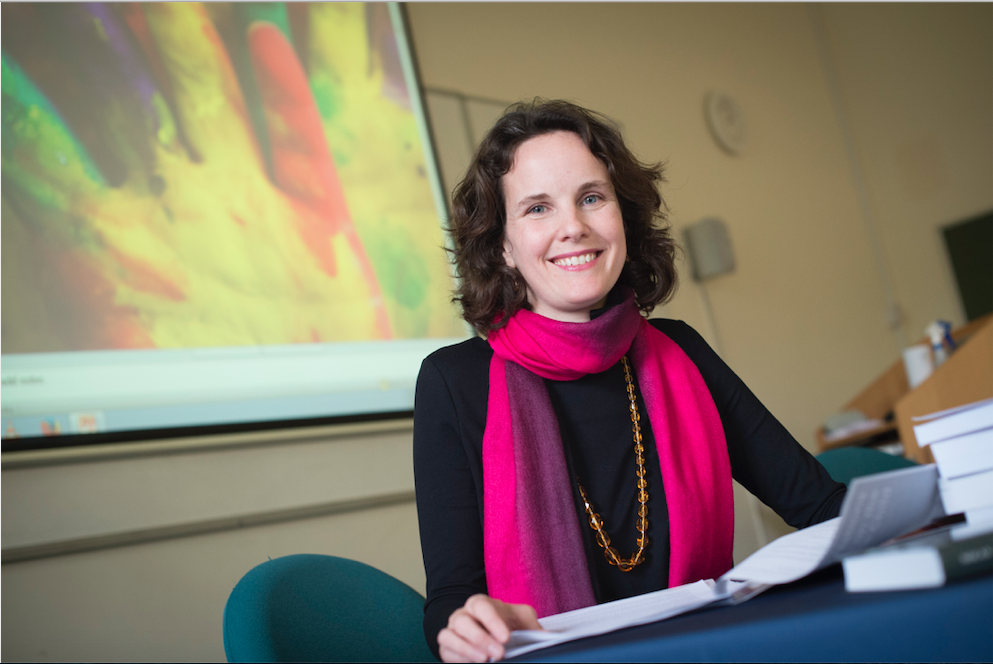

If your human rights were under threat, could you call on international law to defend them in a UK court? We speak to Professor Aoife Nolan, an expert on international law, to answer the question: are you protected by international law in UK courts?

Professor Aoife Nolan is an expert in international human rights law and a member of the Council of Europe’s European Committee of Social Rights. As part of EachOther’s week of coverage dedicated to the Human Rights Act, we sat down with Nolan to ask: are you protected by international law in UK courts? However, the UK’s adoption of international law is not as clear-cut a set of questions and answers as you might think. Nolan explained:

“You can rely on the provisions of the ECHR – the rights set out in the European Convention on Human Rights – because that has been domestically incorporated through the Human Rights Act. It has been brought into our domestic law as a result of an Act of Parliament.”

“That hasn’t happened for any of the UN human rights treaties. Bits and pieces of them are reflected in domestic law. But we’ve seen no wide-ranging incorporation of any of UN international human rights treaties in the way that has been the case with the ECHR.”

Credit: Aoife Nolan

Can we rely on international covenants and conventions in the UK then?

Nonetheless, international human rights law does play an important role for those living in the UK.

Nolan told us that international human rights law standards can be used to help offer support in defence of a right that already exists in domestic law:

“They play an important role. However, you can’t rely on them as the basis of a direct action before domestic courts. For instance, you can’t go to court and say ‘you violated my rights under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child’ and expect the court to act to remedy this. But you can say, this international human rights law standard is something that should be considered by the court because it provides the court with information that helps us understand what our domestic law seeks to do – or should be seeking to do.”

Credit: Micheal D Beckwith/Flickr

How does the UK adopt an international convention?

There are several stages that a state goes through to ‘sign up’ to an international convention. Those stages are: adopting, signing, and then ratifying the convention into domestic law.

The way it typically works in terms of international human rights law is that the UK, together with other states, will adopt a convention that is then open for signature and ratification.

The UN human rights treaties are a prime example of this: they are adopted by a specific number of UN states and then they are open for those states to sign up to them. However, when the UK signs up to a treaty, it has not committed to being bound by it under international law – and nor does it form part of domestic law in the UK.

“The UK has ratified all of the UN human rights treaties that we’re going to talk about now. And that’s significant because these treaties make specific articles legally binding on the UK in terms of international human rights law”.

Nolan explained that the UK signing a treaty is similar to it registering its interest in a treaty and is an indication that, although the UK is not currently bound by a convention, they may wish to be in the future:

“Signing an UN human rights treaty effectively means the UK or other state is saying ‘we’re not saying we’re bound by it now, but our signature expresses that we are willing to continue the treaty-making process’. So, you’ve got your adoption when the treaty comes into being, and then you’ve got your signature that says, ‘Yes – we are part of this treaty-making process’. That state is then on course to consider being bound by it.”

Credit: R/DV/RS/Flickr

States are not allowed just to turn their backs on conventions they have signed

During the process of signing up to a convention, because a state has registered its interest in it, it is not allowed to do anything that would undermine that international law. This means that if the UK has signed up to an international treaty, it cannot then simply turn its back on the convention.

Nolan explained that once a state has signed up to an international convention, it is not allowed to claim that is unaffected by it or to ignore its commitment to it:

“The interesting thing about a signature is, you don’t just sign up, and then get to say, well, actually, that doesn’t matter. A state can’t say ‘I’m completely unaffected by this treaty’.”

The primary reason for this is that when a state signs up to a convention it has an obligation to acknowledge its importance under the Vienna Convention: the treaty that lays down the rules about treaties – legal agreements between countries.

“When you sign up to a treaty, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969 makes clear that you have an obligation to refrain in good faith from any act that would defeat the object and purpose of the treaty – you must not do anything that will go against the spirit or the aims of it. So, by signing up, a state is already, to some degree, under international law, limiting its discretion in a particular area.”

The final stage of adopting an international convention is to ratify it. This is where a state makes clear that it consents to be bound by a treaty.

Credit: Sarah/Flickr

Can England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland sign up to different degrees?

In recent years, Scotland and Wales have extended legislation beyond Westminster in some areas when it comes to bringing international human rights standards into Scottish and Welsh law. We asked Nolan whether the UK and its constituent nations can sign up to international conventions to different extents. Nolan explained:

“Devolved nations cannot sign up to international conventions to a greater degree, because the power to sign up to international conventions is not something that is devolved. It is only the UK that can sign and become bound by international human rights treaties.”

Due to the UK being the sovereign nation-state, the devolved nations cannot sign up to international conventions to a lesser extent either. However, this does not mean they cannot create or change their domestic legislation to go above and beyond what the UK has decided is the standard.

Nolan explained that the Welsh Assembly has gone beyond what the UK decided it would adopt in regards to the rights of the child:

“In Wales, there’s a piece of legislation that requires Welsh Ministers to have due regard to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child when developing or reviewing legislation and policy. That legislation effectively results in greater protection for children’s rights under the CRC in Wales than is the case in England, for instance.”

Credit: Elliot Brown/Flickr

Some of the nations in the UK are going above and beyond the legislation

Nolan, who was previously a member of the Scottish First Minister’s Human Rights Leadership Advisory Group, which made recommendations on how Scotland can continue to lead by example in the field of human rights, said.

“In Scotland, we have recently seen an effort to fully incorporate the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into Scots law. While the bill was knocked back by the Supreme Court, because the scope of powers set out in it interfered with Westminster’s law-making powers in a way that was unacceptable, the Scottish Government has committed to ensuring that incorporation will still go ahead. That’s way beyond what you see happening even in Wales.”

“What we’re seeing in all of the developed regions – including Northern Ireland – are efforts to increase protection of UN human rights standards beyond the protection given to those rights by the Human Rights Act or other human rights-related legislation that’s been produced by Westminster.”

Some of the nations that make up the UK are taking positive steps by going above and beyond the UN human rights treaties that have been ratified in Westminster, demonstrating a commitment to do more to protect human rights in their own countries.

The government is currently running a public consultation on its proposed reforms to the UK’s Human Rights Act, which protects the rights of people living throughout the UK. There is still time to have your say in this consultation, which will close on 8 March 2022.

In the run-up to the end of that consultation period, we have dedicated this week to covering topics associated with the HRA, which is now at real risk. You can catch up with our coverage and find related resources on our HRA spotlight here.