Human rights are supposed to apply to all of us equally – yet three quarters of Black people in Britain feel theirs are less protected than their white counterparts. Racism lies at the root of this inequality, writes Nadine Batchelor-Hunt.

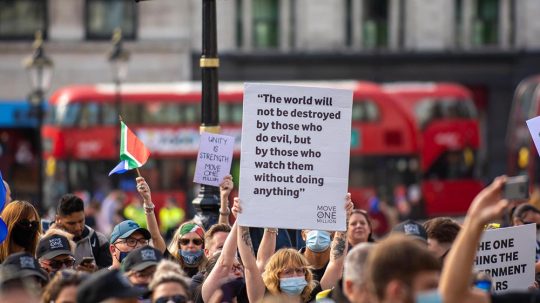

From our right to life, to our right to education, our human rights are universal and should be equally applied to all. But, as is clear from statistics – and from the catalysts for recent Black lives matter protests – Black people in the UK face disparities in many areas of life.

During the pandemic, the government has curtailed many rights – including our right to family life, and to assemble in groups – in the name of protecting human life from the coronavirus. In a national health crisis like a pandemic, forgoing some rights temporarily to protect others can be justified, when necessary and proportionate. However, as has become clear, Black people are dying disproportionately from Covid-19 compared to their white counterparts. This raises questions: are the lives of Black people truly being protected by these measures? Is Black people’s right to life being properly upheld? These health disparities are a manifestation of the socio-economic inequality that Black Britons have faced long before the pandemic.

These health disparities are a manifestation of the socio-economic inequality that Black Britons have faced long before the pandemic.

– Nadine Batchelor-Hunt

And Covid-19 isn’t the only frontier on which Black people are not enjoying the same right to life as their white counterparts. Black women are five times more likely to die in childbirth, and Black people make up a disproportionate number of deaths in police custody. All this demonstrates clearly how racism in society is interfering with Black people’s very basic right to life. And racism’s impact on Black Britons’ rights is not just limited to this sphere.

An Institute of Race Relations report published this month found that Black children are being unfairly excluded and criminalised by a “two-tier education system”. Not only that, but data shows that Black students are regularly under-estimated by their teachers, affecting their attainment. When I was 11 years old, I had a teacher tell me: “you work hard – considering you’re Black.” In a society where systemic racism pervades our educational institutions, is it possible that Black children have the same access to the right to education as their white counterparts?

Black people do not experience the same protection of their right to liberty as white people do, either. The police watchdog has launched an investigation into whether officers across England and Wales racially discriminate against Black people – who are disproportionately stopped and searched. Meanwhile, Black people are also disproportionately incarcerated. For all the comparisons many make with America when it comes to racism, the 2017 Lammy report found England and Wales has a greater disproportionality of Black people in prison than the US.

Systemic racism is present in British schools. Credit: Tamarcus Brown

In the justice system more broadly, Black people are given harsher sentences – and Black MPs like David Lammy say sentences should be reduced or reviewed to address the racial imbalances.

When it comes to our right to freedom from degrading treatment or torture, we know that the police are more likely to use stun guns on Black people rather than white people in similar situations. Earlier this year the harrowing footage showed Greater Manchester Police shoot an unarmed Black man with a Taser in front of his young child at a petrol station.

Indeed, the fact that the very basic human right of freedom from discrimination is not properly afforded to Black people in the UK renders us second-class citizens in the UK.

The fact that the very basic human rights of freedom from discrimination is not properly afforded to Black people in the UK renders us second class citizens in the UK.

Nadine Batchelor-Hunt

Until the racial disparities in contemporary British society are addressed, the human rights of white people will continue to be better protected, and treated as more valuable, than the rights of Black people.

Last month, the Joint Committee on Human Rights heard evidence gathered by ClearView Research which proposed a variety of recommendations to address the issue, including: better anti-racism laws, reform and review of the criminal justice system, and better education in school and in workplaces about equality and Black history. But questions remain over the efficacy of organisations set up to tackle racism in society – such as the Equality and Human Rights Commission, which does not have a single Black commissioner.

This month is Black History Month, and discussing and addressing these enduring inequalities in contemporary society must be part of it. In the words of James Baldwin: “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.” It is in that spirit that we must recognise that the battle for equal access to human rights is not over. For if Black lives are to matter, then Black human rights must matter, too.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.