Pat Kenny hit “rock bottom” in 2011 when he was sectioned under the Mental Health Act. Nine years on, he now works in a hospital supporting others like him to turn their lives around.

As a middle-aged man from a less well-off background, Kenny is a part of the section of UK society considered most at risk of suicide, according to a report published by prevention charity Samaritans in April.

The 51-year-old is backing calls for the government to take urgent action to protect this potential group of “hidden victims” of the Covid-19 pandemic, as lockdown measures amplify issues of loneliness, financial pressures and uncertainty about the future.

Samaritans’ report found that less-affluent, middle-aged men often had to reach a crisis point – where they presented a risk to themselves or others – before they were offered support.

Earlier opportunities to help before getting to that stage – such as when coming into contact with health professionals, local authorities, the criminal justice system or a job centre – are often “missed”.

Among a number of recommendations the report points towards is:

- increasing funding for suicide prevention schemes targeted at less well-off, middle-aged men and to properly evaluate their impact

- offering at-risk men a way to contribute to these schemes, such as through co-running support sessions developed and run by their communities

- avoiding framing services around “help-seeking” – which can imply there is something “wrong” with men and which can create stigma

‘I just snapped’

Kenny’s journey highlights the “vacuum of responsibility” that, according to the Samaritans research, currently exists in the support available for at risk men before they reach crisis point.

Back in 2011, Kenny was unemployed and homeless in London. His local authority had placed him in a hostel where he would be woken up in the middle of the night by another resident searching for drugs.

He felt unable to speak to friends and family about his mental health, which had deteriorated rapidly. “There was the taboo around mental health,” he said. “You’ve gone so far through [life] keeping it bottled up that, that was the way to do it.”

He added: “A lot of it was pride … there was a lot of people who did not know the entire time I was homeless.”

One night, Kenny hit breaking point. “I just snapped,” he said over the phone. He had an episode, during which he self-harmed, and the police were called, where they issued him with a Section 136 under the Mental Health Act. This is a legal clause that allows police to detain a person, where they need “care or control”, and take them to a place of safety. During the incident, Kenny was tasered twice by police as he was holding a razor blade to his throat.

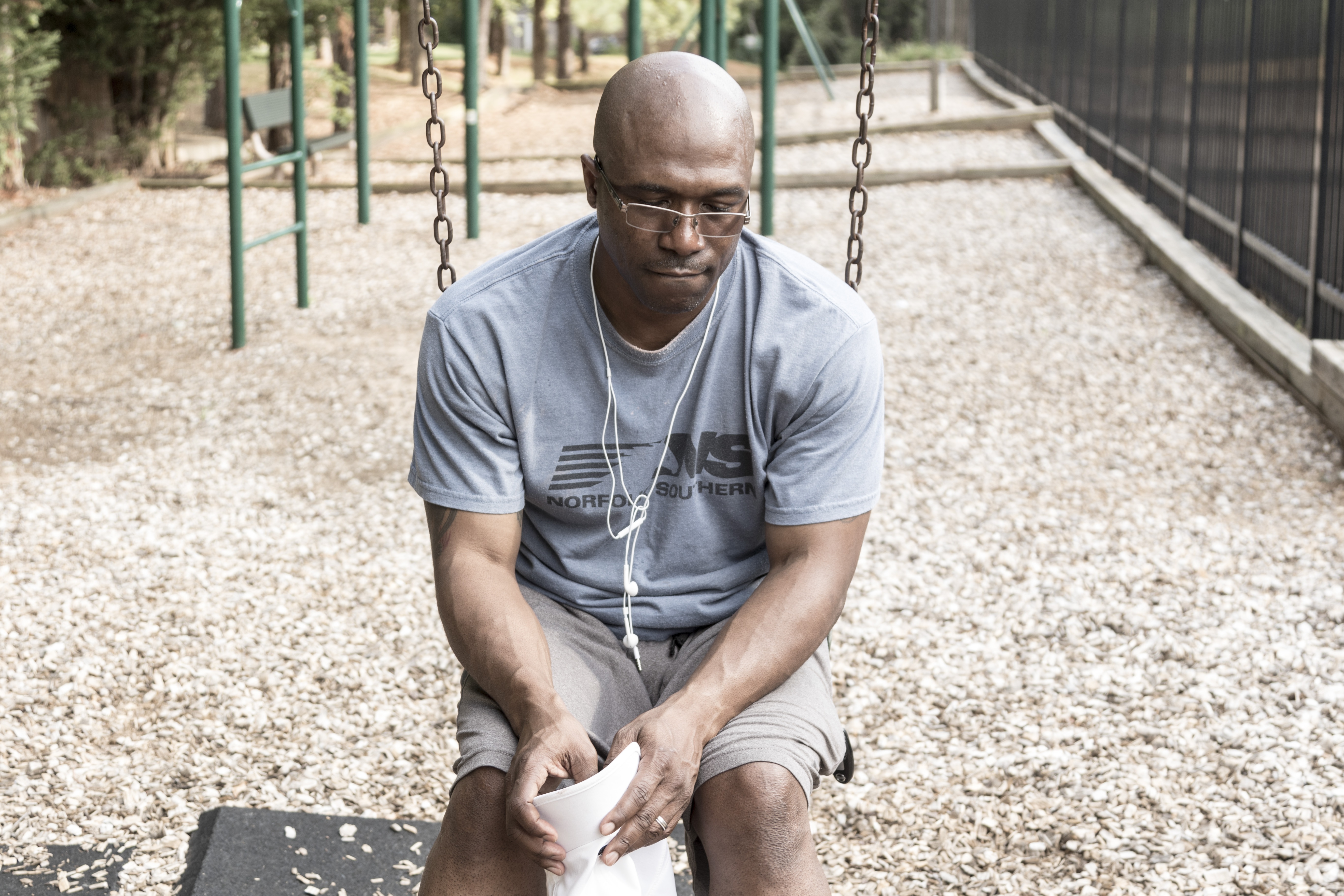

Kenny now works at North Middlesex University Hospital. (Flickr / Tom Page)

Kenny has since turned his life around. After being sectioned, he was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and given talking therapies alongside medication. He was also supported by mental health charities including Mind. Kenny began working in the mental health sector, helping others by sharing his story, at one point including a role at New Scotland Yard.

Kenny is now a peer support worker with the psychiatric liaison team at North Middlesex University Hospital. He treats patients who, like him, have been issued with a Section 136.

“I do my best to encourage [patients] to engage, I give them the benefit of my lived experience,” Kenny said. “Obviously, I will tailor it to the individual I’m talking to, because I don’t want to risk triggering them.”

These men are feeling worthless, they are feeling like a burden and feeling that their needs are perhaps not important compared to a physical health crisis

Jane Boland, centre manager at James’ Place

Jane Boland, centre manager at suicide prevention charity James’ Place, warned that the mental health issues facing men aged 45 to 65 is being “amplified by the pandemic”. She stressed that the government needs to treat male mental health as “a priority” during and after the coronavirus pandemic.

“Our concern is all those thoughts and feelings that come alongside feeling suicidal: these men are feeling worthless, they are feeling like a burden and feeling that their needs are perhaps not important compared to a physical health crisis,” she explained. She highlighted that periods of global uncertainty have often led to increase in suicides.

“Probably, in view of the Covid-19 crisis, more money needs to be put aside to prevent this crisis from having an impact on suicide deaths,” added Boland. EachOther has contacted the Department of Health and Social Care, and Public Health England for comment.

Alongside the Samaritans’ helpline, Boland said men can access help by calling CALM‘s support line and through initiatives like The Lions Barber Collective and the UK Men’s Sheds Association. She also recommended that those who are struggling with their mental health should book an appointment with their GP, who will put them in touch with the appropriate support services.

Men three times more likely to die

In the UK, men are three times more likely to die by suicide than women. The reasons for this appear to be numerous, complex and sometimes interlinked. According to the Samaritans’ report, some factors that can lead to an increased risk of suicide for middle-aged men include the breakdown of a relationship, social disconnection, and cultural stereotypes of ‘how to be a man’.

A 2016 study by the Mental Health Foundation found that men are less likely than women to seek help if they have mental health problems, and are less likely to confide in friends and family. Government figures show that men are more likely to be treated for drug or alcohol abuse than women, with research showing that alcohol can increase the risk of suicide by up to eight times.

Natalie Creary of Black Thrive, an initiative set up to improve the mental health of black communities in Lambeth, says that mental health problems affecting black people may be “exacerbated” due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Mental health inequality is generally linked to the social determinants of health such as employment, housing and education, she said.

She added: “If you’re from a black background – obviously not all black people are disadvantaged – you’re more likely to experience stresses in all of those other spheres of your life. When you think about it in the context of Covid-19 … they’re probably disproportionately impacted.”

Official figures show that black people are more than four times more likely than white people to die with Covid-19. While young black men are more likely to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act for complex reasons including stigma, cultural barriers and systematic discrimination, according to charity Mind.

Evidence has shown that black men are more likely to be diagnosed with severe mental health problems. Credit: PxHere

Urgent investment needed

Earlier this month, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a call, urging countries to “urgently increase investment” in support services “or risk a massive increase in mental health conditions in the coming months”.

Meanwhile, a United Nations policy brief on Covid-19 and mental health warned: “The long-term impact of the crisis on people’s mental health and in turn the mental health impact on society should not be overlooked.”

Kenny is now in a good place mentally and loves his job, but he worries for the mental health of others during the coronavirus crisis.

“Unfortunately, our hands are completely tied with the pandemic,” he said. “It’s a tough question: what can we do better?”

With peer support teams working from home under lockdown, Kenny added that mental health services are under even more pressure than they were before the pandemic.

He said that “absolutely, without a shadow of a doubt” the government needs to urgently inject more funding into mental health services, highlighting the drastic cuts in hospital beds for mental health patients in recent years .

“Even before this, we needed it,” he explained. “So now, more than ever, it’s needed.”

If you are in the UK and are having suicidal thoughts, suffering from anxiety or depression, or just want to talk, you can call the Samaritans helpline on 116 123. If you are in the US, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Line on 1-800-273-8255.