Some people talk about the European Convention of Human Rights as if it was imposed on the unwilling British by our continental neighbours, but the reality may surprise you.

Europe united by democracy and human rights? So whose idea was that?

The European Convention on Human Rights came into effect on 3 September 1953.

In the early 1940s, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill raised the idea of a ‘Council of Europe’. In the wake of World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust, the idea behind the Council of Europe was to set up an international organisation to promote democracy, the rule of law and human rights.

The Council was established by ten states, including the United Kingdom, on 5 May 1949. On 12 August 1949, Churchill said:

“The dangers threatening us are great but great too is our strength, and there is no reason why we should not succeed in… establishing the structure of this united Europe whose moral concepts will be able to win the respect and recognition of mankind…”

The Council of Europe set to work creating a human rights convention. Again, Churchill was an advocate; he proclaimed:

“In the centre of our movement stands the idea of a Charter of Human Rights, guarded by freedom and sustained by law.”

That ‘Charter of Human Rights’ of which Churchill spoke was named the European Convention on Human Rights.

Who wrote the Convention?

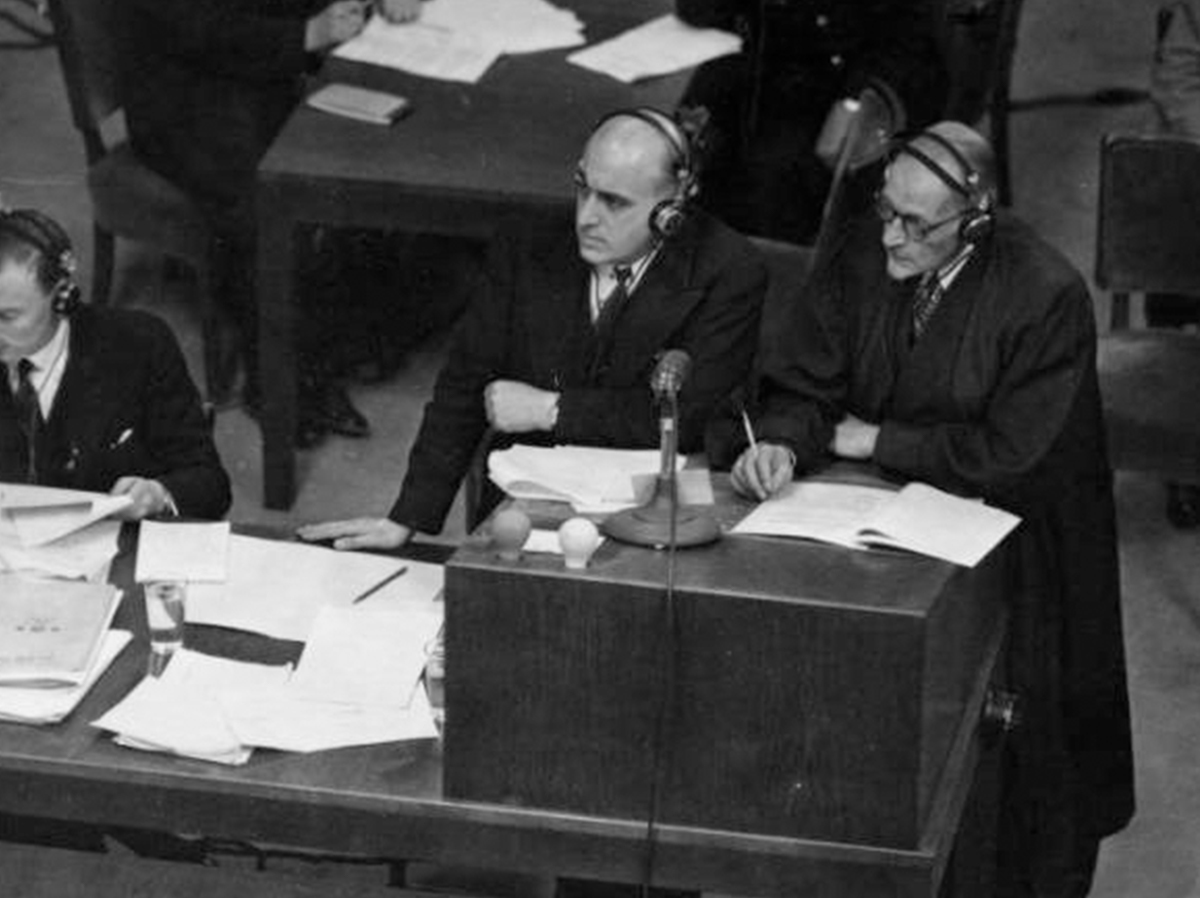

David Maxwell Fyfe prosecuted Nazis for war crimes during the Nuremburg trials. Credit: US Federal Image

One of the key writers of the European Convention on Human Rights was British Conservative MP and lawyer David Maxwell-Fyfe. Maxwell-Fyfe’s contribution to the Convention was so great that has been described as “the doctor who brought the child to birth”.

Before his leading role in drafting the Convention, Maxwell-Fyfe had been deputy British prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals. He was also involved in drafting the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Another important British player was Lord Layton: a Liberal Party politician, editor and newspaper proprietor. Layton was Vice-President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Others with important roles in getting the Convention into shape included Samuel Hoare (Home Office under-secretary), Ernest Bevin (UK Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs) and Harold MacMillan (a British Conservative politician and statesman who went on to serve as Prime Minister).

How was the Convention written?

Maxwell-Fyfe and other international lawyers started preparatory work on the Convention and a special section of the Council of Europe was created to produce a first draft. That draft was a simple list of rights which could be enforced by a European Court of Human Rights (which came later in 1958).

The draft was accepted, with modifications, by the Consultative Assembly and referred to the Committee of Ministers, who appointed legal experts to do the technical work. In February and March 1950, the experts struggled to agree and so they produced two versions of the Convention.

The Convention Debates

There were some pretty fierce debates about the content of the Convention during its drafting. One debate centred on whether the rights should just be listed or fully defined. The UK argued strongly in favour of definition. British politician Samuel Hoare worked to ensure that the rights were precisely defined.

A second major disagreement was about whether the rights should be legally enforceable. On this, British draftsman Maxwell-Fyfe said:

“We cannot let the matter rest at a declaration of moral principles and pious aspirations, excellent though the latter may be. There must be a binding convention, and we have given you a practical and workable method of bringing this about.”

The UK government also wanted to limit individuals’ ability to go to the European Court of Human Rights to complain about rights violations. Eventually it was agreed that states could decide whether or not give individuals the right to complain to the Court and whether or not to accept the Court’s jurisdiction. (These choices were set out in ‘optional clauses’ which states could choose to accept or not).

The first signature

In August 1950, a human rights sub-committee was appointed to finalise the text of the Convention and the finished draft was considered in September. The European Convention on Human Rights was signed in Rome on 4 November 1950. The UK was the first signatory to the Convention. The Convention entered into force on 3 September 1953.

At first, only Ireland, Denmark and Sweden accepted the right of individuals to complain to the European Court of Human Rights. In November 1958, the argument over the optional clauses (giving the Court jurisdiction and individuals the right to ‘petition’ the Court) was re-introduced to the UK Parliament. Lord Layton stated: “the right of individual petition is perhaps the most fundamental”. Eventually, in 1966, the UK accepted the optional clauses. In 1998, Protocol 11 to the Convention made the right of individual petition compulsory.

An ideal of Europe united by democracy and human rights was championed by the #1 Greatest Briton. The great ‘Charter of Human Rights’ Churchill envisioned became known as the European Convention on Human Rights. It protects the right to life, to liberty and security of person, to free speech, to a fair trial, to free and fair elections and to freedom from torture, slavery and discrimination.

Know your rights. Celebrate them. Protect them. For more information:

- Subscribe for free to our email updates

- Read about the Convention in more detail here.

- The European Convention on Human Rights takes effect in the UK through the Human Rights Act – read more about the Act here.

- Take a look at the text of the Convention and the rights it protects.

Featured image: Pexels.com. Churchill image © Dave Strom, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic Licence. David Maxwell Fyfe image: public domain. Writing images: Unsplash.com. Typewriter image © Dennis Skley used under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic Licence.

This article was updated on 20 June as part of our regular review to make sure our content is up to date.