenham, east London. These women, who were responsible for sewing car seat covers, laid down their tools on 7 June 1968 after a change in the company pay structure meant their male counterparts would be paid 15% more.

Five decades on, a new report published by the Equality Trust on Friday (29 May) reveals that there is still a “shocking level of complacency” among some of the world’s biggest companies over discrimination within their pay systems. The findings focus on gender pay disparity but also acknowledge that pay gaps affect people from minority ethnic backgrounds and people with disabilities.

Breaking down the data

The report reveals that there is a gender pay gap of more than 40% across the 10 worst FTSE 100 companies who provided data for the year to April 2019.

That means for every £1 men earned at these companies, women earned only 60p. At HSBC, the company with the biggest pay gap, women employees earned only 45p for every £1 their male counterparts did.

Across the UK, official figures show that the gender pay gap stood at 17.3% across all employees in 2019 – a fall from 17.8% the year before.

The gap drops to 8.9% among full-time employees, reflecting that fact there are more women working in part-time jobs which tends to be lower paid for a number of reasons.

The ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ gaps

The report identifies two main causes for the pay disparity – which it calls the “horizontal” and “vertical” gaps.

The horizontal gap refers to cases of men being paid more for doing work of equal value – a form of direct discrimination which was expressly outlawed by the Equal Pay Act.

All FTSE 100 companies who reported data in 2019 said that no horizontal pay gaps exist within their organisations. However, the report added that this claim is “often wholly unsupported by evidence in many cases”.

Analysis by law firm DLA Piper has revealed that England and Wales’ employment tribunals have received almost 29,000 unequal pay complaints a year on average since 2007.

The “vertical” gap refers to the “disproportionate failure” to appoint women to higher paid roles. The report said that this gap stems from numerous factors.

It can include instances of direct discrimination, such as decision-makers believing women or minorities are not good enough.

It can also include indirect discrimination, where employers fail to make a workplace accessible. Structural disadvantages people experience in wider society on the basis of their gender, ethnicity, disability or class also play a role.

At a time when it’s extremely clear that the roles women do are acutely undervalued, being paid less than men for the same work or work of equal value, adds insult to injury.

Dr Wanda Wyporska, the Equality Trust

Dr Wanda Wyporska, the Equality Trust’ executive director, said: “Fifty years after the passage of the Equal Pay Act 1970 and women are still fighting for equal pay.

“At a time when it’s extremely clear that the roles women do are acutely undervalued, being paid less than men for the same work or work of equal value, adds insult to injury.

“The Equality Trust is calling for pay transparency across organisations, as part of an end to pay discrimination, not just for women, but for all.”

The pay gap, poverty and inequality

An older woman smiles as she shares an embrace with another woman. Credit: Pexels / Andrea Piacquadio

Pay discrimination is “an important part” of income inequality, according to the Equality Trust report.

Research shows that countries with high income inequality “see higher levels of mental and physical ill health, violent crime and incarceration, drug and alcohol addiction, teenage pregnancy and obesity and lower levels of social mobility, educational attainment and trust”.

In the UK, as it is in most places around the world, poverty is gendered. About 20% of women in the UK live in poverty compared to 18% of men, according to the latest figures from Department for Work and Pensions statistics. The poverty rate rises to 23% for single female pensioners and to 45% for single parents, of whom 90% are women.

It is not just the gender pay gap that is causing disproportionately high poverty rates for women. A report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission found that women are disproportionately affected by recent tax and welfare reforms, losing on average £400 per year compared to a £30 loss by men. Universal credit, the flagship welfare reform, has been reported to be discriminatory by design for women.

What can be done?

The gender pay gap is not inevitable, there are steps that companies can take in order to end discrimination against women.

The Equality Trust has set out a series of actions that would help companies achieve real gender pay equality, which includes:

- Undertaking and publishing a measure of their horizontal pay gaps.

- Having an evidence-based action plan to address their failure to recruit and retain women in high value roles, overseen by the remuneration committee

- Eliminating those elements of their pay and reward structures defined as ‘high risk’ by the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

- Adopting a contractual policy of a ‘right to know’ so that women can ask for and receive details of the pay of potential comparators.

- Expanding the gender pay gap reporting requirement to companies with more than 100 employees and to include ethnicity and disability pay gaps.