From our ability to visit friends and family to our freedom to protest, ever-changing coronavirus curbs have affected our basic rights in countless ways.

Since the first national lockdown in March – scientists, politicians and legal experts have pointed out many lessons they say ought to be learned.

In September, MPs produced a report with 55 recommendations on how the government can ensure its handling of the pandemic respects our rights, with six relating specifically to lockdown regulations.

Last week human rights group Liberty urged Boris Johnson to adopt 17 measures it said would safeguard civil liberties and equality ahead of the new national restrictions that came into effect last Thursday.

As we enter our second lockdown, we draw out five key human rights lessons we can learn from the first, as identified in these reports and our previous coverage.

Restrictions and exemptions must be clear

Credit: Unsplash

A vast swathe of previously normal activities have been made illegal under the ever-changing coronavirus restrictions.

One of our basic rights – protected by Article 7 of the Human Rights Act – is that we should not be punished for an action that wasn’t a crime at the time you committed it.

This right requires public authorities to explain laws clearly enough for us to know what is and isn’t criminal behaviour.

In September, Parliament’s human rights committee warned that complexity and ambiguity in relation to what is law and what is guidance for the public – which tends to be stricter but is not legally enforceable – threatens to undermine Article 7.

In a letter to the PM last week, Liberty recommended that “communications by public authorities should accurately distinguish between law and guidance, and come from reliable and accessible sources, not via anonymous sources or paywalled publications.”

It added: “public authorities should maintain proactive and accessible communication of all exemptions, both to the public, and to authorities with enforcement powers.”

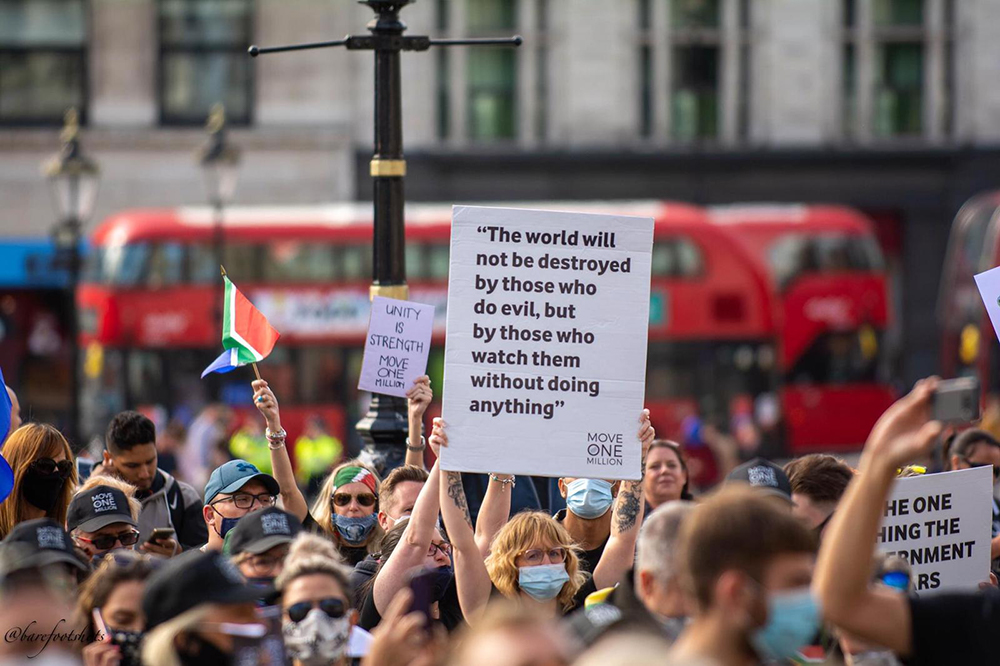

Protest is no longer explicitly included among the non-exhaustive list of reasonable excuses in the latest Regulations. Credit: Lucas Janse van Vuuren

So, what about now?

The second lockdown came into effect last Thursday after MPs voted to introduce the Health Protections (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (No. 4) Regulations 2020, which we’ll refer to going forward as the Regulations.

News of this lockdown was first made public on 31 October following an anonymous leak to the press. Further details appeared on reporters’ Twitter feeds in dribs and drabs until the prime minister held a press conference in Downing Street the following evening.

Meanwhile, the government’s (non-legally enforceable) guidance for the public to help curb the spread of the coronavirus was published on 31 October.

Between 1 and 3 November, this guidance was updated five times, according to barrister Charles Holland, including increasing the age of those defined as “clinically extremely vulnerable” from 60 to 70.

Ambiguity remains around at least a few aspects of the latest Regulations, lawyers have highlighted.

One area is in relation to protest, which is no longer included among the non-exhaustive list of exemptions from restrictions on gatherings. Previous iterations of the Regulations allowed for demonstrations to take place with additional conditions to mitigate the spread of the virus.

While protest has not been banned, some fear the removal of the exemption will render large-scale lawful protest almost impossible. Although others think it would probably be permitted.

Contrastingly, the Regulations do contain explicit exceptions for socially distanced Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday gatherings.

A Home Office spokesperson told the Guardian: “People must follow the rules on meeting with others, which apply to all gatherings and therefore protests too.”

To aid the public’s understanding of these new rules, human rights lawyer Adam Wagner, the founder and chair of EachOther, has voluntarily made a video explainer:

Evidence must be transparent and restrictions scrutinised

The lockdown restrictions have been justified on grounds of helping to protect lives amid the pandemic.

Under Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the UK government and other public authorities have a legal obligation to take positive steps to protect people whose lives are at risk, including from Covid-19.

But, in doing so, many other rights have been curtailed. This includes the right to liberty (Article 5 of the ECHR), freedom of assembly (Article 11) and the right to education (Protocol 1, Article 2) and businesses owners’ right to enjoy their property peacefully (Article 1, Protocol 1).

All of these rights must be balanced with the right to life and can be lawfully interfered with on the grounds of protecting public health.

So long as government measures are necessary and proportionate to a legitimate aim (such as preventing the spread of a pandemic), interferences with the rights to assembly, education and movement can comply with human rights.

However, businesses, politicians and experts, among others, have accused the government of failing to provide evidence to show that some of its measures are necessary, proportionate or effective.

Last month a nightclub and hospitality union each took legal action against the government, calling on it to make public the evidence behind its 10pm curfew and three-tier restrictions system.

Prime minister Boris Johnson is under pressure to be more transparent. Credit: Number 10

So, what about now?

In a Downing Street press conference on 1 November, Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance presented a series of graphs to justify its second national lockdown – suggesting a possible peak of 4,000 deaths a day .

On Saturday, statistician David Speigelhalter told BBC’s Radio 4 today programme that the graphs did have some “validity” but needed to be taken with extreme caution as they “were out of date” by the time they were shown.

On Thursday the UK’s statistics watchdog told the government its “use of data has not always been supported by transparent information being provided in a timely manner” and warned this could undermine public confidence.

It recommended that where key decisions are justified by reference to statistics, the underlying data should be made available.

Planning ahead to prevent discrimination

Labour’s shadow women and equalities secretary Marsha de Cordova. Credit: YouTube

The virus and lockdown restrictions have clearly not affected everyone equally.

People from black, Asian and minority ethnicity (BAME) communities were both disproportionately affected by the virus and more likely to be fined by police for alleged breaches of coronavirus regulations.

Under the first lockdown, people with disabilities struggled to access essentials such as food and medicine amid panic buying.

Meanwhile children from lower socio-economic backgrounds faced struggles with home schooling due to lack of access to technology.

As England emerged from its first lockdown in July, the London-based international organisation the Equal Rights Trust told us these disparities suggested the government had not fully assessed the equality impact of many aspects of its response.

In July this year, following public pressure and threats of legal action, the government published its EIA into the Coronavirus Act four months after the law was introduced. This is the only one of the government’s many national responses – such as the furlough scheme and latest lockdown – for which it has produced an EIA, Labour says.

Last month Marsha de Cordova, the shadow women and equalities secretary, wrote to the Equality and Human Rights Commission urging it to investigate the government for breaching the Equality Act.

De Cordova said: “Equal opportunity does not mean treating everybody the same and seeing who sinks and who swims. The government must take proactive steps to prevent the disproportionate impact of Covid on Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) and disabled people.

“Its failure to do so is negligent, discriminatory and unlawful, and ministers must be held to account.”

A spokesperson from the government’s equality hub told the Guardian at the time: “Throughout the pandemic the measures introduced by this government have been designed to protect and support everyone, including our most vulnerable.”

So, what about now?

No EIA appears to have been published on the latest lockdown measures.

Parents of people with severe disabilities spoke of feeling like an afterthought after an initial version of the lockdown guidance stated that people would only be allowed to meet with one other person from another household outside.

The original plans counted a parent and a baby or a child with severe disabilities as two people – which would have meant them being unable to meet up with anyone else while caring for their child.

The government agreed to change its new lockdown rules and on Sunday afternoon, health minister Nadine Dorries announced children under school age with their parents, and children and adults with severe disabilities, would not count towards the limit on two people meeting outside.

People must be enabled to comply

A mum works from home while looking after a baby. Credit: Unsplash.

For people to comply with the coronavirus restrictions and guidance, it is also important they have enough income to survive and safe housing.

During the first lockdown the government took several unprecedented socio-economic steps.

This included placing more than 15,000 rough sleepers in hotels under its “everyone in” policy, which is estimated to have saved 266 lives.

It has introduced job support schemes to protect the incomes of millions of people who are unable to work.

These packages of support have been welcomed, but campaigners have highlighted that many are still falling through the cracks.

For instance, in September we reported on how migrant workers are being forced to choose between dying on the job and destitution due to Home Office’s no recourse to public funds policy.

Liberty has called for NRPF conditions to be lifted “for the duration of the restrictions to ensure that everyone has access to the social safety net, and to minimise the need for people to continue potentially unsafe and exploitative work”.

The Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government has announced additional £15m of funding for local authorities to help rough sleepers amid the lockdown and winter and placed a pause on evictions. However campaigners say a relaunch of the “everyone in” scheme is needed.

Fair enforcement and a right to appeal

Credit: Pixabay.

Official figures show that more than 20,200 fixed penalty notices (FPNs, also known as fines), had been handed out in England and Wales under coronavirus regulations between 27 March and 19 October.

Of these at least 62 carried a £10,000 penalty for breaching a ban on gatherings of more than thirty people, which included unlicensed music events, protests and private parties.

In September, parliament’s human rights committee said it was “unacceptable” that so many people were being fined under circumstances where:

- There is evidence police do not fully understand their powers

- Lockdown regulations have contained unclear or ambiguous language

- A significant percentage of prosecutions were shown to be wrongly charged

- There is no realistic way to review or appeal

“This will invariably lead to injustice as members of the public who have been unfairly targeted with an FPN have no means of redress and police will know that their actions are unlikely to be scrutinised,” the committee said in its report.

The committee urged the government to introduce a means of challenging FPNs by way of administrative review or appeal.

“We have worked extremely closely with the police throughout the pandemic and our dedicated police officers have gone above and beyond – keeping the public safe through engaging, explaining, encouraging, and enforcing only as a last resort,” a Government spokesperson told EachOther at the time.

“Both Houses have opportunities to scrutinise and debate all regulations, which must be approved within 28 days to remain in force. This is the same way all lockdown regulations have been made.”